Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

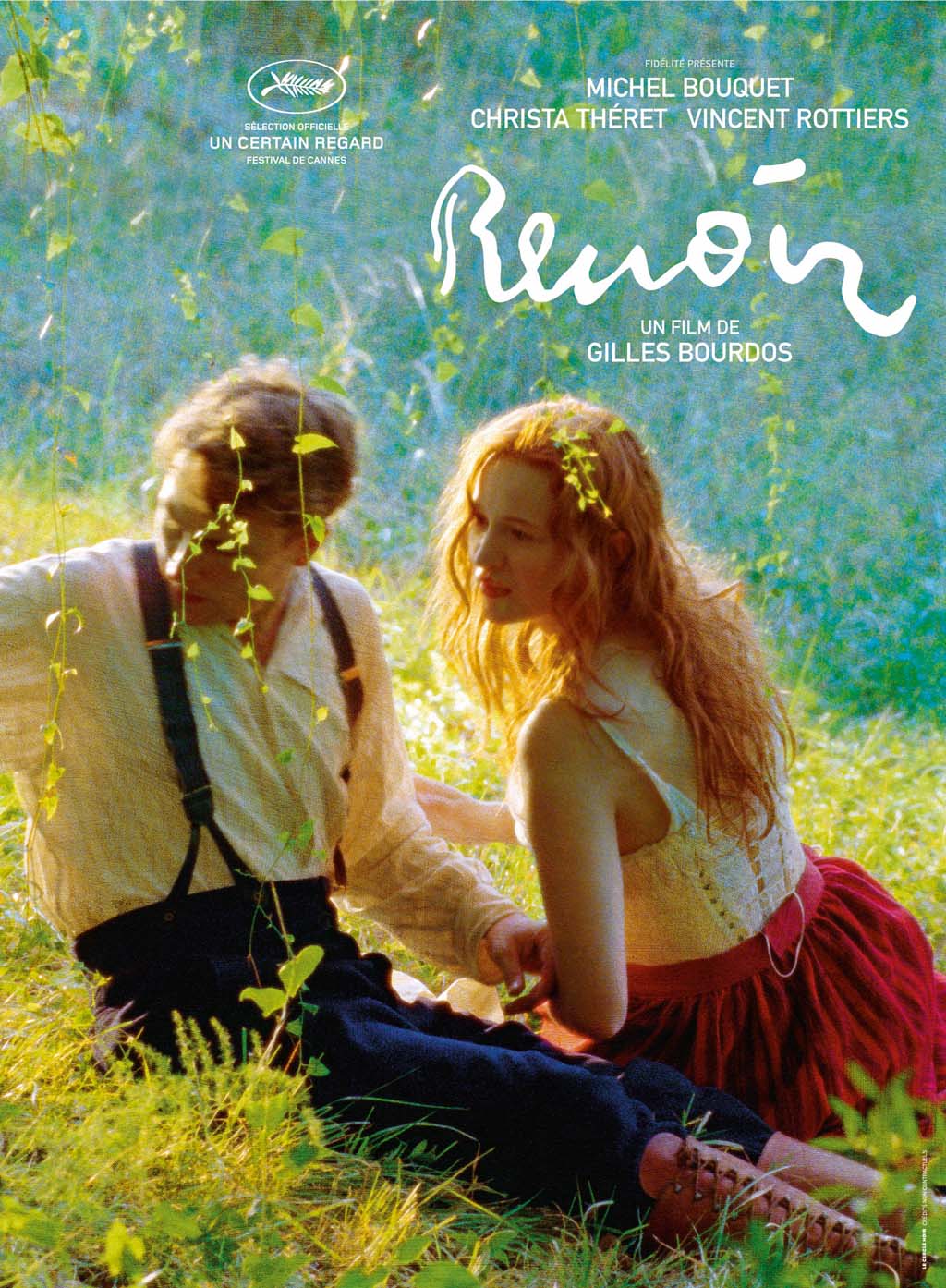

Renoir (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Leave it to a great painter like Pierre-Auguste Renoir to make my father look good. Whatever ways my father embarrassed me when I was growing up, he never described my girlfriend’s tits in exquisite, loving detail the way that Pierre-Auguste (Michel Bouquet) does to his son, Jean (Vincent Rottiers), two-thirds of the way into Gilles Bourdos’ slow, painterly film, “Renoir.”

“Titian would have worshipped her,” Pierre-Auguste says. “Flesh! That’s all that matters! In art and in life!” And, weary in his old age, and suffering from decades of rheumatoid arthritis: “I’d give my right arm for her tits.”

The tits in question belong to Andrée Heuschling (Christa Theret), model and muse to Auguste in art, and instigator and muse to Jean in his film career. Muse and instigator for writer-director Bourdos as well.

“I made the film for Andree Heuschling,” Bourdos told The Los Angeles Times earlier this year. “She is someone who was the link—the junction between the world of painting and the world of cinema, and between the world of Renoir the father and Renoir the son. I think by using her as a focal point, it enabled me to enter the world of these men.”

That’s a great idea, and the movie is beautiful to look at, and there are moments that resonate. But the movie itself doesn’t resonate.

Renoir’s wife

It opens in 1915 along the Cote d’Azur. It’s peaceful but, as Andrée bikes along a country road, there are signs of less-peaceful events taking place elsewhere. Up in the trees Andrée spots a Hun hung in effigy. As the movie progresses the war gets closer. We see injured soldiers by the side of the road. The Renoir estate will be turned into a boarding house for officers. And one soldier will return home.

Andrée, on this day, is simply biking to the Renoir estate to ask after a job as model to the famous painter. She claims Renoir’s wife sent her but a disgruntled angry boy, in a sleeveless shirt and carrying a stick as a weapon, informs her Renoir’s wife is dead. He calls her a liar and runs away. This is Coco (Thomas Doret, “The Kid with a Bike”), Renoir’s third and last son, who will remain angry and disgruntled throughout the movie; but the source of his anger is never fully explained, nor, for that matter, much noticed by others. Is it too much, being the son of Renoir? (At one points, he tosses dark blue pigment over André’s naked body while she dozes on a chaise lounge.) Is it too much, as an adolescent boy, hanging around all of these beautiful naked women? (“Show me your tits,” he says, at another point, to Andrée. Is he still angry over the death of his mother, or the dismissal of his father’s previous muse/model, Gabrielle (Romane Bohringer)? Coco is intriguing but a secondary character.

Despite the lies about Renoir’s wife, if they are lies, Andrée gets the job but seems remarkably unimpressed by her surroundings. She’s upset Renoir is painting apples rather than her. She wants more money. Renoir is amused, enchanted. That night, sleeping, dreaming, he thanks his dead wife for sending him Andrée. “Her skin drinks in the light,” he says.

Andrée first approached the Renoir estate filmed from behind, as does Jean, on crutches, returning from the war. His return is cause for celebration, for both father and help, and for us, too, to further along the story, but the story doesn’t get much further. Renoir continues to paint, his son continues to help, Jean and Andrée eventually fall in love, or into mutually convenient lust, during which Andrée pushes the young man, who had considered a career painting ceramics, toward film, the medium with which he will become an artist himself (“La grand illusion,” “La règle du jeu,” “La bete humaine”).

But we only get suggestions of this later life. Here? Jean heals, and, against the wishes of both his father and Andrée, returns to war, this time in the Air Force. His father, wheelchair bound, stands to hug him goodbye. The movie, like Pierre-Auguste, doesn’t make it into the 1920s. The rest is afterword.

The complications

Moments stand out.

There’s a great shot of the artist dipping his brush in water while the paint swirls slowly down in an orange cloud. I also liked a picnic along the river, during which we see what Renoir is painting, in close-up, and then the camera pans left to what he is painting. It’s all blurry and shadows. The portrait of the artist as an old man with feeble eyesight. “All my life,” he tells Jean, “I got caught up in the complications. Today, I simplify matters.” When Jean suggests rest rather than more painting, his father objects. “I have progress to make!” When his doctor asks what he’ll do when he can no longer hold the paintbrush he responds, “I’ll paint with my dick.”

The old man is driven, as is the young woman, who talks of seizing every chance life offers. But is she too modern? Her body type is right for the period, and for Renoir (veering, as much as modern movies allow, toward the zaftig), but her sauciness, and her look, feel closer to this era. Bourdos may have made the movie for her but he also made her a pain. When Jean, in the beginning of their relationship, finds her flirting with another soldier, he sends her to the kitchen to remind her of her status, and there she struggles uselessly. She demands food, berates the staff, throws Renoir-etched dishes on the floor. When in the middle of their relationship, Jean informs her he’s re-enlisted, she abandons the estate and returns to prostitution. It’s up to Jean to retrieve her.

Would we have been better served seeing how the young Renoir entered the film industry with Andrée, his actress-wife, whom he wanted to make a star and didn’t? Why did he only become a true artist after his separation from her in 1931? Maybe she was his last connection to his father, and he needed to kill his father completely before becoming truly, artistically, himself?

Is that Andrée’s tragedy: serving only as muse to great men? Or is that enough? Most of us have done much, much less.

There’s a great story in here somewhere but it’s not here.

—May 11, 2013

© 2013 Erik Lundegaard