Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

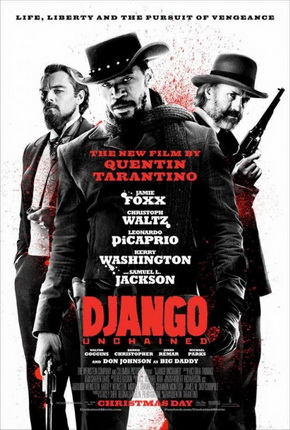

Django Unchained (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The slaughter of Native Americans? The rape of Nanjing? The near-genocides of Josef Stalin or Pol Pot? What is the next historic horror Quentin Tarantino will turn into a spaghetti-western-style revenge fantasy? In the 1990s, QT gave us three complex, pulpy crime stories (“Reservoir Dogs,” “Pulp Fiction,” “Jackie Brown”), and in the aughts three female revenge fantasies (“Kill Bill” I and II and “Death Proof”), and now he’s given us two revenge fantasies of an historical nature: the rising up of the historically downtrodden. “Inglorious Basterds” showed us Jews killing Nazis, including Uncle Adolf, once upon a time in Nazi-occupied France. Now, in “Django Unchained,” a freed slave, Django (Jamie Foxx), kills slavemasters in the deep South—or more specifically, as it’s scrolled across the screen in big 1950s type, M-I-S-S-I-S-S-I-P-P-I—in 1858. “Two years before the Civil War,” QT adds helpfully.

It’s a great idea. History is nothing but groups of people being fucked over, while the movies are all about wish-fulfillment fantasy. So why not meld the two? The Bible is full of revenge fantasies as well. Maybe that’s the next direction? “Quentin Tarantino’s The Bible.” That’s a title he’d dig. He’d dig it the most, baby.

| Written by | Quentin Tarantino |

| Directed by | Quentin Tarantino |

| Starring | Jamie Foxx Christoph Waltz Leonardo DiCaprio Kerry Washington Samuel L. Jackson |

The more-or-less true story of the bounty hunter

Question: Who holds the power in a Quentin Tarantino story? More than the one with the weapon, it’s the one with the story. His movies are conversations punctuated by violence, and the one who holds the floor holds the power.

This is apparent more than halfway through “Django Unchained” when Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) momentarily loses the conversational thread to Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio). Schultz actually looks confused at the dinner table. Someone is telling a story and it’s not him. He should know that when the talking is done a gun will be pointed at his head, since that’s how he usually ends his stories. It’s really this, getting one-upped in storytelling, more than the dogs tearing apart the runaway slave d’Artagnan (Ato Essandoh), that later bothers Schultz. That’s why he: a) insults Candie, and, b) shoots and kills him. He must know he’ll die as a result. But he has to do it. The man can’t abide getting one-upped in storytelling. I’m sure Tarantino, an inveterate storyteller, feels the same way.

The storytelling is what’s right with “Django.” It also indicates where Schultz, or QT, goes wrong.

The power of Schultz’s stories is that they’re more-or-less true. In the beginning, he really is interested in buying the slave, Django, from the slave traders who are moving Django and four others across Texas in 1858. He comes upon them in the middle of the night, driving his absurd little stagecoach with the large plaster tooth bobbing comically on top. The tooth is subterfuge, since he hasn’t worked dentistry in five years. But he is interested in buying Django for a fair price. He’s a bounty hunter, tracking the three Brittle brothers (great name), but he’s never seen them. Django has. That’s why he wants him. But the two white men, the slave traders, aren’t interested in his long-winded story, nor his fancy-pants European vocabulary, and they try to cut his story short, not to mention his bargaining, at the point of a gun. That’s our first shootout. Schultz kills one, leaves the other beneath his own horse, but still pays for Django. Because his story is true.

His next story is even better because every element of it, in the telling, seems crazy, but in the end it all pulls together.

Schultz rides into Daugherty, Texas, accompanied by, as everyone says, “a nigger on a horse.” That freaks them out right away. Then he actually brings Django into a saloon, which is closed for another hour. When the saloonkeeper flees, he pours himself and Django beers and tells him of his plans. He says he’s against slavery, but, for the moment, somewhat guiltily, he’ll use it, and Django, to get the Brittle brothers and the bounty on their heads. After that, he’ll set Django free. Deal? By this time the sheriff, Bill Sharp (Don Stroud), shows up, and Schultz, while explaining matters, shoots and kills him in the muddy Texas street. Now everyone’s freaking. But rather than attempt to escape, Schultz nonchalantly returns to the saloon, keeps telling his story to Django, and let’s opposition forces, led by the local Marshal (Tom Wopat), gather outside. When the Marshal demands he give himself up, he first exacts the concession that no one will shoot him on sight; that he’ll get a fair trial before being hanged by the neck. The Marshal reluctantly agrees. So he walks outside into the gauntlet of guns, unarmed but with a story. Their sheriff? Bill Sharp? He isn’t who they think he is. He’s a wanted man, with a bounty on his head, and Schultz is a court-appointed bounty hunter, and that’s why he killed him. He has the piece of paper in his pocket to prove it. “In other words, Marshal,” he adds, trumping everyone, “you owe me $2,000.”

Nice. And the main reason it works is because it’s true.

The mostly false story of the Mandingo slaver

In this manner, Dr. King Schultz and Django move through the Midwest and South telling stories, killing men, collecting bounties. Sometimes the stories aren’t enough, as when Django kills two of the Brittle brothers in the presence of Big Daddy (Don Johnson), who then gathers a posse, an early version of the Ku Klux Klan, to kill the nigger and the nigger-loving German. But King knows when his stories aren’t enough and he’s ready for them, with dynamite (patented in 1867, but whatever). The purpose of the Kluxers is comic relief. Before they ride, they complain about the hoods with the eye slots. How they can’t see. How they can’t breathe. Can they just not wear them? It’s the funniest part of the movie.

King even tells Django a story around a campfire. It’s the story of Brynhildr. It resonates because Django’s wife, who was whipped by the Brittle brothers and resold into slavery, is named Broomhilda (Kerry Washington). She was raised by Germans, speaks some German. That’s an interesting coincidence, by the way. The slave that the native German bounty hunter needed to collect a bounty has a wife who speaks German. Here’s another: Schultz learns, by and by, that the slave he bought and freed also turns out to be the fastest gun in the South. Too many coincidences like these can get in the way of a good story. We begin to question the things we’re hearing or watching. Where was that chain gang of slaves going at the beginning of the movie anyway? How did Dr. King Schultz find them in the middle of the night in the middle of Texas? And how did he find them coming the other way? If he was pursuing Django, wouldn’t he be catching up to them? Too many coincidences make us wonder if the storyteller is a bad storyteller; or if he’s just lying to us.

The power of Schultz’s stories in the first half of the movie is that they’re true. He goes wrong—and you could say Tarantino goes wrong—when he begins to lie.

Schultz and Django, partners now, discover that Broomhilda has been sold to Calvin Candie, of Candieland (great name), in the deepest part of the South: M-I-S-S-I-S-S-I-P-P-I. How to get her back?

Schultz gives a quick reason why they don’t rely on some version of the truth. I forget what it is. I also don’t understand why they don’t use the story he uses in the end: He’s German; he misses speaking German; might he, perchance, buy the slavegirl who speaks German? Calvin Candie isn’t an unreasonable sort. He’s also a bit of a slave to Southern hospitality. I’m sure he would’ve acquiesced to this request for a fair (or unfair) price. Using this scheme, Schultz wouldn’t even have had to bring Django with him to Candieland. And since the heat between Django and Broomhilda is what tips off the house slave Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson), who alerts his master, leaving Django back in town, or up North, might have averted the bloodbath that follows.

But that’s the thing. Schultz, the storyteller, is interested in averting bloodbaths. Tarantino, the storyteller, is not. In fact, he needs the bloodbath or the movie isn’t a Tarantino movie. It’s just full of words. It’s not cool. A few years ago, in “Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation!,” a documentary about Australian exploitation movies, Tarantino said the following about how the low-budget thriller, “Patrick,” nearly influenced “Kill Bill”:

I always remember that actor. I thought he was amazing-looking in that movie with his eyes just wide open and everything, and in the original script [for “Kill Bill”] I had it written like that. Then I showed it to Uma and she goes, “I’m not going to do that,” and I go, “Why?” and she goes, “You wouldn’t have your eyes open like that if you were in a coma! That’s not realistic.” I go, “Actually I never thought was it realistic or not, it’s just Patrick did it, alright, and it looked really cool.”

That’s always been the problem with Tarantino. Given the choice between realistic and cool, he always goes for really cool.

The battle of the remaining storytellers

So Schultz concocts the false story, the made-up story, of wanting to purchase a Mandingo wrestler, while his companion, Django, a freed slave, is his advisor in the matter. Eventually they’re uncovered. The rest of the movie becomes, in a sense, a battle of the storytellers.

First, Calvin Candie, discovering the subterfuge of Schultz and Django, doesn’t just go into the dining room with guns cocked; he goes in there with a story. It’s a story meant to reassert white superiority over the Negro. It involves a hammer, and a skull, and dimples in an area of the skull, and it ends with the hammer coming down.

After Candie and Schultz have been killed, our next storyteller is Stephen. By this point, Django has killed many white folks, which, yeah, you don’t do in M-I-S-S-I-S-S-I-P-P-I, and the question becomes what to do with him. The white folks have the same old ideas: lynching, castration, dogs. But Stephen has a thought. Lynch Django and he becomes a legend for everything he’s already done. But force him to live out his days in subservient toil, for, say, the LeQuint Dickey Mining Co. of Australia, until he dies old and frail and useless, well, that will lessen his legend. It will change the trajectory of his story. That’s how he even puts it to Django. He imagines the day when Django finally keels over from overwork in the mines and tells him, “And that will be the story of you.”

And it might have been. But “Django Unchained” isn’t just a revenge fantasy. It is, to use the German, a bildungsroman, in which our protagonist, Django, mentored by Dr. King Schultz, moves from the darkness of slavery and into the light of absolute, fuck-you freedom. From Schultz, he learns about bounty hunting and guns. He learns how to dress and how to kill. And by the end, he’s learned how to tell a story, too. Sold to the Aussies, he uses this power. He tells them they’ve been lied to by the folks at Candieland, who claimed Django was a slave; he tells them that there is bounty-hunting wealth beyond imagination back at Candieland if they just want to go back and claim it. This story has the advantage of being mostly true, and the other slaves, too dim and scared to lie, corroborate it. So the Aussies, straight out of an Ozploitation movie, set Django free and die. And Django returns to rescue Broomhilda and put a final end to Stephen, the house nigger, and to Candieland itself. He blows it up, puts on his sunglasses, and rides off into the sunset with his girl.

And that, says Tarantino, is the story of him.

The story of the storyteller

So what’s the story of Tarantino? It’s changed over the years, hasn’t it?

First, it was the story of the videostore clerk who became a hot screenwriter and director. Then it became the story of the auteur who employs favorite or forgotten actors. He started with Travolta in “Pulp Fiction,” moved onto Pam Grier and Robert Forster in “Jackie Brown,” and never really stopped. “Django Unchained” gets its name from the great spaghetti western “Django,” starring Franco Nero, so we get Nero, of course. He’s the dude at the bar at the Cleopatra Club who asks Django how his name is spelled. “The ‘D’ is silent,” Django says. “I know,” Nero says with a proud smile. Another cool, false moment for QT.

Other forgotten actors in “Django” include the aforementioned Don Johnson, Tom Wopat and Don Stroud; Dennis Christopher of “Breaking Away” as the Cleopatra Club owner; Lee Horsley of TV’s “Matt Houston,” and Ted Neeley, Jesus Christ Superstar himself, as one of the trackers whose hounds tear apart the runaway slave d’Artagnan. Neeley hasn’t acted on screen since 1985.

More recently, though, the story of Tarantino for me is the story of the auteur who never really lived up to the promise of “Reservoir Dogs” and “Pulp Fiction”; who, when given the choice between realistic and cool, always goes with cool, no matter how false it may be. He needs to learn the lesson of Dr. King Schultz. When you tell your story, try to make it more-or-less true. Make it so true that you can end it, and trump your enemies, with a piece of paper rather than a gun. Because in the end that’s cooler.

—January 1, 2013

© 2013 Erik Lundegaard