Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

The Housemaid (2010)

WARNING: REVENGE-SERVED-HOT SPOILERS

Im Sang-soo’s “The Housemaid” (2010) is based upon Kim Ki-young’s “The Housemaid” (1960), a classic Korean film that was only recently discovered by cineastes in the West. Both “Housemaids” are about the horror that results when a new maid has an affair with, and a pregnancy from, the man of the house; but there are two major differences in terms of story.

In the original, the family is middle-class. They’ve finally bought a home, which they’re fixing up, but the husband has to work two jobs and the wife takes in sewing. At the same time, they’re happy. It’s the housemaid, a sexually predatory femme fatale, who instigates the affair, and ultimately destroys both happiness and family. Basically: it’s how a singular, outside corruption destroys a collective, familial innocence. Meaning it’s a story as old as the Garden of Eden and as oft-told as “Fatal Attraction,” “The Hand that Rocks the Cradle,” and the tabloid exploits of Angelina Jolie.

In Im Sang-soo’s new version, the family is fabulously wealthy and powerful, and their home is vast, clean and cold, with an elongated fireplace that seems to produce no heat. The housemaid, Eun-Yi (Jeon Do-yeon), is an innocent, and it’s the husband, Hoon (Lee Jung-Jae), who instigates the affair. Basically: it’s how a singular, outside innocence is destroyed by a collective, familial corruption. Meaning it has more in common with most westerns than it does with Kim Ki-young’s original.

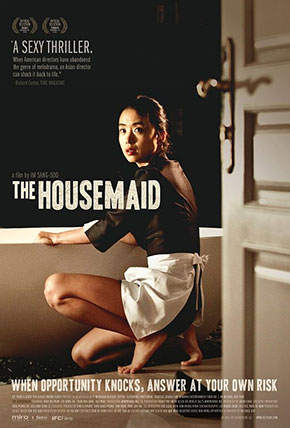

The housemaid as outside malevolence who destroys a familial innocence (above, in the 1960 original), and as an outside innocent who is destroyed by familial malevolence (in the 2010 remake).

The new “Housemaid” begins in almost cinema verite fashion. On what looks like a Friday night in Seoul, an unnamed and unknown woman moves out on a four-story ledge as, below, vendors prepare food, girls frolic in a second-story danceteria, and couples wonder where to go for the evening. A minute later she jumps. It causes a minor stir but life, such as it is, goes on. One of the vendors, Eun-yi, with her friend, visits the scene of the crime: a chalk outline stained in blood. Is this what spurs her to improve her position and get the housemaid job? This reminder of the shortness of life? She doesn’t know it, but looking up to the height from which the woman jumped, she’s looking into her own future.

We’re introduced to the family piecemeal. Here’s the older housekeeper, Mrs. Cho (a glorious Yoon Yeo-jeong), who is herself so entitled she enters Eun-yi’s apartment without permission before hiring her. Here’s the young mother, Hae-ra (Woo Seo), with huge, swollen belly, doing pregnant yoga and reading picture books on Matisse. Here’s the young, stoic daughter, Nami (Ahn Seo-Hyun), acting less childlike and more knowing than Eun-yi, who dotes on her. Finally, here’s the father, Hoon, or Mr. Goh, arriving late, walking before two bowing associates, drinking his expensive red wines and playing his Beethoven sonatas.

Is there a correlation between the westernization of the Gohs and their corruption? Have they lost their Koreanness and thus their souls? Jean-Michel Frodon of Cahiers du cinéma compared the original director, Kim Ki-young, to Luis Buñuel. Is Im Sang-soo, in this regard, the Korean Olivier Assayas?

We know what’s going to happen, of course. We’ve seen the poster—Eun-yi crouched before a bathtub, all bare legs and apron, something breathless in her face—and we’ve read the synopsis, full of words like “erotic” and “steamy.” That’s what draws us in. That’s why we’re in the audience. But those adjectives are slightly misleading. At a mountain resort, yes, Mr. Goh enters the servant quarters with a bottle of wine, demands Eun-yi reveal her body, feels her up, demands and receives oral sex. But nothing is particularly “steamy.” This is a cold thriller. It’s filmed cold, its people are cold, they live in a cold mansion. Dark blues and steel dominate. The first words in the movie, in fact, are “It’s cold, where should we go?” Only the revenge at the end is served hot.

A question: If Eun-yi is truly innocent, why does she go along with the affair? Her own answer, to her friend, is compartmentalization. She tends to the Mrs. during the day and the Mr. during the evening. Mr. Goh, meanwhile, deals with any romantic thoughts she might mistakenly have by tucking a check into her shirt. I pay for this, too.

We also know the affair will blow up—badly. The question: Who will be ally to Eun-yi and who an enemy? Or is she surrounded by enemies?

Mrs. Cho is the wild card. Early on she seems as dismissve as the family; but then we get a great scene in the bathroom of the servant’s quarters. Eun-yi is on the toilet while Mrs. Cho, cigarette going, holds forth from the bathtub. She calls the job RUNS (Revolting, Ugly, Nauseating and Shameless), and counsels Eun-yi away from it:

“You get up in the morning and think about what you have to endure and [grimaces] it makes your gut hurt. But what can you do? Just breathe in deep and transform into a cold stone.”

Mrs. Cho already knows about the affair; and it’s while eyeing Eun-yi in the bathroom that she figures out she’s pregnant. What to do with this information? She goes to Ha-rae’s mother (Park Ji-young), even more beautiful than her daughter, who is full of distant, flutey compliments about Mrs. Cho’s son becoming a prosecutor, but who proves to be the most villainous element in the story. She knocks Eun-yi off a ladder, and watches her fall two stories to the cold, marble ground. She is never far from her daughter’s ear, into which, Lady Macbeth-like, she pours her calm, poisonous thoughts. “I should’ve pushed her from someplace higher and ended things,” she says matter-of-factly. It’s the matter-of-factness that’s scary.

Ha-Rae fixates on the affair and its various betrayals (“with a common maid,” etc.), but her mother sees the baby as the real problem. It gives Eun-yi power, makes her a rival, almost an equal, and they can’t abide that. Eventually they confront Eun-yi, who is now aware that she’s pregnant, and give her money for an abortion; but Hae-re, eyes opening, recalls the way Eun-yi talked baby-talk to her own swollen stomach, and figures Eun-yi will want the baby. The poisoned thoughts of her mother become literal poison, which she slips to Eun-yi, which induces a miscarriage. It happens in the bathtub. “No, don’t do this,” Eun-yi cries as she tries to hold it all together. “No, baby!” It’s a heartbreaking scene.

Now the family is through with her but she’s not through with them. “I can’t get it out of my head,” she says later. “What happened here. It’s so horrible.” So she does to them what they did to her. She creates an image so horrible they can never get it out of their heads.

“The Housemaid” is melodrama, and occasionally over-the-top, but it’s anchored by great performances, including Jeon, whose Eun-yi is, sweet, childlike, and slightly off throughout, and Yoon’s Mrs. Cho, whose stoic demeanor hides, not a secret smile for her employers, but a secret hatred. (Yoon, recently seen stealing the show in “The Actresses,” also played the lead in Kim Ki-young’s second housemaid film, “Woman on Fire,” in 1971.)

Woo, meanwhile, manages to coat Ha-Rae’s nastiest lines with a topping of sweetness. When she slaps Eun-yi for the affair without mentioning the affair, and Eun-yi apologizes for the affair without mentioning the affair, she comes back with a faux innocent, “For what?” She wants Eun-yi to say it. She can’t forgive Mrs. Cho, either, for going to the mother rather than her with the bad news, and for the rest of the movie wears her down. “Mrs. Cho,” she says in her dreamy, singsongy voice, “why are you chattering on late at night with that annoying voice of yours?”

Ultimately, for all its “erotic” and “steamy” qualities, this is a movie about class, and how the very rich are different than you and me—although Mrs. Cho would probably flip that cause-and-effect order. “Scary people,” she says at one point. “Probably why they’re so rich.”

The epilogue is a dreamy sequence right out of David Lynch, as the Gohs, seemingly mad, celebrate Nami’s birthday outside in the snow, with champagne, Hollywood art and English. No one speaks Korean. Their corruption is complete. They are homeless now.

—February 22, 2011

© 2011 Erik Lundegaard