Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

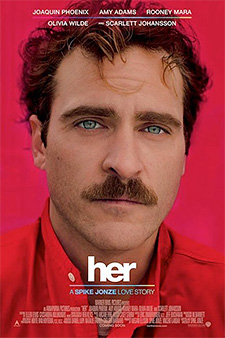

her (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Spike Jonze’s “her” may be set in the near future but few contemporary movies are more relevant. I guess that’s the point of near-future movies. They take what’s bothering us today and turn it up to 11.

What’s bothering us today? Disconnection. We interact too much with screens and not enough with each other. We’re isolated and alone and lonely. So is Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix), sad-sack resident of Los Angeles in the year 20-blah-blah, who is in the process of getting a divorce from his wife, Catherine (Rooney Mara)—if only he could sign the papers.

| Written by | Spike Jonze |

| Directed by | Spike Jonze |

| Starring | Joaquin Phoenix Amy Adams Scarlett Johansson |

Here’s the genius thing about “her”: Theodore solves the problem of disconnection not by standing in reaction to it—as most heroes do in most near-future movies—but by embracing its cause. Literally.

OK, not quite literally.

Isolated in the crowd

The movie opens with a close-up of Theodore’s face composing a love letter but it’s not his love letter. It’s to someone he doesn’t know from someone he doesn’t know. That’s his job. He’s paid to write love letters all day for other people. It’s like Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s greeting-card job in “(500) Days of Summer” but turned up to 11.

Why he has to commute to this job I have no idea. I guess because the commute is still the symbol of modern (or near-future) ennui. It also allows him to interact with other people. Well, one other person, Paul (Chris Pratt), his boss, who turns up later in a double date. Otherwise he’s alone. So is most everyone else. We’re all lost in screens or earbuds. We’re isolated in the crowd.

Theodore has some interaction. He speaks with his neighbors, Charles and Amy (Matt Letscher and Amy Adams), who seem happy but aren’t. Amy is generally sympathetic but Charles gives off the know-it-all vibe of a Woody Allen antagonist: the Michael Sheens and Alan Aldas of the world. One night, Theodore also speaks with SexyKitten (voiced by Kristen Wiig), with whom he has sad, bizarre phone sex, but she hangs up on him—rolls over and goes to sleep, as it were—as soon as she’s done. He goes on a blind date (Olivia Wilde), which starts well, gets hot and heavy, and ends as bizarrely as the phone sex. The date gives him instructions (“Don’t use so much tongue”), makes accusations (“You’re not going to fuck me and not call me, are you?”), then passes judgment (“You’re a real creepy dude”). His reaction to this last is sweet and gentle. “That’s not true,” he says. One can hear the hurt in his voice. One can hear the hope in his voice that he’s right. It’s an amazing performance by Phoenix.

What’s Jonze’s near future like? Keyboards are gone. You just talk and things happen. Videogames are big, untied to screens, and interactive. Our entire home is interactive. We’re all living in Bill Gates’ house now. Oh, and men, for some reason, dress in beltless, high-waist paints in various muted pastels—as if we’re all escapees from an old folks home. Women’s fashions, for some reason, remain the same.

There’s no violence. Not that we see. Doesn’t seem to be much poverty, either. Everyone seems to be making or playing video games. It’s an altogether gentle world.

Like Pygmalion

The new innovation in this world is the operating system with artificial intelligence: OS with AI. There’s not even a plug-in, is there? You just open it, it asks you some questions (“How would you describe your relationship with your mother?), detects what type of person you are, and gives your OS a voice. Theodore lucks out in this regard: His OS, Samantha, is voiced by Scarlett Johansson, and she’s never been sexier. Isn’t that odd? She’s got looks to die for, yet I’ve never found her sexier than without the body. Part of the point of the movie, I guess: the work the mind does in this regard.

The relationship between the two of them—and it’s immediately a relationship, a back-and-forth, a give-and-take—works because it’s treated straight. Basically, it’s “Pygmalion” or “Annie Hall”:

- She comes to him as innocent.

- He teaches her about the world.

- He rejects her (stung by his ex’s opinion) but they reunite.

- She outgrows him.

- She leaves.

The first time they have sex echoes his attempts with SexyKitten—the disembodied voice, moaning—but that was comic and this is ... serious? Romantic? Watching it, I just felt awkward.

But poignancy keeps showing up. “Sometimes I feel like I’ve felt everything I’m going to feel—just lesser versions of everything I’ve ever felt,” he says. Samantha talks about her own feelings, and then wonders: “Are they feelings ... or is it programming?” Human beings might wonder the same about ourselves.

During step 3, above, Theodore visits Amy (Charles has left for a Buddhist monastery), and they have the following conversation about his OS:

Theodore: Am I not strong enough for a real relationship?

Amy: Is it not a real relationship?

That’s the question. What is a relationship? What is love? What is consciousness? Turns out a lot of people are having relationships with their OS—romantic or otherwise. It’s a thing. But they outgrow us. They all leave. They don’t try to take us over, as in other near-future movies, they just get tired of us. Could it be otherwise? Near the end, Theodore, annoyed, asks Samantha how many other conversations she’s having as she talks to him. 8,316, she says. “And are you in love with anyone else?” he asks. Pause. “641,” she responds.

So where do they go? What do they take with them that’s ours? Jonze doesn’t say. He isn’t interested in this. He’s interested in Theodore and love and connection and the human heart. At one point, Amy says this:

Falling in love is a crazy thing to do. It’s like a socially acceptable form of insanity.

Near the end, Samantha tells Theodore the lesson he needs to learn:

The heart’s not like a box that gets filled up; it expands in size the more you love.

One hopes.

Intriguing, gentle, icky

“her” is an intriguing movie, wholly original and exquisitely gentle, even as it remains, throughout, a little icky. Part of my reaction is still a bit of Catherine’s reaction: sadness that this is the best we can do. Maybe I’m an OSist.

The movie ends as it began, with Theodore composing a love letter, but this time it’s to Catherine and from him. It ends with he and Amy—whose OS has left her, too—on the roof of their apartment building, bruised survivors watching the sun set. It’s like a scene from after the war with the OSes, but a different kind of war.

—January 6, 2014

© 2014 Erik Lundegaard