Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

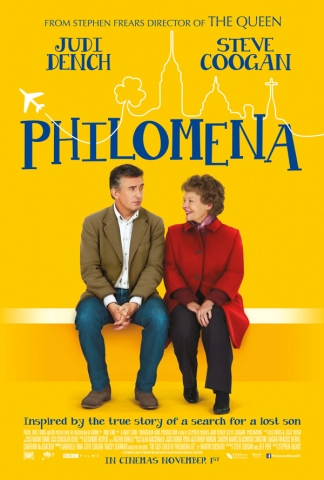

Philomena (2013)

Warning: SPOILERS

The power of Stephen Frear’s “Philomena” lies in the performance and in the message.

A simple woman searches for her long-lost son with the help of an erudite former BBC reporter. Early on, you think the movie is merely an odd-couple road-trip—him, with all his Oxford smarts, learning her simple wisdom—and that’s certainly part of it. You also think the movie is about the journey (them together) more than the destination (what happened to her son), but halfway through we wind up at that destination, and it dead-ends, and we wonder where the story can possibly go. Is there a path? There is. Through there. Then another dead-end and another path. And we keep squeezing through onto these smaller paths, wondering if we’re going to make it out, until suddenly everything opens up into a field, and we stand there for a second, happy, even as we recognize we’ve been there before. It’s Roscrea, the convent in Ireland where we started. At this point the former BBC reporter, Martin Sixsmith (Steve Coogan), recites the following stanza to the woman, Philomena Lee (Judi Dench):

| Written by | Steve Coogan Jeff Pope (based on the book by Martin Sixsmith) |

| Directed by | Stephen Frears |

| Starring | Judi Dench Steve Coogan Sophie Kennedy Clark Mare Winningham |

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

She’s effusive, and asks if he came up with it just then.

Martin (slightly embarrassed): It’s T.S. Eliot.

Philomena (unembarrassed): Oh. Well, it’s still very nice.

It’s the “still” that gets me. It’s the way Dench says it. It’s the way Dench says everything. She reminds me of my mother and Sixsmith reminds me of me. I don’t see me in many movies, and I see my mother less often, so it’s nice to see us up there for a change.

The greater sin

In 1951 Philomena Lee (Sophie Kennedy Clark) met a young boy at a carnival, and after a candied apple knew sin. Her family, ashamed of the out-of-wedlock pregnancy, sends her to Roscrea, where the nuns grill her. “Did you take your knickers down?” they ask. “Did you enjoy your sin?” She signs a document giving the convent the right to put her child up for adoption; then she and other unwed mothers work off what they owe in the laundry room. They’re allowed an hour a day with their child. Philomena’s is named Anthony. At age 3 he’s taken away. She hasn’t seen him since.

Why does Philomena tell her daughter, Jane (Anna Maxwell Martin), about the half-brother she never knew on the 50th anniversary of his birth? She still considers herself a good Catholic and for years thought that what she’d done was a sin, a great sin, so she’d kept it hidden. But wasn’t keeping it hidden a sin as well? Which was the greater sin? She didn’t know. So her gut decided.

Later, Jane is serving wine at a party when she overhears Sixsmith talking to friends, rather uncomfortably, about his plans for the future. He’d worked for the Blair government but left under a cloud. The cloud actually surrounded the Blair administration but most people just remember the cloud. Sixsmith is thinking about writing a book on Russian history—everyone’s lack of interest is a running gag in the film—so Jane tells him about her mother. He’s dismissive at first. Human interest stories, he says, are for “weak-minded, vulnerable and ignorant people.” Then he realizes the insult.

There’s a lot of this: Sixsmith acting slightly rude and/or academic in that Steve Coogan manner, then slightly abashed in that Steve Coogan manner. Philomena is his opposite. She’s sweet but slightly daft. Mostly it works. As here:

Jane [to her mother]: What they did to you was evil.

Philomena: No no no. I don’t like that word.

Martin [taking notes]: No, it’s good: Evil. [Looks up.] Storywise.

Or here:

Philomena: Do you believe in God, Martin?

Martin: [Exhales] Where do you start? I always thought that was a very difficult question to give a simple answer to. ... Do you?

Philomena: Yes.

Or the scene on the back of the airport cart when she goes on and on about the trashy book she’s just finished despite his complete lack of interest. But he’s polite. He says it sounds interesting and she pushes the book on him. He scans the back cover. “I feel like I’ve already read it,” he says dryly. Beat. “Oh, there’s a series.”

The even greater sin

In scenes reminiscent of Coogan’s mockumentary, “The Trip,” Sixsmith and Philomena drive to Roscrea to find of what they can. The nuns there are distant and unhelpful. The records of what happened to Anthony are gone, too, destroyed in the fire in the 1970s. He later learns the fire wasn’t a fire-fire but a burning of records.

Back in the 1950s, most Irish children were adopted by wealthy Americans, some of the few people in the postwar world who could afford the £100 pricetag; and while the British government isn’t helpful with its records, Sixsmith, who once reported from Washington, D.C., thinks they’ll have better luck with the Yanks. That’s the rationale for flying to the states. It feels unnecessary, but it furthers the road trip and the comedy of manners. In a D.C. hotel buffet, for example, Philomena is overfriendly with the Mexican staff (“I’ve never been to Mexico but I hear it’s lovely.” Beat. “Apart from the kidnappings.”), while Sixsmith isn’t friendly enough. But it’s there he finds the answer to her question. A friend emails an old newspaper photo from 1955 showing a Dr. and Mrs. Hess returning from Ireland with two adopted children, Michael and Mary. A quick internet search turns up Michael Hess, senior counsel in the Reagan and Bush Sr. administrations, who died of AIDS in 1995. Philomena has found her son only to lose him again.

That’s the dead-end. So where do you go?

To these questions: Did he miss me? Did he think about me? Did he try to find me as I tried to find him? That’s when the trip to the U.S. makes sense. They meet the sister, Mary (Mare Winningham, in a great, thankless performance), who seems to know little about the inner life of her brother, along with a few of Michael’s friends; but in Michael’s lover, Pete Olsson (Peter Hermann), they run into another dead-end. He refuses to talk to them, even after Sixsmith “doorsteps” him. It’s Philomena and her moral authority that wins the day.

She learns that not only did Michael try to find her, he visited Ireland and the convent. He met with the nuns, including Sister Hildegarde (Kate Fleetwood/Barbara Jefford), severe in manner and cat’s-eye glasses. He’s buried there. But they told her they didn’t know where he was, just as they’d told him they didn’t know where she was. They kept mother and child apart. Most movies are about absolutes, good guys and bad guys, so I took all of this with a grain of salt. “I’m sure it’s exaggerated for the movie,” I thought.

Nope. From Sixsmith’s 2009 Guardian article:

Separated by fate, mother and child spent decades looking for each other, repeatedly thwarted by the refusal of the nuns to reveal information, each of them unaware that the other was also yearning and searching.

On the return to Roscrea, Sixsmith is full of righteous anger and condemnation. That’s what the movies are often about, too: revenge. Philomena takes another path, and it’s her path that gives the entire movie meaning.

Notre Dame

“Philomena” isn’t perfect. Coogan, who wrote the screenplay with Jeff Pope, pushes the differences between the two characters to an unnecessary comic degree. He turns Sixsmith into too much of a Steve Coogan character and makes Philomena more daft than she probably is.

But Dench is perfect. We get several scenes from the 1950s to demonstrate what Philomena lost, but these, to me, are almost unnecessary. We know what Philomena lost. You just need to watch Judi Dench act.

—December 2, 2013

© 2013 Erik Lundegaard