Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

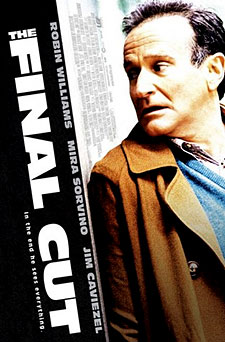

The Final Cut (2004)

At the end of the past century, Robin Williams became the King of Schmaltz. He bathed in it like it was cologne—“What Dreams May Come,” “Patch Adams,” “Bicentennial Man”—until audiences finally wrinkled their noses, fanned their faces and turned away. Robin! Please! Cut back a little, will ya?

He did. Completely. This century, with films like “One Hour Photo” and “Insomnia,” he’s transformed himself into the creepy, deadpan loner. No whiff of schmaltz anywhere. “The Final Cut,” by first-time writer-director Omar Naïm, continues this career trajectory. Unfortunately, it doesn’t mean we’re still not wrinkling our noses.

| Written by | Omar Naïm |

| Directed by | Omar Naïm |

| Starring | Robin Williams Mira Sorvino Jim Caviezel |

It’s the near future, and the big—seemingly only—technological change is that, before birth, a few people—one in 20, we’re told—have “Zoë chips” transplanted into their brains. These chips record their entire life. It’s a kind of immortality. Memories no longer disappear.

So how does this new technology transform society? Well, when somebody dies, a “cutter” is given their memories and splices them into a 100-minute “film,” to be shown at the deceased’s funeral.

And?

And that appears to be it.

Oh, we’re told that a rebellious 20-year-old, informed she has a Zoë chip, cleaned up her act (before committing suicide), but that’s the only example of people altering their behavior because they know their lives are being recorded. Otherwise it’s same old, same old. People bully, cheat, abuse. We’re still horrible.

It’s the cutter’s job, and Alan Hakman (Williams) is the proverbial “best in the business,” to delete any unpleasantness for the tribute film. Alan is a tight-faced workaholic, with the demeanor of a mortician, who sees himself as a “sin eater,” in part, because for 40 years a childhood sin has been gnawing away at him.

There is a growing movement against the Zoë implants, but the focus of the protest isn’t the invasion of privacy issue. (Imagine, for example, that your boss or wife or best friend was basically a camera, recording every interaction you had with them.) No, these punk Luddites with warlike, Native American tattoos, object on lifestyle grounds. “Remember for yourself!” they cry. (Surely the most flaccid slogan ever shouted.)

When Fletcher (Jim Caviezel), a former cutter, confronts Alan, his criticism is purely aesthetic. “You take people’s lives,” he complains, “and make lies out of them.” He’s accusing Alan, in other words, of creating schmaltz. He’s a film critic.

The plot: Alan’s latest assignment involves the disturbing memories of a Zoë Tech president, and Fletcher wants them for political reasons. Alan, in turn, winds up needing them for personal reasons.

None of it works. Tense moments don’t feel tense. The sociological implications of the chips are ignored for the personal trauma of Alan, which is dull and one-note. The lack of imagination, given the initial premise, is astounding.

—Origianlly appeared in The Seattle Times on October 15, 2004

© 2004 Erik Lundegaard