Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

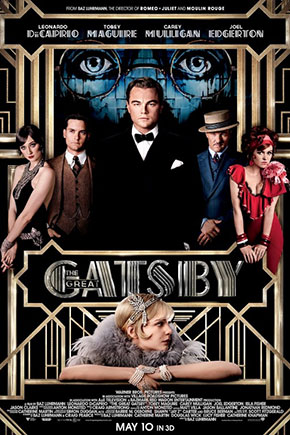

The Great Gatsby (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

In my younger and more vulnerable years, my father, the movie critic for The Minneapolis Star-Tribune, gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. “Whenever you feel like criticising a movie,” he said, “have at.”

That would be a good opening for a scathing review of Baz Luhrmann’s “The Great Gatsby,” but this isn’t a scathing review. I actually liked the movie. For all the complaints I’ve heard about the director’s over-the-top, “Moulin Rouge” style, as well as the anachronism of hip-hop in the 1920s and the absurdity of jazz trumpeters on sweaty New York fire escapes, Luhrmann’s “Gatsby” is about as faithful a literary adaptation as you’re going to get. It brings to life one of the great American novels.

The love light in Leo’s eyes

For one, we get to hear, and sometimes see on the screen, F. Scott’s Fitzgerald’s words. The movie’s conceit is that after all that’s happened Nick Carraway (Tobey Maguire) is in a sanitarium, and he’s telling the doctor his story, and soon the doctor recommends that Nick, a once-budding writer, write it all down, as therapy, which accounts for the literary tone of the subsequent narration. One can’t, after all, describe the valley of ashes, brooded over by the giant eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg, oculist, without sounding written. Let alone “boats against the current.”

Casting helps, too. Neither Alan Ladd (1949) nor Robert Redford (1974) seemed like men who would sacrifice everything for love, but Leonardo DiCaprio has always had the love light in his eyes. He’s Jack Dawson and Romeo, baby. He’s also played charlatan (“Catch Me If You Can”) and obsessed rich man (Howard Hughes, “The Aviator”), and combine them all and you get Jay Gatsby. The one moment he falters is when he turns on Tom Buchanan (Joel Edgerton) with an expression on his face “as if he had killed a man.” We’re supposed to see a hidden Gatsby revealed here. But Leo doesn’t have that in him. There’s anger in his eyes, not murder.

I always imagined Nick Carraway taller than Tobey Maguire but the actor does seem like someone inclined to reserve judgment, a genial type who is the victim of not a few veteran bores. Edgerton is good, too, but… Isn’t his face too working-class for Old Money? He needs to be sleeker. Apparently Ben Affleck and Bradley Cooper were considered for the role. I’d have gone Cooper.

But the casting move that leapt out at me when I first saw the trailer was Carey Mulligan. I always think of Daisy as spoiled and frivolous and kind of awful, yet there’s something inherently sweet about Mulligan. In the film, with her vulnerable eyes, she seems as deeply in love with Gatsby as Gatsby is with her. With this casting move, Luhrmann, the romanticist, turns “Gatsby” into a love story, which it is. But he turns it into a mutual love story, which … Well, we can have our arguments, and it’s been about 10 years since I last read the book cover-to-cover, but “The Great Gatsby” always felt like an unrequited love story to me. It felt like the story of a man who was deeply in love with a woman who was unworthy of that love. (See also: “The Sun Also Rises.”) It felt like the story of a man who takes 99 giant steps toward a woman and the woman who won’t take the one small necessary step toward him.

Gatsby’s great mistake

Or is that step more than small? Luhrmann makes clear that all of Gatsby’s great schemes unravel because, just as his love has demanded much of him, he demands much of his love. He demands from Daisy the absolute: the notion that she never loved Tom. And in that hot New York apartment, where Tom and Gatsby vie for Daisy, and Nick and Jordan Baker (Elizabeth Debicki) are forced to watch, she can’t give him the purity of the absolute. “I did love him once,” she tells Gatsby, in words straight from the novel, “but I loved you, too!”

“You loved me … too?”

DiCaprio gives this a great line-reading. You sense the awfulness of that last word. The deflation in him. The realization of how uncentral he was to her even as she was too central to him. She was the blinking green light at the end of his dock; the woman for whom he created and gave up everything.

That’s Gatsby’s great mistake—the need for the absolute—as it’s the mistake of many young men in love, as it was my mistake when I was young and in love. That love is a greedy kind of love. If Daisy had acquiesced to it here, it would have demanded more of her and eventually consumed them in some other way.

But does a more sympathetic Daisy create a problem with the story? When Nick tells Gatsby, “They’re a rotten crowd. You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together,” and when he tells us in voiceover, “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and creatures and returned to their money…” it feels like he’s talking about a different Daisy than the one we’ve been watching for two hours. It feels like he’s blaming her for the one thing—the hit-and-run, which mostly occurs off-screen—when in the novel he’s blaming her for much more than that.

Tom, of course, is beyond sympathy. He’s the most unsympathetic cuckold in literature. He’s a racist and an adulterer and a meanspirited Old Money bastard fearful of losing his exalted place in the world. He cheats on Daisy with Myrtle Wilson (Isla Fisher), and, in another careless moment, breaks Myrtle’s nose. He doesn’t know or care what other people do, doesn’t know or care what’s going on in the world. When True Love threatens his marriage, he fights back, not because he necessarily loves Daisy, but simply for the fight. To not lose his exalted place in the world. To not lose to New Money.

Why ‘Great’?

I had questions watching the movie that I never had reading the novel. Jordan tells Nick, “He threw all those parties hoping she’d wander in one night.” So why doesn’t she?

Isn’t that odd? That she’d never check out this Gatsby? I mean, is it the West Egg/East Egg thing? Old Money versus New? Robber barons versus bootleggers? Is she waiting for an invitation like Nick receives? Why doesn’t he send her one?

The story is as much about class (both kinds) as it is about love. It’s about the people who have to be careful versus the people who can afford to be careless. Tom carelessly has an affair with Myrtle, and Myrtle carelessly runs out into the middle of the road to flag him down, and Daisy carelessly runs over Myrtle and keeps driving, and all of this carelessness upends Gatsby’s carefully constructed dream. In the end, Gatsby waits for love and gets a bullet in the back. This is Tom’s carefully constructed moment. He implies to Myrtle’s husband, Wilson (Jason Clarke), that the man who ran down Myrtle was the man who had an affair with her, when it was he who had the affair with her and it was Daisy who ran down Myrtle. Gatsby pays for their crimes. He has his own crimes—his work with gangster/bootlegger Meyer Wolfsheim (Amitabh Bachchan), as well as the overwhelming burden of his love—but he pays for theirs.

I don’t buy the sanitarium bit in the movie (Nick seems too level-headed) and I wondered about the lost relationship between Nick and Jordan (although I didn’t miss it), but I liked the ending. Nick finishes his story, this story, and puts it in his briefcase. He looks at the title: GATSBY. Then, in pen, above, he adds a final touch: THE GREAT.

Why ‘Great’? Because Gatsby was worth the whole damn lot of them. Because he thought big, and grandly, about love—a worthy pursuit. The green light blinked on and off but his love was constant.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” is great, Baz Luhrmann’s isn’t, but it’s not bad. It’s not bad at all, old sport.

—May 12, 2013

© 2013 Erik Lundegaard