Monday March 04, 2019

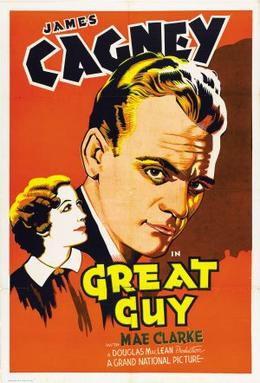

Movie Review: Great Guy (1936)

WARNING: SPOILERS

A few reasons why “Great Guy,” a mostly forgotten James Cagney film, is notable.

Its protagonist, Johnny Cave (Cagney), works for the Bureau of Weights and Measures. Think on that for a moment. What would the modern equivalent be? A hero from, say, the Food Safety and Inspection Service? The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office? And how cool would this be, by the way, to have such cinematic heroes? C’mon, Hollywood: Not everyone has to be a cop.

It’s also one the movies Cagney made during a contract dispute with Warner Bros. Back in 1930, he’d signed a 40-week deal but somehow, after he became a star, the contract kept going into perpetuity—like the reserve clause in Major League Baseball—which meant he was overpaid for a few weeks and underpaid ever after. In the mid-1930s, he split and made two movies for “poverty row” studio Grand National Pictures. This was the first. Neither did well and they helped sink the studio.

It’s also one the movies Cagney made during a contract dispute with Warner Bros. Back in 1930, he’d signed a 40-week deal but somehow, after he became a star, the contract kept going into perpetuity—like the reserve clause in Major League Baseball—which meant he was overpaid for a few weeks and underpaid ever after. In the mid-1930s, he split and made two movies for “poverty row” studio Grand National Pictures. This was the first. Neither did well and they helped sink the studio.

It’s also Cagney’s third and final go-round with Mae Clark. Maybe more notable: no grapefruit in the face (“The Public Enemy”) or dragging her across the floor by her hair (“Lady Killer”). Just a few hat jokes.

It’s just not notable as a movie.

Henry, Henry, Harry or James?

Here’s the plot: After Johnny Cave’s boss, Joel Green (Wallis Clark), is put in the hospital by corrupt ward boss Marty Cavanaugh (Robert Gleckler), Cave becomes the acting head of Weights & Measure. He then shows the ropes to his newest agent, and comic-relief Irishman, Pat Haley (James Burke), by catching chiselers adding weight to chickens and strawberries and the like at a local market. He does the same at a gas station. Then Cavanaugh shows up at Cave’s office and tries to make a deal. He tosses some of Cave’s pennies out the window to make a point, so Cave tosses Cavanaugh’s hat out the window to make the opposite point: Buzz off.

Since this is exactly what Green warned him about—Cavanaugh trying to bribe him—Cave should be on his toes. He isn’t. Without a struggle, he’s kidnapped by two of Cavanaugh’s men who then frame him for drunk driving and reckless endangerment. After that, he should definitely be on his toes, but no: He gets suckered again. In a back stairwell, a former wrestler, Joe Burton (Joe Sawyer), knocks him out and steals evidence against Abel Canning (Henry Kolker), who’s not only the head man but the boss of Cave’s fiancée, Janet (Clark). Luckily, Burton tries to chisel the chiselers—demanding an extra $5k rather than destroying the evidence. In the end, Cave and the cops finally get the goods on Canning and Cavanaugh. As for the mayor who tried to bribe Cave earlier with a sinecure? Who knows? All we know is Cave pushes the cops out of Burton’s room so he can beat up Cavanaugh. The End.

Yeah, kind of a mess. Kind of episodic. But there’s a reason.

The movie is based on three short stories by James Edward Grant that appeared in The Saturday Evening Post in 1933 and ’34. Each story is self-contained. Each has its specific villain.

- “Full Measure” (June ’33) is the Cavanaugh story. He tries to threaten/bribe Cave, then kidnaps and frames him for armed robbery. At the police station, Cavanaugh tries to strongarm Cave again; except Joel Green is there to tape-record the bribe. Cave then shoves the cops out of the holding area to beat up Cavanaugh.

- “Johnny Cave Goes Subtle” (March’34) is the Joe Burton one. Cave is now acting head of the dept. (Green is in the hospital from health reasons), and the villain is a coal magnate named Anson B. Revell, who hires Burton to steal Cave’s evidence. After getting beat up in the stairwell, Cave fingers Burton in the police mugshot book. Cave then frames Burton with counterfeit dough, Burton confesses, Cave confesses the money wasn’t counterfeit, then he beats up Burton in the police holding area.

- In “Larceny on the Right” (Sept. ’34), Cave is now head of the dept. First, the mayor offers him a sinecure, then there’s a shakedown from Commissioner Hanlon, who frames Cave in the media. “Public sentiment is a funny thing,” he says. “The same people writing you fan letters will be the first to cheer when you get the bounce. It won’t be necessary to prove you have been tipping the till. The accusation will be enough.” Distraught, Cave runs into his former boxing opponent, and onetime bootlegger, Pete “One-Round” Reilly, who’s having a bon voyage party before leaving for England. (In the movie, he appears at the 11th hour.) Eventually, all is made right. I forget if Cave beats anybody up in the end.

That’s the source material, and unfortunately the screenwriters just kind of mashed everything together. They made Hanlon a police captain and a good guy. And they turned Janet’s boss, Canning, into the main bad guy. But it doesn’t cohere. It’s too many villains pursuing our hero in similar ways.

None of these stories are online, by the way. I read them in old, bound editions of The Saturday Evening Post at the downtown Seattle library. I was trying to see if the dialogue I liked came from the stories. Here’s an example: When Cave’s boss makes him acting director, he asks him to keep his fists in his pockets. At the gas station, though, the chiseling attendant starts a fight, and Johnny decks him. Then he looks at his fists, forlorn.

Pat: Did you break your hand?

Johnny: Nah. A promise.

My favorite: Johnny shows up late for lunch with Janet. Even as he’s getting chastised, his eyes keep drifting toward the top of her head. Finally he says the following:

My best friend gets hit by a streetcar and winds up in the hospital, civil war in Spain and earthquakes in Japan, and now you wear that hat.

The writer of the short stories, James Edward Grant, is an interesting case. Shortly after these stories were published he moved to Hollywood, where he quickly became one of John Wayne’s favorite screenwriters. (Among other films, he wrote Wayne’s paean to HUAC, “Big Jim McLain.”) But the lines I liked aren’t in his stories. So they came from one of these guys:

- Henry McCarty, 32 credits, mostly silents, with “The Lodge in the Wilderness” (1926) his most famous by IMDb’s algorithms. This is his second-to-last picture, but he lived another 20 years.

- Henry Johnson, 34 credits, with “$10 Raise” (1935), his most famous. This is his third-to-last picture. He also lived another 20 years.

- Harry Ruskin, 64 credits, all talkies, with “The Postman Always Rings Twice” (1946) his most famous. “Great Guy,” which gives him an “Additional Dialogue” credit, is one of his earlier pictures.

If I had to make a guess, I’d go Ruskin, who also wrote a book called “Comedy is a Serious Business.” It’s out of print now.

Lost in transcription

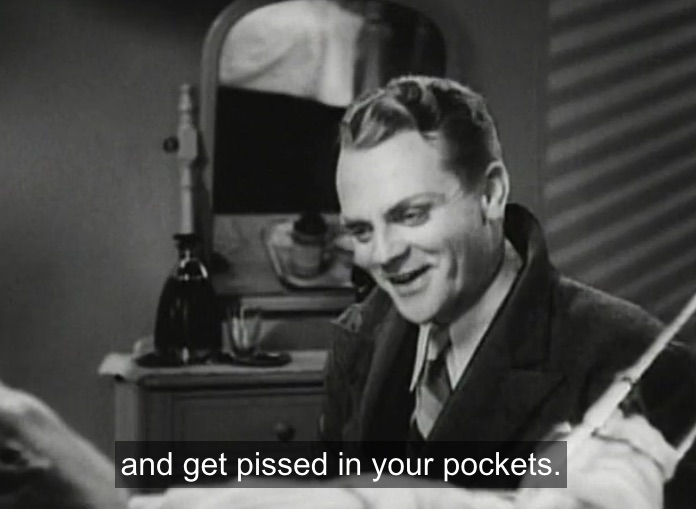

Because of Grand National’s bankruptcy, “Great Guy” entered the public domain decades ago, so a lot of versions are simply copies of copies. The one I saw via Amazon Prime was almost blurry—with the shittiest subtitles I’ve ever seen. Early, Green tells Cave: “Keep your fists in your pockets.” This is how it got transcribed:

And when Pat Haley is chatting up a pretty girl with his usual blarney, “Do you know I’m the first son of the first son of the first son for 600 years straight down to—” Cagney finishes the thought: “Haile Selassie.” It’s a small joke, going for the Emperor of Ethiopia rather than anyone Irish; but in the transcription they shortened Haile Selassie’s name a bit. To this:

Hey.

Cagney still has energy and that great disgusted look he gives crooks. He and Mae Clark still have a spark. But “Great Guy” isn’t notable—despite all the notations I've made above.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)