Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

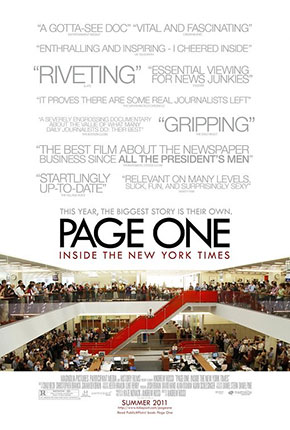

Page One: Inside the New York Times (2011)

WARNING: INK-STAINED SPOILERS

I was talking about this documentary with Evan, the friend who recommended it, and admitted it made me realize why I never became a true journalist. It wasn’t because I wasn’t curious enough or a good-enough writer or a fast-enough writer when I needed to be. It’s because I wasn’t tough enough.

In the doc you watch David Carr, media columnist for The New York Times, take on various bombastic elements and shut them up. He stares them down, calls them on their bullshit, then moves on. Even when I’m able to do the first two things, I don’t move on. I allow the first two actions to linger and infect the surroundings. Carr, who looks like nothing much, Bilbo Baggins’ after a bad night, with a hoarse voice and a skinny neck and a wide middle and a face that seems permanently bent toward the ground—that seems to have trouble looking up—is able to cut so surgically through situations that there’s actually little bleeding. It’s like those scenes where Zorro takes a swipe at a candle and it doesn’t move, causing the villain to laugh at Zorro’s ineptitude and anticipate his demise. Which is when Zorro holds up the tip of the candle, or pushes the tip off with his sword, or stomps on the ground and the candle crumbles to bits.

That’s what Carr is like. The other guy laughs at his ineptitude and then David stomps on the ground and the dude’s argument crumbles to bit.

As both Evan and I admired this ability of Carr’s, and lamented our own ability to cry bullshit in social situations, he added, “You know what I could use? A David-Carr-in-the-box. So when I get in those situations, I can take out my David-Carr-in-the-box, and just, you know, pop. Let him loose.”

I agreed. We could all use a David-Carr-in-the-box. The New York Times should get on that. Talk about your revenue streams.

Who’s afraid of the big bad Wolff?

“Page One: Inside the New York Times” also reminded me, of course, of something I lamented daily about two years ago: the death of newspapers; the death of print. I’m in the business, an offshoot of journalism, a small, momentarily protected niche, but I haven’t worried about the death of investigative journalism much in the last year. I’m not sure why. The problem certainly hasn’t gone away.

It’s a seemingly insurmountable problem. Investigative journalism, done right, is expensive, and in the past was paid for by two revenue streams: ads and subscribers. The Internet, our new, more democratic printing press, has cut into, if not obliterated, both of these. Craig’s List killed classified ads, online ads pay a fraction of print ads, and online readers, those spoiled, spoiled children, have been conditioned to expect content for free.

There’s also the problem of audience. Investigative journalism is not only tough to do but tough to read. It takes work. How much better to go to an aggregate/opinion site/blog that boils it all down and also gives you pictures of celebrities in bikinis or with baby bumps or in the midst of divorces. How much easier to just be distracted. How much more fun.

One of the pivotal and most satisfying scenes in “Page One” occurs about halfway thorough, at a debate by a group called “Intelligence Squared,” which, for its topic of the night, raises a purposely provocative one: GOOD RIDDANCE TO THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA.

Carr, the schlub, gets to represent the mainstream. His opponent, at least as far as we see in the doc, is Michael Wolff, founder of newser.com, an aggregate site. Wolff looks a bit like Alvy Singer’s balding, viral man. He seems fit, and tough, and his bald head gleams like he’s from the future. And he brings us a message from the future:

What you’re going to hear tonight is that the media is necessary for the commonweal. An informed citizenry is what this nation is about. That is self-serving crap. The New York Times is a good newspaper—sometimes... But after that it’s off the cliff. It’s oblivion. The news business in this country is nothing to be proud of. The media is a technology business. That’s what it is. That’s what it has always been. Technology changes, the media changes.

Carr obliterates him. He begins politely by holding up a print copy of the home page of Wolff’s site. “Newser is a great-looking site,” he says, “you might want to check it out. It aggregates all manner of content. But I wonder if Michael’s really thought this through. Get rid of mainstream media content...” Then he holds up that index page without the aggregated mainstream articles. It’s mostly holes. It barely exists. He peeks through it at the audience, which is applauding, and says, “OK, go ahead.”

Great scene. It not only reveals Wolff’s hypocrisy—how he’s making money off the very thing he’s disparaging—but it reveals the hypocrisy of the Web. Much of the Web simply repurposes someone else’s work. The Web doesn’t care for originality or accountability; and it’s creating a society that doesn’t care for originality or accountability.

Is the Times necessary because it’s good?

At the same time ... OK, Carr makes a salient point. What happens when mainstream sites like the New York Times, which still drive much of the discussion on the Web, disappear? What replaces them? Don’t we need vegetables? Don’t we need meat? Or are we just going to keep popping the content equivalent of Milk Duds in our mouths?

But it doesn’t address all of Wolff’s points. From the above, two remain:

- The Times says it’s necessary because it’s good but Wolff says it’s not that good so it’s not that necessary. So: Is the Times good?

- Media means technology. Technology changes. You can gripe all you want but it’s going to change.

To the first point. The Times has its weaknesses. It’s a serious paper—it’s not sensationalistic like most of the mainstream media—but it has a love for, or at least a trust of, the institutional voice. The doc treats Judith Miller’s reporting on WMDs like it’s an anomaly but that was based upon institutional trust—upon getting access to the institutional voice and printing it—and the Times does this all of the time. Its coverage of Hollywood, say, is almost always from the studio perspective. Its coverage of business is almost always from the Wall Street perspective.

And in politics? It gets played. It assumes an opposition voice, no matter how marginalized, provides balance. It assumes that an institutional voice is legitimate even if it’s in the middle of a lie. It won’t call a lie a lie. Public Editor Arthur S. Brisbane’s recent column, “Should The Times Be a Truth Vigilante?,” is indicative of this attitude. Brisbane wrote:

[Some readers] fed up with the distortions and evasions that are common in public life, look to The Times to set the record straight. They worry less about reporters imposing their judgment on what is false and what is true.

Is that the prevailing view? And if so, how can The Times do this in a way that is objective and fair? Is it possible to be objective and fair when the reporter is choosing to correct one fact over another?

That sound you heard was people around the country exclaiming, “WTF!?!”

The answer to Brisbane’s dilemma is obvious. If a public figure says something demonstrably false, you call him on it, and as high up in the article as possible. If a public figure says something harder to disprove (or prove), but without evidence, then that’s your story: X ACCUSES Y OF Z: PROVIDES NO EVIDENCE. It’s less choosing to correct one fact over another than printing what facts we have. And if an institutional voice proclaims factual what is not factual, that’s your story. Objectivity is not stupidity.

But the doc doesn’t own up to this or any weakness in the Times. It’s basically saying: we’re good so we’re necessary. So please don’t kill us. For your own good. It's saying, as Carr said to the Intelligence Squared audience, “OK, go ahead.”

The Times they are a changing

For the most part, I agree. But then we get into the second of Wolff’s unaddressed points: It doesn’t matter if the Times is good or not. Its model, the printing press, is now obsolete. Everyone has a printing press. Most everyone’s printing. Or posting. Or uploading. The Times used to have to compete against however many newspapers in New York City, and maybe two or three nationally, and another one or two internationally. Now the competition is everyone and everywhere. Even this little ol’ site is competition. You’re reading it, after all, instead of the Times. Wastrel.

“Page One” is a fine-enough doc, particularly when David Carr’s onscreen, but, in journalistic parlance, it misses the story. Can one support serious investigative journalism in the digital age and on a digital budget? If not, what replaces it? And what becomes of our misinformed and malinformed and don’t-want-to-be informed citizenry—and, by extension, our democracy—then?

—March 4, 2012

© 2012 Erik Lundegaard