Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

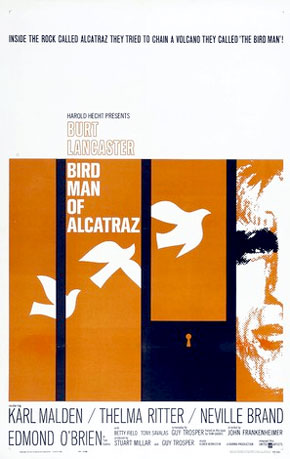

Birdman of Alcatraz (1962)

It's always interesting when actors, whom we've seen age in real life, play aged men in their younger days. The Hollywood version of getting old — a little gray on the temples, a moustache, some distinguished crow's feet — tends to be kinder than Time's version.

Written by:

Guy Trosper

Directed by:

John Frankenheimer

Starring:

Burt Lancaster

Karl Malden

Thelma Ritter

Betty Field

Telly Savalas

Academy Award Nominations:

Best Actor (Lancaster)

Best Supporting Actor (Savalas)

Best Supporting Actress (Ritter)

Best Cinematography

Quote:

“Any con steals canary eggs from another con is a dirty fink!”

The opposite holds true for Burt Lancaster in Birdman of Alcatraz. In his late 40s, he played a man who ages from 20 to 60 and they don't make him look good. His hair thins, he stoops, he shuffles. It's a very unegotistical performance. Compare this with the way Lancaster actually looked in his late 60s. He sprouted a neat salt-and-pepper moustache and distinguished crow's feet. He wound up looking like the Hollywood ideal.

Birdman of Alcatraz is the second of four collaborations between Lancaster and director John Frankenheimer, and much of the film is excellent. It starts in 1914. Robert Stroud (Lancaster), jailed for murder, is a surly, solitary man with a bizarre mother fixation. Cagney in White Heat comes to mind, but with Cagney you always got the feeling that as mean as he was, he still liked company. Not so Stroud. He is uncompromising in his isolation. Ah, but be careful what you wish for. After Stroud murders a guard he is sentenced to solitary confinement until the day of his hanging, which never comes about, because his execution is stayed by President Wilson. Foiled, the Attorney General decides to treat the initial ruling literally: To be kept in solitary confinement until hanged from the neck. Since no hanging, Stroud's in solitary for the rest of his life.

Solitary here isn't as bad as the solitary of most films. It's a room with a window, and there are guards to talk to if he wants, but mostly he doesn't. One guard, pitying him, asks if he'd like something to read. Stroud's hardass response, via Lancaster's quick, breathless delivery: "If I want something from you I'll ask for it."

The birds change him. Walking the yard during a thunderstorm he comes across a baby sparrow at his feet, takes it to his cell, and nurses it back to health. Turns out he's good with the bird, and other cons in solitary, charmed by the chirping, take up the practice. Trouble comes in the form of a rare disease that kills many of the birds, but it forces Stroud, with his third grade education, to read up on birds and diseases, and he becomes an expert in the field. This would stink of Hollywood storytelling if it weren't based on fact. Robert Stroud did exist, he did kill two men, and in solitary confinement he did become an expert on birds. His fame led him, briefly, out of solitary and into a laboratory, but the prison system fought back. In the middle of the night, he's moved — birdless — to Alcatraz.

The final third of the film is weak. Director John Frankenheimer came out of '50s television, with all of its stark, black-and-white morality plays, and the best of Frankenheimer on film (Manchurian Candidate, Seven Days in May) contains an aspect of this small-screen sermonizing. Birdman, too. The movie turns "social" on us. It's for certain things (prison rehabilitation) and against other things (rules, conformity). It all but forgets its title character in its desire to educate us.

The earlier character study was better. There's nothing quite so touching as seeing those tiny, fragile birds in Lancaster's large, benevolent hands.

—July 25, 1999

© 1999 Erik Lundegaard