Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

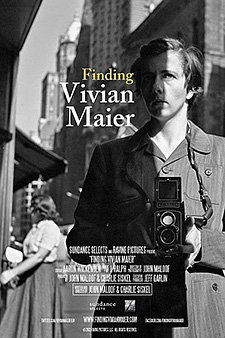

Finding Vivian Maier (2014)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Finding Vivian Maier” is the “Searching for Sugar Man” of photography. It’s about the artist who is discovered after the career or the life. It’s about resurrection and redemption: finally coming into the light after years in the neglected dark.Both movies are also mysteries.

The mystery of “Sugarman” is this: How did the singer/songwriter Rodriguez die in the early 1970s and why was he huge in South Africa and unknown in his native U.S.? The answers to these questions are intriguing. The mystery of “Vivian Maier” is this: Who was Vivian Maier, and why was she content to take tens of thousands of beautiful photographs and never show them to anyone?

The answers to these questions are less than satisfying.

Not a nice person

You know whose name I was surprised I didn’t hear during “Finding Vivian Maier”? Franz Kafka’s.

Kafka, private and reclusive, published only a few things in his lifetime but had written much, much more. On his deathbed, he instructed his friend Max Brod to burn the rest. Brod didn’t. He published. The rest is literary history.

Vivian Maier, private and reclusive, was born in 1926 and began work as a nanny in the 1950s because it allowed her the freedom to pursue her art: photography. She took pictures all the time but showed them to no one. Sometimes she didn’t even bother to get the film developed. After she died in poverty in 2009, some of her things were bought at an auction by real estate agent John Maloof, who saw value in it. He developed some of her photos and posted them to flickr. They took off. The rest is photography history.

Here’s another connection: Kafka once wrote, “A writer is not a nice person.”

That was one of the questions we batted about after the movie: Can you be a nice person and a great artist? Or even a crappy artist? Doesn’t art demand both empathy (to understand someone else’s life) and its lack (to use it for your art)? For the street photographer, how close to these strangers can I get? How much of them can I steal without their knowledge or permission? There’s a scene in the early 1960s in Highland Park, Ill., where one of the neighborhood kids is hit by a car. Everyone rushes around trying to help. Vivian? She’s taking pictures with her Rolleiflex.

The Rolleiflex helps in this regard. She can set the shot and take the picture without appearing to take the picture. She can look people in the eye as she steals from them.

For what it’s worth, I love her work. I love black-and-white street photography from bygone eras anyway and hers seems of a high standard. She’s got a good eye and a quick finger. She captures moments and lives. We see a lot of the photographs. But the doc, directed by both Maloof and Charlie Siskel (“Tosh.0,” producer on “Bowling for Columbine”), is mostly about Maloof’s search for her.

Initially, he knows nothing. He just has trunks of negatives and prints and undeveloped film and 16mm movies. He buys more of her things and lays them out before the camera like in a Wes Anderson movie: campaign buttons, for example. She was a pack rat. Later we learn she was a hoarder. And worse.

He discovers she was a nanny and find her former charges, and their friends, and the parents of their friends, who may have been her friend.

They describe her similarly: tall, domineering, to-the-point, political. She wore odd, heavy clothes and hats—like she was living in the 1920s rather than the 1960s—and walked with long strides and stiff arms. She had an odd French accent. There’s some debate about whether it was real or not. One man says yes; a linguist says no. Even we debated it afterwards. I assumed it was fake since she was born in New York, but my friends said no, it was real, since she lived half of her childhood in France with her French mother. We visit France, her mother’s village, Saint-Bonnet-en-Champsaur in the French Alps, and meet people there, and some part of the mystery is solved. A letter she wrote to a French developer about how she wanted him to print her work. She had high standards and wanted those standards met. This is a great, necessary revelation for Maloof, since he’s a nice person and is plagued by the doubt that Vivian wouldn’t have wanted her work exhibited the way he was doing. But here was proof. He could continue.

That’s hardly a revelation for us, though. We’re watching the doc, so we know Maloof continued with it, so getting a kind of posthumous permission isn’t news. Besides: permission? Did Vivian get the permission to take half the photos she took?

No, greater revelations comes in the final third, while interviewing her charges from 1968 to 1974. Apparently she became worse, and cruel. She force-fed one girl and hit her. She swung her around, then let her go. She brought her to the stockyards to watch animals being slaughtered. Somehow she kept her job for six years.

We lose the thread of her story in the ’70s and don’t pick it up again until the late ’90s. By then she’s homeless, and alone, and lonely. Some former charges—whom she didn’t abuse, apparently—pony up for a small apartment, where she lives until she dies in 2009. A few years later she’s an internationally acclaimed street photographer with exhibitions all over the world. Luck? Happenstance? Was she the one preventing her own success? Once she was out of the way, it came rather quickly.

Some day my Maloof will come

Question: do we get the wrong gerund in the title? Given the power, I would switch it with “Sugar Man”’s, since they actually find him. They interview him. We get a sense of who he is and who he was and why he did what he did. But Vivian? Do we find her? Not really. Too much of her remains unknown and unknowable. We’re left with questions. Why would she print nothing? Why would she show no one? Buddy Glass has a line in “Seymour: An Introduction,” “I always want to publish,” and that’s me, so I don’t get the opposite urge. But I admire it. Sort of.

I admire it for this reason. Besides being redemption songs, “Searching for Sugar Man” and “Finding Vivian Maier” are both wish-fulfillment fantasies for every would-be artist out there toiling in obscurity. It’s the “some day” wish. Some day they’ll know. Some day they’ll see. Some day my Maloof will come and the world will open its arms wide and take me in. And it’s an awful, awful wish.

—April 17, 2014

© 2014 Erik Lundegaard