Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

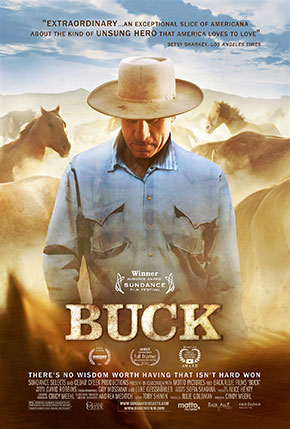

Buck (2011)

WARNING: SKITTISH SPOILERS

Of Buck Brannaman, the subject of Cindy Meehl’s documentary “Buck,” and a man who spends 40 weeks a year traveling the country giving seminars on horses, one of the talking heads in the doc says, “God had him in mind when He made a cowboy.”

Buck certainly fits some of our preconceptions. He doesn’t talk much, particularly for someone who talks for a living, and he’s got an aw-shucks manner, particularly for someone who’s often in the center ring. He ambles rather than walks. He’s married with children but spends most of his days alone and carries that solitude with him. He knows horses, and through horses, people. He does rope tricks. He drinks his coffee black. He’s named “Buck.”

He also expands our definition of what it means to be a cowboy.

“I was watching ‘Oprah,’” he begins at one point, then pauses and manages a crooked smile. “I don’t know if I should admit to that.”

He “starts” horses, he says, he doesn’t break them. His approach is discipline without punishment, empathy without sentimentality. Horse people come to his seminars skeptical and leave stunned. Their tough love doesn’t work. Their soft love doesn’t work. But Buck gets in the ring and in five minutes their horse is following him around like a dog. He takes an unfocused horse and focuses him. He takes a skittish horse and calms him. The advice he gives goes beyond horses.

- “Make it difficult for the horse to do the wrong thing and easy to do the right one,” he says.

- “You can't just love on them and buy them lots of carrots. Bribery doesn't work with a horse. You'll just have a spoiled horse,” he says.

- “When you’re dealing with a kid or an adult or a horse, treat them the way you’d like them to be, not how they are now,” he says.

He has a great, empathetic description of what a horse is allowing you to do when you ride it. On his back? By his neck? That’s where he’s attacked. So when you climb on him to ride him, he’s trusting you enough, or respecting you enough, to allow you into this vulnerable spot. Respect that.

He talks about the different kinds of feel—by which he means communication. “Everything’s a dance,” he says. “Everything you do with a horse.”

Horses can sense, I’m sure, his gentle spirit, as surely as Robert Redford, another talking head in the film, sensed it. They met when Buck was an advisor on Redford’s film “The Horse Whisperer.” Redford talks about filming a particularly difficult scene in which the film’s injured horse is supposed to go up and nuzzle the daughter, played by a young Scarlett Johansson, on cue. It’s a trick horse, a trained horse, but not a horse affiliated with Buck, and they spend all day and can’t get the shot. Then Buck suggests his horse. They get the shot in 20 minutes.

So who is this real-life horse whisperer? Someone who starts rather than breaks horses? He’s someone who was almost broken himself.

“When something is scared for their life, I understand that,” he says.

I wouldn’t be surprised if I saw Buck some Saturday morning in 1970. He and his brother, rodeo stars who could do rope tricks blindfolded, were in a “Sugar Pops” commercial back then. And like another child star back then, Michael Jackson, Buck was controlled by, and abused by, his father. “He beat us unmercifully for not putting on a perfect performance,” Buck remembers. Buck’s mother would sometimes act as a barrier between the rage of the father and the vulnerability of her sons, but she died when Buck was young and he knew then that he was truly alone in the world. We get this story by and by. How a gym teacher in high school saw the marks on Buck’s back. How he alerted the authorities. How Buck wound up with a foster family in Montana that was raising 23 kids, and the father immediately gave him gloves and put him to work on the farm, and how that’s just what Buck needed. A purpose. The gloves were so special he didn’t even put them on when handling barb wire.

Buck Brannaman is a great subject for a documentary but “Buck” isn’t a great documentary. It’s a good documentary, a worthy documentary, a movie I’d recommend you see rather than whatever tentpole crap Hollywood is trying to erect this week, but it doesn’t feel as dense or as deep as it should. We get various scenes of Buck calming and controlling horses, but near the end we get a horse, in Chico, Calif., I believe, that can’t be calmed. It’s a spoiled horse, a mean horse, and Buck manages to work with it for a time in the pen; but when he’s away the horse attacks another cowboy, bites him in the head, draws blood, and it’s decided to put the horse down. Buck returns. He helps load the horse onto a truck. He chastises the horse’s owner. The horse’s owner talks to the camera about having to put her horse down. Then she and her horse leave.

That’s it?

Hollywood, I suppose, has conditioned us for a better ending—isn’t Buck supposed to save the day, as cowboys have been doing in movies since the silent era?—but the doc raises our expectations, too. Buck helps horses. That’s what he does. Horses with people problems. That’s what this horse is. So why is this horse beyond help? Why doesn’t he talk to us about this horse? It’s the emotional climax of the film but it’s not tied enough to the subject of the film. Meehl needed to tie that knot tighter.

And where’s his brother? We see photos of the two together, as adults, but no word from or about him.

Even so, see “Buck.” As he says about his methods: “It’ll make you better in areas that you didn’t think related to horses.” Bring the kids.

—July 28, 2011

© 2011 Erik Lundegaard