Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

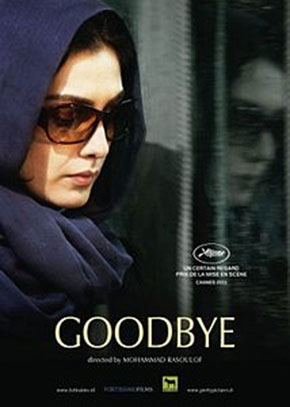

Goodbye (2011)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The first word spoken by the protagonist of “Goodbye” is hello. Noora (Leyla Zareh) is an Iranian lawyer whose license has been suspended, and who, we learn by and and by, is pregnant and trying to leave the counry. The lawyer she’s hired has helped others escape, and he has a plan for her. She’ll give a talk abroad and then just walk away. So why do we feel the weight of her ambivalence? Why does she talk of abortion when her pregnancy, she’s told, will help her escape? Is she ambivalent about leaving Iran or being pregnant? Answers come by and by.

“By and by” is the key to “Goodbye.” Writer-director Mohammad Rasoulof is a fan of the long, static shot, with characters moving into and out of frame, and he directs Zareh as if she’s close cousin to Catherine Deneuve at her most aloof and unknowable. If Hollywood movies are avalanches of action and suspense, “Goodbye” is a slow drip of unreliable information. Where is her husband? Is he working in the fields in the south? Is he a journalist working against the regime? Is he a former journalist the way she’s a former lawyer, and now he’s working in the fields in the south? Either way, it beats her current job. In her dingy, gray-blue apartment, she glues together pretty boxes that a man picks up once a week.

Most of the time, though, she’s waiting, and we’re waiting out her waiting. She goes to this office, that office. She feeds her pet turtle. She gives him water. She takes him from his atrium and puts him in a pan of shallow water from which he tries to escape. She puts up a flimsy barrier of newspaper around the pan—a kind of metaphor for media blackout?—and he escapes anyway. Shame. That turtle was the most dynamic part of “Goodbye.”

Background: In 2010, Rasoulof was arrested in the same raid that nabbed fellow Iranian director Jafar Panahi, who went on to make “This Is Not a Film,” with which “Goodbye” shares much. Panahi put himself at the center of his film but otherwise both movies are Kafkaesque explorations of authoritarian limbo. Both characters are accused and await sentence or escape. Panahi’s film, being real, ends more ambivalently.

Noora’s ambivalence, it turns out, is not about leaving Iran. She often goes to the rooftop of her apartment building for a cigarette, and in the background we see airplanes taking off. Despite the jet-engine noise, she doesn’t bat an eye. She doesn’t even look at them. She betrays nothing. But this is what she wants: escape; goodbye. Near the end of the film, she tells one of her husband’s colleagues, sitting on a small park bench, “If one feels a foreigner in one’s own country, it’s best to leave it and be a foreigner in a foreign land.” Great line.

No, the weight of her ambivalence is about her baby, who has been diagnosed with Down Syndrome. She’s not sure whether to keep it. Then she’s sure she wants to keep it. After that, everything else is machination. The timing must be right. To get the money to pay off the lawyer who has her passport, she needs the deposit on her apartment. To get the deposit on her apartment, she needs to vacate a few days early. To get a hotel room in Tehran, she needs a husband. She’s like the pet turtle in the shallow pan: barriers, large and small, continue to confront her.

No, the weight of her ambivalence is about her baby, who has been diagnosed with Down Syndrome. She’s not sure whether to keep it. Then she’s sure she wants to keep it. After that, everything else is machination. The timing must be right. To get the money to pay off the lawyer who has her passport, she needs the deposit on her apartment. To get the deposit on her apartment, she needs to vacate a few days early. To get a hotel room in Tehran, she needs a husband. She’s like the pet turtle in the shallow pan: barriers, large and small, continue to confront her.

The night before her flight, at the Shiraz Hotel (Rasoulof was born in Shiraz), she leaves word with the front desk for a wake-up call and taxi to the airport. A mistake? We watch her cut bread for the journey. She sleeps, and dreams of a Down Syndrome child, then wakes to a knock on the door. Earlier in the film we watched her apartment being methodically searched by plainclothesmen. This time we just hear them.

She: Yes?

Man: Open the door.

She [pause]: Who is it?

Man [pause]: Open the door.

She fetches a more formal veil to wear from her suitcase; and as she walks away and opens the door, the camera stays on the suitcase even as we hear the sounds of men arresting her and taking her away. Unfamiliar hands paw through her belongings and remove evidence. The final sound we hear is the screech of an airplane taking off—the one that doesn’t incude Noora. I thought of a spin on a Bob Dylan song: It takes a lot to laugh, it takes a plane to cry. The suitcase stays.

“Goodbye” is, I admit, a movie more interesting to write about than to watch. I almost nodded off several times during the screening. It’s a slow drip of a movie, a kind of Iranian water torture, and I wanted it to give me more. But I’m a spoiled moviegoer and a spoiled man. When Noora first says her famous line, about feeling a foreigner in one’s own country, I felt that it applied to me, too. I certainly felt similar during most of the Reagan and George W. Bush administrations. But my discontent is mild, and with my fellow citizens who elect such leaders, while hers is overwhelming and with leaders who allow no opposition voices. It’s the difference between “1984” (her world) and “Brave New World” (mine).

I kept thinking of a line from E.L. Doctorow’s “The Book of Daniel”; something Daniel’s father, Paul Isaacson (read: Julius Rosenberg), tells his young son about all of the injustice in the world. “And it’s still going on, Danny,” Paul Isaacson says. “In today’s newspaper, it’s still going on. Right outside the door of this house it’s going on.” This is current events as art.

The movie begins with a hello and it ends with a goodbye, but it’s not the goodbye we wanted. Noora doesn’t escape from; she disappears into. And it’s still going on.

—May 26, 2012

© 2012 Erik Lundegaard