Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

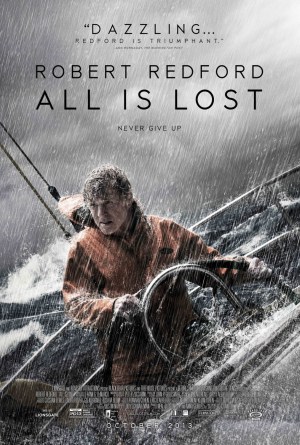

All is Lost (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Do all stories about old men and the sea immediately lend themselves to metaphor? It did with Ernest Hemingway and it does with J.C. Chandor (“Margin Call”) in his new movie, “All is Lost,” starring Robert Redford.

Starring Robert Redford, I should add, and nobody else. You don’t see one other person in the movie. It’s just him and the boat and the sea. There’s hardly any dialogue, or, I suppose, monologue. We get a bit, at the beginning, of the old man reciting lines from a diary. “Thirteenth of July, 4:15 PM,” he says, and then, “I’m sorry.” He says, “I tried.” He gives the movie its title: “All is lost here—except soul and body, or what’s left of them, and a half-day’s rations.” Then he ends as he began:

| Written by | J.C. Chandor |

| Directed by | J.C. Chandor |

| Starring | Robert Redford |

“I’m sorry.”

To whom is he sorry and for what? Exactly what did he try? We don’t find out. We never even find out his name. He thinks, and reacts, and does, but he doesn’t talk much, not even to himself. The lack of words adds to the tension in the movie. It adds to the sense that we’re suffocating, drowning.

That we’re dying.

Storm damage

Eight days earlier, the old man, whom I’ll call Redford, wakes on his 39-foot yacht, the Virginia Jean, to water pouring into the cabin. In the middle of the Indian Ocean, his boat has struck the side of one of those giant metal containers, apparently filled with shoes, that apparently slid off a ship. He extricates himself ingeniously, using an anchor weight on the other side of the ship container, then patches the hole using homemade glue and something resembling gauze. He tests it. It holds. He pumps out the water. He tires, he eats, he sleeps. He watches the sun set and smiles.

But he’s in trouble. The water ruined his electronic equipment so he has no way to navigate, no way to send an S.O.S. And storms are approaching.

I’m a landlubber who isn’t good with his hands, so I’ll leave it to others to say whether Redford makes all the right moves. He seems to. He seems to make smart moves—using everything he has, everything around him—and it doesn’t matter. Storms are coming and he has a hole in the side of his ship.

It was about this point in the movie that I wrote in my notes, “Metaphor for age?” That’s how “All Is Lost” feels. It’s an Ivan Ilyich movie. The world closes in. Options disappear. No matter how smart you are. No matter what you can do with your hands.

The storm comes, the boat overturns, the mast breaks. Worse, the hole in the side is leaking again. Then the boat pitches forward and he’s knocked out. He wakes to water lapping up to the bed in the cabin. It’s waist high and getting higher. The ship groans under the weight. Once again he looks around. Once again he considers his options. They’ve disappeared. They’ve reduced themselves to one: LIFERAFT. Redford gathers what he can before the Virginia Jean sinks into the ocean.

The Lady or the Tiger?

We watch movies rooting for the protagonist—to live, survive, thrive—but some part of me, the critic part of me, remained aware that for this movie to have any meaning Redford has to die.

Even so, it’s tough to hold onto the thought. He reads an old book, “Celestial Navigation for Yachtsmen,” and calculates he’s entering a shipping lane. He encounters two big ships, and tries to signal them with flares, but they keep going. We don’t see anyone on them, they don’t see him. Sharks begin to gather. He’s slowly dying—of thirst, hunger, exposure. His hands aren’t working. He can do less and less. It’s impressive that Chandor and Redford make this interesting throughout. We keep caring. We keep wondering what he’ll do next. We want him to be rescued even though we know he should die.

Amazingly, Chandor satisfies both of these desires.

Redford’s passed the shipping lane, and hope is gone, along with food and water. Then he sees a .. what is it? A small boat on the horizon? Lit up? He wants to signal it but he’s used up all his flares on the bigger ships. So he creates a fire in an old, cut-out plastic container, and feeds the pages of his book into it. He stands and waves. Will the fire get out of control? Of course it will. Will he go into the water? Of course he will. He tries to stay afloat but he’s too tired, too weak, too old, and he sinks. He’s dying just as—no! The other boat, comes over to his raft, attracted by the flames. It flashes its light, searching the dark waters. And something in him, that drive in him, stirs, and he fights and swims up toward that other boat, and we see a hand reach down to grasp his, and we’re reminded—or at least I was reminded—of Michelangelo’s painting of God and Adam on the roof of the Sistine Chapel. And in that moment he’s pulled into the light. The End.

And a second later, the light goes on for us.

We can argue all we want about this ending—is this rescue or death?—but I tend to go with the interpretation that gives a deeper meaning. And the latter interpretation, death, actually encompasses both of our desires. We know the old man should die, and he does; but we want him to be rescued, and he is.

This hasn’t been a very good year for movies, and “All Is Lost” isn’t exactly a fun movie to watch. It doesn’t press our pleasure points throughout the way that most movies do. But then most movies leave us feeling tawdry and unsatisfied afterwards. “All Is Lost” left me feeling still, yet exhilarated. It left me feeling this much more aware of the inevitability of diminishing options.

—October 27, 2013

© 2013 Erik Lundegaard