Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

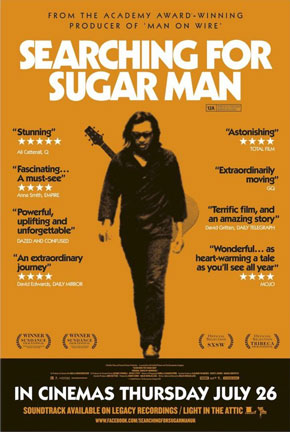

Searching for Sugar Man (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Searching for Sugar Man” is a good documentary about a great story.

In the 1970s in South Africa, so the story goes, there were three albums in every white, liberal (read: anti-Apartheid) home: “Abbey Road” by the Beatles; “Bridge Over Troubled Water” by Simon and Garfunkel; and “Cold Fact” by Rodriguez. Everyone listened to Rodriguez. “He was the soundtrack to our lives,” says record-shop owner Steve Segerman, known to his friends as “Sugarman” after Rodriguez’s signature song. It just took awhile for South Africans to realize that they were the only ones listening. It took them awhile to realize that while everyone knew the Beatles, nobody anywhere knew anything about Rodriguez.

Legends about the man grew. Creation stories were perpetuated. Apparently an American girl with a South African boyfriend brought the first Rodriguez cassette tape into the country in the early 1970s. End times were debated. Apparently in an early 1970s concert he’d poured gasoline on himself and lit himself on fire. No no, he’d greeted the indifference of a tepid crowd by putting a gun to his head and blowing his brains out.

Searching for Rodriguez

Decades later, in 1996, Segerman wrote the CD liner notes to Rodriguez’s second album, 1971’s “Coming from Reality,” and, after owning up to the complete lack of information about the man, asked, “Any musicologist detectives out there?” There was: journalist Craig Bartholomew-Strydom, who had his own list of stories to pursue, the fourth of which was: How Rodriguez died.

This is what he had to go on: a dead record label; a few grainy photos; lyrics. They assumed Rodriguez was American but didn’t know which city. “Inner City Blues” contains the line, “Going down a dusty Georgian side road.” So maybe the South? “Can’t Get Away” referenced being born “in the shadow of the tallest building.” So maybe New York? Bartholomew-Strydom follows the money, like Woodward and Bernstein, but it dead-ends in southern California.

He was about to give up when he honed in on another line from “Inner City Blues”:

Met a girl from Dearborn, early six o'clock this morn

The sad thing isn’t that Bartholomew-Strydom had to look up Dearborn in an atlas when almost any American could have told him it’s in Michigan; the sad thing is that that the documentary has already told us that Rodriguez is in Michigan. Early on, we hear interviews with his Detroit record producers, who lament what happened to him. We talk with people who knew him from the streets of Detroit. They say he was kind of a wandering mystic: a cross between a poet, a shaman and a hobo.

So why does Malik Bendjelloul begin his doc this way? It leaves the audience in the awkward position of waiting for its heroes, Segerman and Bartholomew-Strydom, to come up to speed.

Maybe Bendjelloul begins this way because the lamentations of colleagues reinforce the notion that Rodriguez is dead. Because that’s the big reveal halfway through the doc: He’s not dead. He’s alive. He’s been working construction and renovation in Detroit never knowing he’d become a music legend halfway around the world.

For South Africa, it’s as if Elvis has turned up alive. Most refuse to believe it. Most think it’s a hoax. Because how can Elvis and Jim Morrison and John Lennon still be alive? The world doesn’t work that way. It doesn’t give us that gift.

In subsequent interviews with the documentarian, Rodriguez, born Sixto, reminds me of artistic types I’ve known who have an ethereal matter-of-factness about them. He’s not there but amazingly present. He seems disconnected but connected to something bigger. Asked if he enjoys construction work, he says, “It keeps the blood circulating.” Asked if he knows that in South Africa he’s bigger than Elvis or the Beatles, he replies, “I don’t know how to respond to that.”

The rest of the doc is, in a sense, recognition, at long last recognition, as well as reunion, or, more accurately, union, since he and South Africa have never known each other. In 1998, he travels there with his daughters for a concert. At the airport, limos pull up and the Rodriguezes stand aside for the VIPs before realizing they are the VIPs. They expect small venues and play to rapt, screaming crowds in sold-out arenas. He goes from being a loopy, wandering guy who does construction (in America) to being a music legend (in South Africa). But he stays in America. He keeps working construction. He keeps the blood circulating.

Searching for why

That’s the story, and it’s a great story, a powerful story, a story that couldn’t exist today. South Africa needed to be isolated from the rest of the world, via Apartheid, and the world needed to be not-yet-connected, via the Internet, for the story to work: for a legend to grow in isolation.

But here’s what the doc doesn’t answer:

- What happened to all the money South Africans spent on Rodriguez’s albums? He never saw a cent of it.

- Why did Rodriguez catch on in South Africa? Some of his lyrics are mentioned, particularly “I wonder/How many times you had sex” as an eye-opening notion. Yet South Africa did have the Beatles. They had the Stones. Weren’t their eyes already open?

- Why didn’t Rodriguez catch on in black South Africa? A consequence of Apartheid? A consequence of his music?

- Why did he never catch on in the States?

This last one is the main one for me. The doc, focusing on South Africans, and created by a Swede, isn’t curious enough about the lack of curiosity in America about Rodriguez. I’ve been listening to the soundtrack for a solid month now and love it. It’s kept me going through the ups and downs of the 2012 presidential election. It feels more relevant than most contemporary music.

At times Rodriguez comes off like a soulful Bob Dylan, and, in 1970, that should’ve worked in his favor. That’s what everyone was looking for. John Prine, Steve Forbert, Bruce Springsteen: they were all new Bob Dylans. Rodriguez is so obscure he’s not even mentioned in Loudon Wainwright’s song, “New Bob Dylans.”

OK, let me admit that, yes, there’s no better lyricist than Dylan. He’s at another level, and Rodriguez, while good, is several levels below. But Rodriguez has his moments. The awfulness of war and the thanklessness of medals has been batted about by artists for a century. In Dylan’s “John Brown,” it’s the protagonist’s mother who urges her son off to war to get medals. There, he realizes he’s a puppet in a play and when he returns, injured, he tells her so. This is the last stanza:

When he turned away to go, his mother acting slow,

As she saw that metal brace that helped him stand.

But as they turned to leave, he pulled his mother close,

And he dropped his medals down into her hand.

Rodriguez’s take, from “Cause,” is also about mothers and sons, but feels truer and more poignant:

Oh but they’ll play those token games

On Willie Thompson

And give a medal to replace the son

Of Mrs. Annie Johnson

I keep thinking of these lines, too, from “Crucify Your Mind.” Any artist does. Any person does:

And you claim you got something going

Something you call “unique”

Thirty years later, Rodriguez still sounds vibrant and true. In “Searching for Sugar Man,” the people who knew, his record producers, still rack their brains about why he didn’t catch on. Should have I added more strings here? Less there?

But at one point, someone, I forget who, mentions his name: Rodriguez. They wonder if that’s the issue. They wonder if people dismissed him as Latin music. There’s no way to measure this, of course, or prove such a negative, but that’s my bet. I bet Americans thought that if they listened to someone called “Rodriguez” they would get Jose Feliciano, so they didn’t bother. But halfway around the world, people with less options had more open ears.

Overpaid dues

To me, that’s the great irony of the story of Rodriguez that “Searching for Sugar Man” doesn’t underline enough. A kind of veiled racism doomed Rodriguez in his home country; but talent and circumstances allowed him to prosper in a country that had the one of the most racist governments, and one of the most segregated societies, in the world.

From “Cause”:

Cause they told me everyone’s got to pay their dues

And I explained that I had overpaid them

Indeed. But the ending is happy, for both Rodriguez and South Africa. And for us.

—November 3, 2012

© 2012 Erik Lundegaard