Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

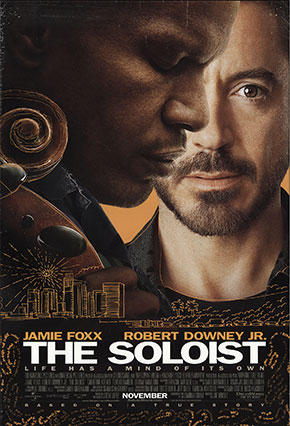

The Soloist (2009)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“The Soloist” is much better than I thought it would be when I sat down and not quite as good as I hoped it would be halfway through.

You probably know the story. You might’ve seen the “60 Minutes” segment on Steve Lopez (Robert Downey, Jr.), columnist for The Los Angeles Times, and one of his column subjects, Nathaniel Ayers, Jr. (Jamie Foxx), a homeless man he finds beneath a statue of Beethoven playing a violin with only two strings, and who, it turns out, attended Juilliard for two years in the ‘70s only to drop out when mental problems overwhelmed him. You might’ve read Lopez’s book about the experience. Hell, you might’ve seen the trailer for the film last fall, when the release date was November and Downey was being talked up for an Oscar nom. Then — boom — the film was pulled until April. “Uh oh,” I thought. Springtime for a serious film generally means death. It means it’s not good enough for fall.

I began to relax — began to realize how smart this film was — while hearing the early voiceovers from Downey: either writing his column on available scraps, recording it into a tape recorder, or, best of all, just writing it in his head as he’s walking. That’s it, isn’t it? That’s what we do. Even those of us who do this. At the same time, the voiceover moves the story along.

The film is remarkably integrated this way. It includes, among other riffs, dying newspapers, the homeless, Hurricane Katrina and Neil Diamond, but none of these things seems heavy or extraneous. Everything is integral. The flashbacks to Nathaniel’s earlier years don’t interrupt the story but continue or augment it. Yes, the movie borrows from “Amadeus” — using music to shut out the world — but why not? That’s what music does. That’s what art does. Even if you’re not a true artist, the point is to have the world fall away for a time. It keeps us sane.

Nathaniel is not. We get conversations like this, as Nathaniel and Lopez watch a plane fly overhead:

Nathaniel: Are you flying that plane?

Lopez: No, I’m right here.

Nathaniel: I don’t know how that works.

Nathaniel’s can’t separate things. Everything blends together in his mind. Even his words come in a stream-of-consciousness style reminiscent of Robin Williams’ comedy. One thing leads to the next leads to the next. Yet, for a time, this almost seems...right. Sane. For a time, everything seems part of the same big pattern — a pattern we can’t quite see — even though director Joe Wright (“Atonement”) keeps pulling back for overhead shots that let us take in, if not the pattern, then at least a pattern. The one we’ve created.

Is there any actor I’d rather watch think than Downey? Everything he does here has energy and intelligence. When he was a younger actor (and, yes, on coke), it was as if he tried to convey too much too quickly. He needed to age in order to slow down, in order to become palatable. We can understand him now.

His Steve Lopez is divorced, lives alone, has trouble with raccoons. He’s the other soloist, the man who keeps the world at a writerly distance. But he’s straightforward. When he finally reaches Karen, Nathaniel’s sister, and she asks why he’s interested in her brother, he doesn’t bullshit:

Lopez: I’m going to write a column about Nathaniel.

Karen: Why?

(pause)

Lopez: Because that’s what I do.

One column leads to another. Nathaniel’s true instrument is the cello, and an elderly woman who reads these columns sends hers. Of course Nathaniel can’t keep such an expensive item in his shopping cart — it could be stolen, he could be hurt or killed during the theft — so Lopez arranges to have it kept at Lamp, a nonprofit homeless shelter for the mentally ill. Initially Nathaniel objects to such a plan. When we finally see the place, so do we. The area outside Lamp is filled with refugees, like it’s a scene from a post-apocalyptic film, like it’s Los Angeles’ own Katrina, whose images flicker on background newsroom television sets. Lopez, more than Nathaniel, feels justifiably threatened there — among the mentally ill and drug-addicted.

There’s a great scene — maybe the best scene in a movie full of great scenes — where, once again, Lopez has made the difficult 30-foot, nighttime journey from Lamp offices to the safety of his car, and, inside, he breathes a sigh of relief. We’ve all been there. The camera holds on him and you wonder: Is someone going to attack him now that he feels safe? That’s a Hollywood staple. But no. The camera just holds. And a realization comes over him, some fundamental change, some silent recognition of responsibility or awareness of artificial boundaries (between, say, the car and the street), or maybe just an awareness of his own fears, and he gets out again and walks and searches — part of the crowd, now, not apart from it — and finds Nathaniel bedded down for the night and joins him. That’s another column. These columns lead to change, as the mayor promises $50 million for the homeless, and Lopez is later feted at a black-tie affair.

One wonders where the movie goes from here but I like where it goes. Two forces are at work within Lopez. He tries to help Nathaniel — getting him an apartment and a tutor — but he also wants to wash his hands of him. These seem like opposite forces but are actually part of the same impulse. By making him independent, he’s no longer responsible for him. Or he’s responsible for him only in the way that each of us is responsible for each other. Which is to say: Not at all.

When someone tells Lopez that he’s the only thing Nathaniel’s got, he responds, “I don’t want to be his only thing,” and, again, we know where he’s coming from. How much does he have to do? How much does he need to care? How much do we?

The script by Susannah Grant (“Erin Brockovich”) is full of great exchanges. “I don’t want to die in here,” says Nathaniel, freaked by his new apartment. “Don’t,” Lopez replies matter-of-factly. Earlier, outside Lamp, Nathaniel says: “I hope these children of God will be okay tonight. They’ll sleep and dream as humans do.” That’s nice. Don’t know if it’s Grant or in Lopez’s book, but it’s nice.

Great supporting cast — particularly Nelsan Ellis as the man at Lamp, and Catherine Keener, an editor at the Times, who, we find out, was once married to Lopez.

A few elements feel clunky, or political, only compared to the smoothness of the rest of the film. The ending, for example, includes both voice-over and revelation, but it needed only one of these.

Even so, “The Soloist” comes close to being a remarkable film. I want to close with another great scene that feels, without trying, without dotting its “i”s, to be integrating all of its parts. Keener is in her office as an offscreen higher-up is letting someone (her?) go while talking up the company’s “very good exit package.” Out her window she sees Lopez helping push Nathaniel’s shopping cart up a hill. They’re heading to the L.A. Symphony to listen to a rehearsal, but she doesn’t know that, she only knows what she sees. And she smiles this wistful smile. There’s great balance here: the comedy outside and the tragedy within; one man helping another while a company, part of a dying industry, lets another employee go. It doesn’t draw too fine a point — as I fear I might be doing — it just feels part of this big shifting pattern we all create. It’s worthy of Keener’s beautiful, wistful smile.

—April 24, 2009

© 2009 Erik Lundegaard