Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

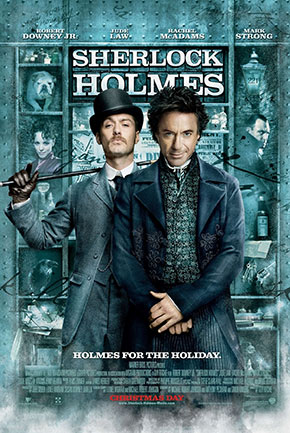

Sherlock Holmes (2009)

WARNING: THE SPOILERS ARE AFOOT

What if the character ‘Sherlock Holmes’ had been an original 21st-century creation of this film—of Guy Ritchie and Michael Robert Johnson and Anthony Peckham and Simon Kinberg and (whew) Lion Wigram, as well as Robert Downey, Jr., of course—instead of a 19th-century creation of Sir Athur Conan Doyle? How well would the movie have done with the critics and how well at the box office and how well with moviegoers after they’d plunked down their $10 plus and had a day, a week, a month, a year to mull it over?

I was mulling this over because, after two years of a self-imposed embargo, and as prep for the sequel, I finally watched “Sherlock Holmes” and for the most part enjoyed myself. It’s well art-directed, Downey, Jr. and Jude Law (Dr. Watson) have great chemistry, Rachel McAdams (Irene Adler) is always a pleasure, and the movie zips. It zips too much for me, of course, and for top critics, whose approval rating wound up at 56% on Rotten Tomatoes, but not too much for moviegoers in general, who spent $209 million on it in the U.S., $524 million worldwide, and who, having mulled it over, have given it a 7.5 rating (out of 10) on IMDb.com—akin, among Downey’s work, to “Wonder Boys,” and better than “Chaplin” (7.3) and “The Soloist” (6.7).

So what would’ve happened if this thing called “Sherlock Holmes” had been an original creation? I think its box office would’ve dropped, but not astronomically (no name recognition but everyone likes a roller coaster ride), its IMDb numbers would gone up (to 7.7 or possibly higher), because its top critics ratings at Rotten Tomatoes would’ve soared. I think the critics would’ve loved it.

“A cerebral roller-coaster ride!”

Peter Rainer

Christian Science Monitor

"A brilliant throwback to the 19th-century battle between magic and science!”

David Edelstein

New York Magazine

“In Sherlock Holmes, we have the first Asperger’s detective.”

Manohla Dargis

The New York Times

But we really can’t play that game. Sherlock Holmes has been an icon for more than a century. You can’t just wipe that away. As much as they tried.

How much did they try? Ritchie, a Brit, is the first man to turn Sherlock Holmes into both an American and a Hollywood action hero.

The real Sherlock Holmes used his mind to solve crimes and mysteries. This one uses his mind, yes, but just as often, maybe more often, his fists. In the opening scene, as a female sacrifice writhes on a table (sexy!), Holmes and Watson take on a roomful of baddies as if they’re Jackie Chan and Jet Li.

The real Sherlock Holmes used the power of deductive reasoning to solve crimes, as does this one. But in the original stories, the evidence was there for us if we wanted to put it together ourselves. We rarely could. (Or I rarely could.) When Holmes did, however, we almost always went, “Of course!” Here, the evidence by which things are deduced is simply told to us after they’ve been deduced. Zip, zip, zip, zip. Get a move on. What’s that? You want to try to solve it? Just munch your popcorn, Einstein. Roller coaster’s pulling out of the station.

The real Sherlock Holmes was a cocaine user and violinist. He compared the brain to an attic—there’s only so much room, so you’d better be careful that what you put up there doesn’t crowd out worthier stuff. He had a smarter brother, Mycroft, and a nemesis, Prof. Moriarity, and a partner, Dr. Watson, who was sharp but not as sharp as Holmes, and he had informants, street kids, called the Baker Street Irregulars. He was a solitary man but found Watson’s help “invaluable”—which, to my 12-year-old ears, associating the prefix “in” with “the opposite of” (ex: “inconceivable”), sounded like the gravest insult when it was really his greatest compliment. He smoked a pipe. He wore a deerstalker cap.

This one? His plucks his violin, bowless, and smokes a pipe, ocassionally, and mentions Mycroft and sniffs some questionable substances. But cocaine and the attic aren’t mentioned, the deerstalker hat isn’t worn, and holy crap is he ever needy. The main personal tension within the film is his pain over Dr. Watson’s impending marriage to Mary (Kelly Reilly). He needs Watson with him whenever the game’s afoot. You get the feeling Irene Adler, Holmes’ love interest, shows up not only because it’s the movies and you need a girl but to quiet suspicions that Holmes might be gay.

My favorite bit was early on. Holmes is in a restaurant waiting for Watson and Mary. The other patrons talk, their cutlery clinks, and the noises intensify until it becomes almost unbearable for Holmes. It seems like Asperger’s. That would’ve been an interesting direction to go in. Of course it would’ve been less lucrative so they dropped it. Too bad. It would make sense of his seclusions. The world is too much with him. The acute senses that help him solve crimes also make it difficult to live in the world.

To the plot! Lord Blackwood (Mark Strong, who went on to play every villain in every movie made since) is the illegitimate son of Sir Thomas Rotheram (James Fox), head of a Freemasons-like secret society. Blackwood is responsible for the murder of several women—all writhing, one assumes—captured by Holmes, sentenced to death. But there’s something steely and menacing about him even behind bars or with the hangman’s noose around his neck. A week later, someone sees him rise from the dead. Then he’s killing again—not least his biological father.

Turns out he uses science and chemicals and whatnot (Holme’s wheelhouse) to appear magical and foster fear. He’s a 19th century terrorist. His goal is to take over Parliament and then—perhaps to ensure American audience interest—to reclaim Britain’s former colony across the pond. Amid a lot of running, fighting, explosions, and sniffing substances on his fingertips, Holmes stops him.

All the screenwriters mentioned above earned their pay; we get some fun stuff. There’s a giant Frenchman, Dredger (Robert Maillet), the “Jaws” of his day, whom Holmes must battle twice, and with whom he has the following exchange after Holmes’ weapon proves ineffective:

Dredger: Cours, lapin, cours. (Run, rabbit, run.)

Holmes: Avec plaisir.

Bailed from prison, where he has been regaling criminals with jokes and stories, Holmes has this exchange with the always incompetent Inspector Lestrade (Eddie Marsan):

Lestrade: You know, in another life you’d have made an excellent criminal.

Holmes: And you, sir, an excellent policeman.

I also like this exchange with Watson’s fiancee:

Mary: Making these grand assumptions out of tiny details.

Holmes: That’s not quite right, is it? In fact, it’s the little details that are most important.

The filmmakers do the “Batman Begins” thing of saving the iconic villain (Joker/Prof. Moriarity) for the sequel. All tentpole movies do this now. They’re all hoping for a “Dark Knight.” Good luck with that.

“Sherlock Holmes” is fun but it’s another part of our day-to-day disconnect. It’s a movie about a man of supreme concentration with which we distract ourselves for two hours. That’s the true game and boy is it ever afoot.

—December 15, 2011

© 2011 Erik Lundegaard