Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

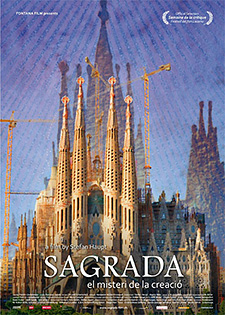

Sagrada: el misteri de la creació (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Of all the people Stefan Haupt interviews in his 2012 documentary on the history and majesty of La Sagrada Familia, the unfinished Barcelonan basilica designed by one of the world’s great architects, Antonin Gaudi (1852-1926), the interviewee who lives up to the doc’s subtitle, “el mistiri de la creació,” is Etsuro Sotoo, a Japanese sculptor.

Early in the doc, Sotoo talks to us matter-of-factly, in accented Spanish, about his work on one of the basilica’s three grand facades, and keeps referencing “the master.” One assumes he means Gaudi. He doesn’t. He’s talking about the stone. He calls sculpting a conversation with the stone. “Without the permission of this stone, this master,” he says, “I can’t do anything.”

I love this guy.

Much of the rest of the story of Sagrada’s creation—its starts and stops—isn’t a mystery at all. It’s same old: war, politics and money.

What’s the hold-up?

The doc begins with hardhats working like any construction crew on any tall building in any metro area. But here they’re helping build beauty. You think, “Well, you can’t feel too shitty at the end of that day.”

Work on the structure actually began on March 19, 1882, with a different chief architect. Gaudi took over a year later with grander designs. By the time he died, in a traffic accident in 1926, only one façade had been built. Then the Spanish Civil War intervened. Then Franco and fascism. There was a hiatus, or a near-hiatus, of 40 years: 1936 to 1976. The American part of me forgets that sometimes. “Oh right. That sort of thing does get in the way, doesn’t it?”

Lack of money was an even greater problem. Then there were the post-Franco controversies. Which was the greater insult to Gaudi: continuing the work even though his original designs had been burned in 1936; or leaving his great gift to God, and to us, unfinished? In a way, the Catalans split the difference: continuing with a chief sculptor, Josep Subirachs, who had sided with “unfinished.” In his sculptures, Subirachs acceded nothing to Gaudi. Where Gaudi opted for curves and flow and naturalism, Subirachs chose harsh, rigid right angles and blocky shapes. His depiction of the crucifixion on the Passion façade leaves Jesus nude and his head unsculpted. It’s just a block. It looks like the Son of God is wearing a bag over his head. He’s the Unknown Christ.

Sotoo, the new chief sculptor, is the opposite of all of this. Instead, he moved to Barcelona, learned Spanish, and even converted from Buddhism to Roman Catholicism in order to better see as Gaudi saw. That was his goal. By subsuming himself in this manner, interestingly, he stands out more. By not demanding his own individual artistic expression, he becomes the most memorable individual we meet.

What’s the rush?

Controversies continue. In 2010, for example, a tunnel for a high-speed AVE train between Barcelona and Paris began construction 30 feet beneath La Sagrada Familia. Is it a danger to the structure? Will it be over time? The tunnel seems incredibly short-sighted to me, given the disaster that could occur, but that didn’t give enough people pause. Of the pace of Sagrada’sconstruction, Gaudi famously said, “God is not in a hurry.” Not true for the rest of us.

At least Sagrada is funding itself now. It’s a huge tourist destination: three million visitors a year, the doc tells us. For some reason, that didn’t sound like much to me until I did the math: eight thousand a day. Since Sagrada is open an average of 10 hours a day (nine in the winter, 11 in the summer), that’s 822 visitors per hour, or 13.6 per minute. Which means every five seconds, someone from somewhere is entering La Sagrada Familia.

You enter the doc, “Sagrada,” hoping it soars as high as the basilica, Sagrada, but that’s a tall order. In the end, we get a fairly straightforward presentation. It gives us this foreman, that designer, this priest, that maker of stained glass. It’s not bad, but it’s all rather pedestrian.

Occasionally, though, it soars. It can’t help it. Just look.

—September 23, 2014

© 2014 Erik Lundegaard