Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

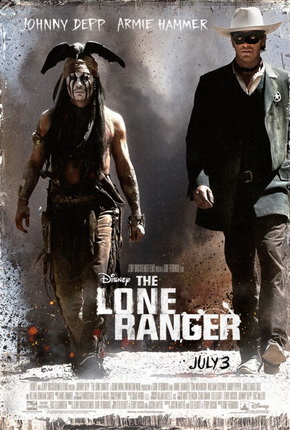

The Lone Ranger (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Come back, Klinton Spilsbury. All is forgiven.

Gore Verbinski’s “The Lone Ranger” isn’t quite as bad as 1981’s “The Legend of the Lone Ranger,” starring Spilsbury—that would take real effort—but the latter had excuses. It was made in an era before over-the-top heroism once again became the default at movies, and the filmmakers didn’t seem to know what to do with their legendary character—a former Texas Ranger who wears a mask and has an Indian companion and shoots guns, pow pow. So they made him a lawyer, not a ranger, who uses silver bullets because he can’t shoot straight. To be honest, he should’ve been called “The Lone Lawyer.” “The Lone Ranger” feels like false advertising.

| Written by | Justin Haythe Ted Elliott Terry Rossio |

| Directed by | Gore Verbinski |

| Starring | Armie Hammer Johnny Depp William Fichtner Helena Bonham Carter |

Now it’s 30 years later, when we like our heroes any way we can get them. Give us our wish-fulfillment fantasy already. Tell us that story again, Daddy.

So what do director Verbinski (“Pirates of the Caribbean”), screenwriters Ted Elliott (“Pirates”), Terry Rossio (“Pirates”) and Justin Haythe (“Revolutionary Road”), give us?

You don’t want to know.

The Tone-Deaf Ranger

The Lone Ranger, John Reid (Armie Hammer, trying), is a lawyer again. He’s a city boy, a tenderfoot, a dude. He grew up in Colby, Texas, but went away to law school, and apparently became a dim bulb and a naïve priss there. Throughout most of the movie, he assumes that right makes might; he assumes that businessmen represent civilization; he assumes—and this in Texas in 1869, mind you—that power comes out of a law book rather than the barrel of a gun.

He’s a fool.

Guns? “I don’t believe in ‘em,” he tells his older brother, Dan (James Badge Dale), a captain of the Texas Rangers. “You know that.”

Everyone prefers Dan. John’s one-time girl, Rebecca (Ruth Wilson), marries Dan and has a kid (Bryant Prince) by him. Even Tonto (Johnny Depp) recognizes Dan as the true warrior. “I would have preferred someone else,” Tonto tells John after he’s stuck with him. “But who am I to question the Great Father?”

In the first act, John Reid allows Butch Cavendish (William Fichter) to go free. Tonto is about to kill Cavendish but John stops him and Cavendish escapes and this sets up everything else. It sets up the ambush at Bryant’s Gap and the massacre of the Texas Rangers. Because John falls off his horse, Dan has to return for him and gets shot as he reaches for him. John, barely alive, then sees Cavendish cutting out his brother’s heart. Literally.

But that should toughen up our hero, right? That should set him right about the ways of the world and put him on the path to revenge.

Nope. John remains a fool until the last 20 minutes of the movie. His head is dragged on the ground, then over horseshit, then Tonto tells him to wear a mask. “Comes a time, Kemosabe,” Tonto says, “when even good men must wear mask.” The mask becomes a running gag. “What’s with the mask?” everyone asks. When he tells Tonto’s fellow Comanches who suggested it, they bust out laughing. Because they know Tonto is screwed up in the head. He’s a fool, too. For most of the movie, our hero is the fool of a fool.

As for why Tonto is a little crazy? Years ago, as a child, he inadvertently caused the death of his people at the hands of two men: Cole (Tom Wilkinson), now a businessman and railroad representative, and Cavendish, his disreputable flunky. He traded them a watch for information, and that led to a massacre.

Both the Lone Ranger and Tonto, in other words, are created out of massacres they inadvertently caused. They are tragic figures yet the movie treats them as comic relief. “The Lone Ranger” is one of the most tone-deaf movies I’ve ever seen.

Everything and the kitchen sink

What’s special about this Lone Ranger? Silver, the spirit horse, recognizes him as a spirit walker, a man who can’t die, but it’s Silver who’s special. He can ride off rooftops and over trains. The Lone Ranger is buried up to his neck by the Comanche, and covered in scorpions, and Silver licks off the scorpions and pulls him out. Silver is the true hero here. The Lone Ranger is part laughing stock, part chosen one. He only survives because he can’t be killed. Nice trick.

Plot? Cole, giving pretty speeches before the populace, wants to unite the nation via railroad, because whoever controls the rail controls the country. For this to happen, though, the rail has to go through Comanche land, so Cavendish’s gang raids settlements dressed as Comanches, which revokes the treaty, which puts their land up for grabs. Dan Reid, a friend of the Comanche, figured this out. That’s why the Bryant Gap ambush. The Comanches themselves are later massacred—ripped to shreds—by an early Gatling gun while the Lone Ranger and Tonto, nearby, are avoiding a runaway train via handcar—that little railroad see-saw thingee most of us first saw in a cartoon. Once again, the tragic is juxtaposed with the comic to perplexing effect.

Meanwhile, Rebecca, who has lost a husband, is attacked by the Cavendish-Comanches and witnesses her black help being murdered. With her son, she’s taken before Butch himself. Eventually she makes it back to Cole, who has always desired her. But this is a dull subplot and Wilson does nothing with the role.

Meanwhile, Barry Pepper plays a George Custer-like cavalryman, who is supposed to come to the rescue but merely contributes to the slaughter of innocents. Then he doubles down on that slaughter so he doesn’t have to face the first fact.

Meanwhile, Helena Bonham Carter plays Red Harrington, a western madam with a fake ivory leg that masks a gun—like an early version of Rose McGowan in “Planet Terror.” She’s the kitchen sink of the movie.

Meanwhile, all of this is being told, believe it or not, by an aged Tonto in San Francisco in 1933. When the movie began, and I first saw these words on the screen, “San Francisco, 1933,” I had a glimmer of hope. “Oh!” I thought. “Good idea. Wonder what the Lone Ranger is doing in the 20th century?” Except we never find out. Instead we visit an amusement park, where a kid, wearing a mask and a cowboy hat, visits a Wild West exhibit. There’s the mighty buffalo, there’s a grizzly bear, and there, according to the plaque, is “THE NOBLE SAVAGE: In his natural habitat.” The kid peers closer and the Indian comes to life. “Kemosabe?” a wizened Tonto asks. Then, with a few interruptions along the way, he tells the kid the story. It’s like “The Princess Bride” but without any of the charm. It’s kind of creepy.

More, it means that no matter what happens in Colby, Texas, in 1869, Tonto winds up as a sideshow exhibit in San Francisco in 1933.

If you’d given me a week, I couldn’t have come up with a sadder end for Tonto than that.

—July 4, 2013

© 2013 Erik Lundegaard