Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

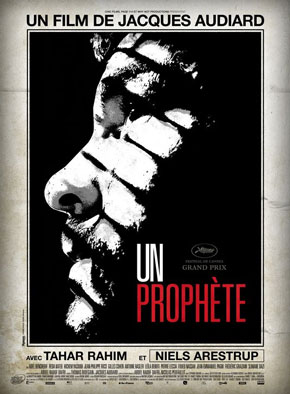

Un Prophete (2009)

WARNING: DEER-IN-THE-HEADLIGHTS SPOILERS

“The idea is to leave here a little smarter,” Reyeb (Hitchem Yacoubi) tells Malik (Tahar Rahim), as the two sit on the edge of his prison bunk and Reyeb stirs his coffee. Reyeb has just found out that Malik, his fellow Muslim, is illiterate, and he’s acting solicitous toward him—suggesting he can always learn to read, telling him he’ll give him some books—even as he’s anticipating a blow job. Instead he gets his throat slit. Guess the joke’s on him, right? Guess he left there a little smarter.

But he doesn’t leave. He remains in Malik’s life—a palpable, matter-of-fact symbol of guilt—and his words linger. And after six years Malik will leave there a whole lot smarter than when he entered. He will leave a prophet. It’s prison as a means to both worldly and spiritual redemption. Kids, don’t try this at home.

“Un Prophete,” which was nominated for 13 Cesars and won nine, including best picture, director (Jacque Audiard), actor (Rahim), supporting actor (Niels Arestrup), writing, editing, and cinematography, is both gritty and uplifting, full of lessons of realpolitik and the unknowability of dreams and life. It’s a movie for anyone who thought nothing more could be done with the prison drama or the gangster life. It’s a film we will still be watching in 50 years.

Malik’s life begins when he enters prison. He has nothing but the scars on his face and the 50-euro note he tries to hide in his shoe; it’s found and confiscated. He’s stripped, shaved, given a pillow and a metal tray and a new pair of tennis shoes. In the prison yard, alone, the shoes are big and white and seem to gleam, and a second later he’s attacked and his shoes are taken. He gives back—he attacks his attackers—but gets beaten down again. The odds aren’t good. He’s alone with six years to go.

He might not have made it if Reyeb hadn’t shown up. The prison is divided between Corsicans, who are few but control the guards, and Muslims, who are many but control nothing, and Reyeb, about to testify in a trial against a Corsican, is targeted by prison don Cesar Luciani (Arestrup), whose boss, Jacky, has given him 10 days to kill the snitch. Easier said. Cesar moves through the prison with relative ease but he doesn’t control the Muslim section. Then he hears that Reyeb asked this new kid to suck him off, and, in the prison yard, he makes Malik an offer he can’t refuse: Kill Reyeb or I kill you.

We later learn that Malik didn’t have much of an upbringing. When asked if he spoke French or Arabic with his parents, he responds, “I wasn’t with them.” When asked about school, he replies, “The juvenile center.” We have sympathy for him the way we would a stray dog. He’s scared and confused, but watchful, and back in his cell, after Cesar threatens him, he tells himself, “I can’t kill anyone.” He tries to contact the warden but the Corsicans hear and nearly suffocate him in a plastic bag, saying, “We run this place.” In the sewing shop he joins in a beat-down of a helpless prisoner, hoping to get tossed into solitary, but Cesar hears of this and beats him down. He’s trapped. He has to do this thing.

It’s the palpability of the act that gets you: less the Peckinpahesque spurting of blood from Reyeb’s neck than the goopy way blood and saliva mix as Malik pulls the razor blade from his mouth, where he’s involuntarily cut himself. It’s his careful extrication from the scene: stepping over the blood; placing the razor in Reyeb’s hand; scrubbing the blood from his shirt in the prison bathroom. It’s the disconnect one feels despite this precision. Malik hears someone screaming; he sees flames falling out of a prison cell. What is going on?

Prison life opens up for Malik afterwards. He receives cartons of cigarettes from Cesar (“You’re under his protection now”), and, taking Reyeb’s advice, he learns to read (“Canard: Ca-nard”), but he’s still isolated. The Muslims view him as a Corsican while the Corsicans disparage him as a dirty Arab. His main companion is the man he killed. In his dreams Malik wrestles with Reyeb, as if he were the Archangel Gabriel, and in the morning Reyeb is there, a physical presence. Reyeb is the one who sings “Happy Birthday” to Malik in Arabic on the one-year anniversary of his incarceration. He’s the one staring with him out his cell window as snow falls on the prisoners in the courtyard.

Life opens up even more when these Corsican gangsters, like naughty schoolboys, are separated by powers outside the prison. Perhaps feeling sorry for Cesar, Malik, eyes alight with his secret, reveals that he’s learned Corsican over the years and the conversations he’s been privy to. Cesar stares at him, then hits him. Because he senses the pity? Because he senses opportunism? Because his private conversations weren’t private and this dirty Arab is smarter than he realized? Regardless, he soon comes to rely on Malik more and more, but there is no corresponding sense of respect. He keeps treating Malik like a dirty Arab.

Bad move. Both inside the prison, and outside on work-leaves, Malik makes contacts and accrues power. He gets involved with Jordi, the Gypsy (Reda Kateb), who deals hashish. He becomes friends with Ryad (Adel Bencherif), who is the beginning of his entré into the suspicious Muslim prison community. He does his jobs, straddles both worlds, acts the professional. There’s an unaffected quality to him, an ingenuousness. “Why is an Arab working for the Corsicans?” he’s asked. “I work for who pays me,” he answers. One realizes after a while: He doesn’t lie. He’s polite, and professional, and doesn’t lie. The world he lives in expects lies and he disarms everyone with honesty.

His first work-leave is beautiful. After three years he’s finally out of prison, and as Ryad, who’s done his time, picks him up, Alexandre Desplat’s music, “La sortie,” wells up and overwhelms any attempt at conversation, as if the music were Malik’s emotions. He feels the wind on his face, the sun on his face; then he does a job for Cesar. He gets 5,000 euros to retrieve a Corsican gangster from a Muslim gang. Then he does a job for himself. He retrieves 25 kilos of hash stored by one of the Gypsy’s men. “Five thousand euros and 25 kilos of hash?” Ryad asks him, stunned, when they hook up at dusk. “All in one day?” You know that scene in “The Godfather” where Michael suggests killing the Turk? Where Michael essentially takes over? That’s this. Malik doesn’t respond to Ryad’s question. He simply tells Ryad what they’re going to do:

We get guys to stock and sell. We supply. We use convoys and buy at the source. The Gypsy has contacts. We need three big cars. Paris-Marbella in one night.

When Ryad objects, saying he’s never done this before, Malik responds, “What’s the big deal? Neither have I.”

What do we make of the prophet angle and Malik’s vision of the deer? To what extent do we compare Malik, the prophet, with the prophet Muhammad? Both are orphans. Both get involved in the merchant trade. Later in the film Malik will go into isolation, solitary, for 40 days and 40 nights, and emerge more powerful than ever. One can call him a Muhammadian figure the way one can call Luke in “Cool Hand Luke” a Christ figure. Elements of the ancient religious story are used to tell the tale of a modern prisoner.

Would things have turned out differently, less Oedipal, if Cesar had treated Malik with any kind of respect? Actor Niels Arestrup has a mane of white hair and fierce blue eyes, and initially one thinks of him as a Godfather type, a Don Corleone in prison; but as the movie progresses and one sees his prejudices, his betrayals, his smallness, one realizes he’s more like the Black Hand. He’s the classless oaf that needs to be overcome. It’s Malik who becomes the Godfather. At one point Cesar nearly puts Malik’s eye out, telling him, “People look at you and see me. Otherwise what would they see? Can you tell me?” The implication is that Malik is nothing without him, but the greater implication, which Cesar fears, or is perhaps too stupid to realize, is that Malik is becoming him. Returning to his cell, his eye damaged by Cesar, Malik promises himself “I’m gonna kill you,” just as, earlier, he’d promised himself, “I can’t kill anyone.” It’s the promises to himself that he breaks. He does kill, Reyeb and others, but he doesn’t kill Cesar. He does something worse. He renders him powerless. By the end their positions are reversed: Malik is the prison don, respected in his community, while Cesar is the weak, isolated man in the prison yard, beyond the circle of power. Beyond contempt.

The arc of its story is brilliant but it’s the details that stay with me—such as Malik’s first planetrip, sandwiched between two bored commuters, trying to get a glimpse of the sky out the window. He’s heading to Marseilles for a meeting, at Cesar’s behest, with Brahim Lattrache (Slimane Dazi—one of the many amazing faces in this movie), where, again, he’s the distrusted Arab courier, but where his vision of the deer saves his life. Afterwards the deer meat is washed in the Mediterranean, and Lattrache, eyeing him with new respect, is intrigued by this quiet, honest man who straddles cultures. “Let’s get sucked before you go,” he says, but Malik turns him down. “I’d like to stay on the beach,” he says. He wades out into the water. One senses he’s never seen the sea before. Back in the dark of his prison cell, he takes off his shoe, looks inside, upends it. Sand courses through his fingers.

I’ve seen this movie twice; I feel like seeing it again now.

—September 1, 2010

© 2010 Erik Lundegaard