Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

The Last Sentence (2012)

WARNING: SPÖILERS

In 1996, Swedish director Jan Troell (“The Emigrants”; “Everlasting Moments”) made “Hamsun,” a biopic of the latter years of famed Norwegian novelist Knut Hamsun (Max von Sydow), who infamously sided with Nazi Germany during World War II. It’s a tragedy.

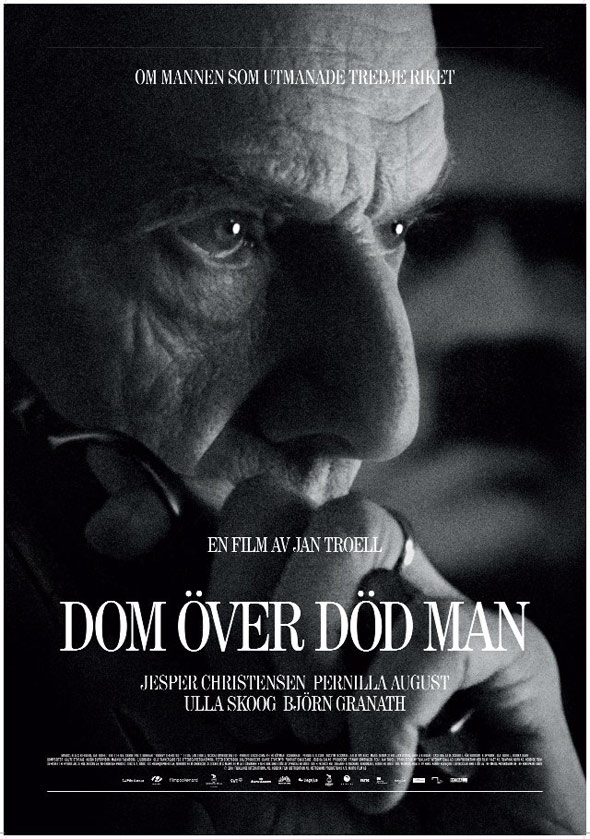

Last year, Troell made “The Last Sentence” (“Dom over dod man”), a biopic of the latter years of famed Swedish journalist Torgny Segerstedt (Jesper Christensen), the editor-in-chief of Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfartstidning (GHT), who was one of the strongest, most strident, and earliest voices against Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany. It, too, is a tragedy.

The lesson? Apparently it’s tough to have a happy ending in Nazi-occupied Europe. Also being on the right side of history doesn’t mean you’re not an asshole.

Two opposing ideas

When I first saw Segerstedt watching newsreel footage of Hitler, I thought, “That’s our hero?” He has a shock of white hair, prominent cheekbones, and something severe and uncompromising in his face. He looks like a drag. He is. Shortly afterwards, we see him at a dinner party giving an overlong toast about “the truth.” He does this while also conducting a public affair with the publisher of GHT, Maja Forssman (Pernilla August, Anakin Skywalker’s mom, y’all). “The sleeper does not sin,” he tells his wife, Puste (Ulla Skoog, in a great performance), before the party. “As you should know,” she replies. “You hardly sleep.”

For the first third of the film, in fact, Troell mostly ignores Hitler and history and focuses on Segerstedt’s infidelity. The cuckold, Segerstedt’s friend Axel Forssman (Björn Granath), handles it all with equanimity and a kind of sad Swedish acceptance, but Puste is less forgiving. She’s full of self-pity but receives little from others:

Puste: What does she have that I don’t?

Ingrid Segerstedt: A newspaper, mother.

And from us? We certainly feel sorry for her. How awful to take a back seat in your husband’s affairs—to not even be able to sit next to him at parties—to be usurped and forgotten in this manner. But any pity we have for her is laced with something else. There’s a quiet moment when Puste sits at Segerstedt’s desk. It’s her way of getting close to him. She doesn’t have him but she has his things. It’s a bit creepy but mostly sad. Then it just becomes creepy. She opens the desk drawer and finds a picture of a girl—“Maja, age 16,” it says on the back—and her face hardens and she tears it up. When she next visits Segerdtedt in his den, stepping over his dogs to bring him tea, and he’s brusque and distracted, she pours scalding water on the dogs.

“The test of a first-rate intelligence,” F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote, “is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still be able to function.” Troell manages this with his characters. Our thoughts, our feelings, are forever conflicted about them. Sure, Torgny should pay more attention to his wife … but she’s such a pain. Yes, he ignores her … but wouldn’t you?

Writing in sand

What’s amazing abut Segerstedt, why a biopic was made in the first place, is not just that he saw the dangers of Nazi Germany; it’s how early.

After the opening newsreel, he writes a screed-like editorial that ends with the line, “Herr Hitler is an insult.” Shortly thereafter, GHT receives an admonishing telegram from Hermann Göring himself, which they celebrate receiving, and which leads to another editorial. About 10 minutes of screentime later, we get news of a fire at the Reichstag building.

Me in the audience: Wait, Segerstedt wrote editorials against Hitler before Reichstag? Wow.

The second half of the movie, after Puste’s death, is more historically relevant but less emotionally resonant. The world closes in: Anschluss, annexation, appeasement, invasion of Poland, yadda yadda. At one point Segerstedt receives a phone call from a Swedish fascist who threatens his life. Segerstedt invites him over for tea. “After that, you can kill me,” he says. His maid, Pirjo (Maria Heiskanen), worries he’s being too flippant but he dismisses the threat. He feels anyone who threatens a man over the phone is a coward and won’t show his face. He’s right. But then one of his dogs is found dead on the grounds from strychine poisoning.

As both Denmark and Norway are invaded, Segerstedt’s voice against Hitler remains strident, and he’s cautioned by the authorities—including, eventually, the King—to tone it down. “You do danger to Sweden,” he’s told. “You are blinded by your hatred of the Germans.” “I don’t hate the Germans,” he responds calmly. “I hate the Nazis.” In a less calm moment, he slaps the face of the foreign minister.

There’s a kind of bitter joke here. Segerstedt warns early and often about Hitler but Sweden is one of the few countries that’s never engaged in World War II. It’s never invaded; it remains neutral. Instead, or maybe as a result, Segerstedt’s battles become internecine. The Swedish police raid the GHT offices and Segerstedt’s voice is muted. An odd banquet is held for him by leftists, in which he’s hailed as a truth-telling knight, and made to ride a horse and carry a lance, but he comes off more buffoon than hero. Finally, his battles become internal. Puste dies, but he hangs on. Maja dies, but he hangs on. He’s haunted by the women in his life: we see them black-veiled and vaguely amused, like Jessica Lange in “All That Jazz.” Then he’s haunted by the purposelessness of his life. He wrote thousands of articles—to what end? “How quickly it passed,” he says. “I have written in sand,” he says.

Outliving Hitler

In the end, he simply wants to outlive Hitler but doesn’t get to do this, either. Sick, bedridden, stubbornly hanging on, the great truth teller is lied to. “Hitler? Is he dead?” he asks. “Yes, he is gone,” he’s told. But it’s March 1945. Hitler has another month to go. Segerstedt does not.

The test of a first-rate movie is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still function. “The Last Sentence” does the former but it doesn’t quite function. Moments resonate (“I have written in sand”) but the whole just sits there. In the end, it’s a movie better in the reviewing than the viewing.

—May 30, 2013

© 2013 Erik Lundegaard