Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

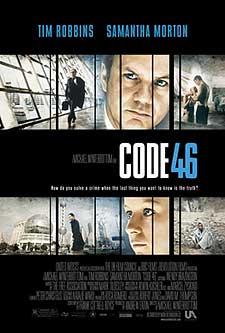

Code 46 (2004)

The near future tends to be a place where our fears of either too little or too much authority play themselves out. Too little authority leads to post-apocalyptic anarchy and bad clothes (“Mad Max”); too much authority—generally the chilling, technocratic kind—and individuality and love are squashed, although the clothes are better (“1984”; “Gattaca”). Michael Winterbottom’s “Code 46,” a film that was released last year in Britain, belongs to this second group.

Winterbottom’s near future is, at least, cleverly done-up. International travel is restricted to business-types who have insurance or “papelles”; the English language has become a polyglot of phrases (ni hao; dinero); and recreational viruses help people speak Mandarin or sing better.

| Written by | Frank Cottrell Boyce |

| Directed by | Michael Winterbottom |

| Starring | Tim Robbins Togo Igawa Samantha Morton |

More interestingly, Winterbottom and screenwriter Frank Cottrell Boyce (the duo who brought you “Welcome to Sarajevo” and “24 Hour Party People”) imagine laws that might be enacted if artificial forms of pregnancy—such as donor insemination, in-vitro fertilization and cloning—become widespread. Think about it. If you don’t know your parents, you may in fact be related to a host of strangers and possible sex partners. Since inbreeding is undesirable for society, how do you prevent such unsuspecting genetic incest? With Code 46, of course. Prospective parents, and unplanned pregnancies, are screened, and if the parents’ genetic identities match well, it’s just not allowed. All of this is told to the viewer at the beginning of the film.

Which is the film’s first mistake. OK, so that’s Code 46. And the movie stars Tim Robbins as an insurance investigator and Samantha Morton as a woman being investigated. What might happen? Exactly. We figure this out immediately, while it takes Robbins an hour. That’s a long time to be ahead of the curve.

The second mistake is Robbins himself. He plays William Geld, a buttoned-up corporate type (from Seattle, ironically, home of the unbuttoned corporate type), who uses an empathy virus in his insurance investigations to read people’s minds. Sent to Shanghai to investigate papelle theft, William quickly realizes Maria (Morton) is guilty but doesn’t finger her. Why? The oldest reason in the book: love.

So for the film to work, we have to believe that Robbins is a man who would risk career and family for love, and—to paraphrase Homey the Clown—Robbins don’t play that. His best roles, in “The Player” and “Bob Roberts,” are chilly corporate types. (Even in “The Shawshank Redemption,” he’s referred to as “a cold fish.”) No different here. Alternately cold and druggy, William leaves Maria’s bed not like a man tearing himself away from true love, but like someone regretting a one-night stand.

To be fair: William might not be a man in love. Winterbottom leaves that question open-ended—as he leaves so much open-ended.

“Code 46” is a moody, atmospheric film about a world sharply divided between haves and have-nots. It’s a distinct, fully realized and fascinating world; it’s the story Winterbottom places in the foreground that’s unfulfilling.

—Origianlly appeared in The Seattle Times on August 13, 2004

© 2004 Erik Lundegaard