Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

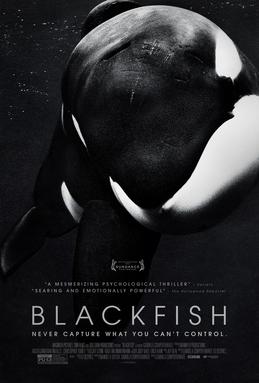

Blackfish (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The best scene in the best movie of 2012 was the moment in “Rust and Bone” when Stéphanie (Marion Cotillard), a former trainer at Marineland who has lost her legs to an orca, returns to her former workplace and stands in silence before a large glass tank. This is what I wrote a year ago:

She pats the glass once, twice. After a moment, a monster looms into view. An orca. The orca? The one who took her legs? One assumes not. One assumes that one has been killed but you never know and [director Jacques] Audiard never says.

I was so naïve. I thought putting down an orca was like putting down a dog, but other factors come into play. Like money.

Actually, there are no other factors. It’s just the money.

Not whales, not killers

Here are some of the things you learn watching Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s documentary, “Blackfish”:

- Orcas are highly social mammals and travel in packs.

- When baby orcas are separated from the pack by hunting vessels, the rest of the orcas stay close and attempt to communicate. They don’t flee. They don’t abandon the child.

- “Killer whale” is a misnomer. Orcas are not whales and they don’t kill people. At the least, there’s no record of them killing any human in the wild.

- Native Americans call them “blackfish.”

- Orcas can live as long as we can.

But the doc is mostly about one orca: Tilikum.

In 1983, off the coast of Iceland, a male baby orca, two years old and 4,000 pounds, was separated from its mother and taken to SeaLand in Victoria, B.C. It was named Tilikum. He performed there for years. The trainers liked him. But in February 1990, a marine biologist and competitive swimmer named Keltie Byrne, 20, slipped into the pool with Tilikum and two females and the whales, mostly Tilikum, held her underwater. She tried to surface and call for help, but she was held under again. She drowned. That was the first.

Apparently SeaLand was a sad little place, poorly run, and when it went under Tilikum was sold to SeaWorld Orlando. He performed there daily. Then in 1999, a 27-year-old man snuck into SeaWorld one night and jumped or slipped into the orca tank. He was found naked and dead atop Tilikum the next morning. Then in February 2010, Dawn Brancheau, a 40-year-old trainer, was pulled into the water by Tilikum. The other trainers eventually distracted Tilikum and he let her go, but by then she was already dead: beaten, drowned, scalped.

That’s when Tilikum was finally put down.

Kidding. He returned to performing shows at SeaWorld Orlando in 2011. Maybe you’ve seen him there. Maybe you paid money to see him. Why not? It’s a free country.

It’s not just Tilikum

The big question in “Blackfish,” unanswered and unanswerable, is this: Why did Tilikum kill Dawn Brancheau?

The corporate line, the SeaWorld line, is that it was a mistake. Dawn was wearing her hair in a ponytail, and Tilikum caught her ponytail, and yadda yadda. It wasn’t malicious; it was user error. Many of the talking heads in the film, former trainers themselves, dispute this. They say Dawn was their best. If it happened to her, they say, it could happen to anyone.

The doc’s line is this: Tilikum, over his lifetime, has been severely traumatized. He was separated from his family at a young age. He was bullied and scarred in captivity, and often kept in tiny 20x30 holding pens. He’s a mammal that was born to swim the ocean and instead swims in a tiny prison of water. He performs tricks to be fed.

We have our doubts about SeaWorld but we’ll never really know the answer.

But there’s a bigger question, unraised, in “Blackfish”: Why do we go to places like SeaLand and SeaWorld to see creatures like Tilikum performing tricks in such unnatural settings in the first place? Why does this appeal to us? So we can see these beautiful creatures close up? In safe settings? Without effort? Even though we know—all of us know, deep down—that this is not the place for them?

“All whales in captivity are all psychologically traumatized,” says one of the talking heads in the doc. “It’s not just Tilikum.”

“When you look into their eyes,” another says about orcas, “you know someone’s home.”

“In 50 years,” a third says, “we’ll be looking back and saying, ‘My god, what a barbaric time.’”

Patricia agrees. We watched the doc together. She only lasted 10 minutes into “The Cove,” the 2009 Academy-Award-winning documentary about the mass killing of dolphins in Japan, because she can’t stand seeing animals suffer; but she made it through “Blackfish.” Even so, she wore a look of horror during its 88-minute runtime. Afterwards, I asked what bothered her: Was it the whales in captivity or the killing of humans?

“Oh, the whales in captivity,” she said. “I could give a shit about the people.”

“Blackfish” is a good starter to a conversation we should’ve had decades ago. Will this conversation go anywhere now that “Blackfish” has been released? Well, you know us.

—December 30, 2013

© 2014 Erik Lundegaard