Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

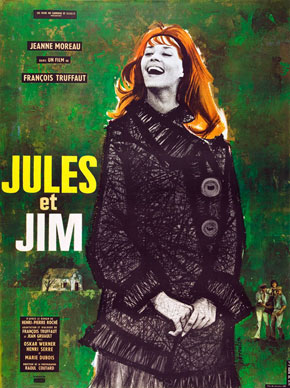

Jules et Jim (1961)

Jules et Jim is a romantic film about the horrors of love. It begins in Paris in 1912, with two friends, Jim (Henri Serre), a Parisian, and Jules (Oskar Werner), a visiting Austrian. Both are young, carefree Bohemians, and they spend their days French boxing, chasing women, and talking art and philosophy. The movie zips along with the exuberance of youth, the images and narration almost racing one another to see who can fit in the most stuff.

Written by:

Francois Truffaut

Jean Gruault

(based on the novel by Henri Pierre Roche

Directed by:

Francois Truffaut

Starring:

Jeanne Moreau

Oskar Werner

Henri Serre

Vanna Urbino

Anny Nelson

Boris Bassiak

Sabine Haudepin

Awards:

Best Non-American film at the Bodil Awards (Denmark), Jury Prize at the Mar de Plata Film Festival (Argentina), and Best Foreign Director from the Italian Syndicate of Film Journalists. Nominated for several British Academy Awards. Got nothing from Hollywood, and the Cesars didn't exist until 1976.

Quote:

"We played with life and lost."

Eventually Jules, a kind of sad sack, often wearing Buster Keatonish clothes, hooks up with Catherine (Jeanne Moreau), with whom he gets serious. Before he introduces Jim to her, he quietly beseeches, "Not this one, Jim." The three become friends, famously running across bridges and renting a house in the countryside. There's darker undertones, however. Catherine cannot abide being ignored, and after seeing a play and strolling around at 2 a.m., with Jules and Jim pontificating about the role of women in society and marriage, she suddenly throws herself off a bridge and into the Seine. They rescue her, of course, but afterwards one senses her boredom with Jules.

Then WWI intervenes and both Jules and Jim, on opposite sides, confess their fear of killing the other. After the war, Jim visits Jules and Catherine, now married and with a five-year old girl, Sabine, at their home along the Rhine. At first Jim thinks Catherine has settled down. "She's less of a grasshopper, more of an ant," he tells Jules, but Jules corrects him. Their marriage is a sham. She's cheated on him with at least three men, and they live in separate bedrooms. Jules seems defeated, impotent. His grand youthful artistic endeavors have narrowed into writing a book about dragonflies and joking about writing a love story on insects. "I am slowly renouncing her and all I had expected from the world," he tells Jim. This is only partly true. He's given up the hope of being Catherine's paramour but he can't give up her. He needs her physical presence like a drug. Fearful of losing her presence to his neighbor, he begins to nudge Jim in her direction. "Love her, marry her, and let me see her," he begs. The pace of the film here is leisurely, the exuberance of youth gone, and the circumstances — especially if the viewer has any sympathy for Jules — horrific. Slowly Jim and Catherine get together — in Jules' home. When Jim admires the nape of her neck and she offers it up to him, the camera pans outside where Jules is sawing a branch in half and we watch a piece of it fall off. There could not be a more apt metaphor.

Now it is Jim's turn to be in love. "Jim was a prisoner," the narrator tells us. "No other woman existed for him." Things begin to sour, though, when they are unable to produce a child, and Catherine impetuously returns to Jules' room, while Jim sensibly returns to Paris. If Jules represents absolute love, Jim represents a more relative version. His feelings for Catherine change according to her actions — although Jim, with his decades-long fiancee, Gilberte (Vanna Urbino), has his own problems as well.

Question: Is Catherine mad at the end? I would argue not. Plunging the car into the river — with Jim at her side — is a grander gesture than jumping off the bridge, but it's driven by the same impulse: the need to be center stage; the need to be absolute (the queen) in the eyes of her lovers. She cannot abide Jim's relative love and so she takes him down with her. If she was mad at the end, then she was mad at the beginning, too.

The film is based on an autobiographical novel by Henri-Pierre Roche, and, as a result, is often as loose and episodic as life, which leaves it open to many interpretations. Some see the film as feminist and the last line encourages this: "Catherine wanted [her ashes] to be cast to the wind, but that was not permitted." Others see it as misogynistic: the villainous female coming between two men and slowly draining the life out of them. Is it a celebration of the Bohemian or an acknowledgement that Bohemian lifestyles don't work? "New laws are beautiful," Jim says near the end of the film, "but it's more practical to obey the old ones. We played with life and lost." I have to admit that one of my interpretations was distinctly American. As Catherine impetuously moved from one bed to another, without care for the feelings of others, I kept thinking, "Somebody needs to get decked here."

All of these interpretations have validity but for me the key is in the line "We played with life and lost," which seems less an attack on Bohemian lifestyles (let's face it, their situation was hardly a traditional menage a trois) than a kind of hard wisdom that comes with the passage of time. Jules et Jim takes us from the exuberance of youth to the tranquility and impotence of middle age to the crunching of bones and ashes at our death — while a sad sack, Buster Keatonish figure walking away from the grave. Several of Truffaut's techniques, particularly the freeze frames, were subsequently overused in the '60s by other directors and thus feel dated; but all in all it was photographed beautifully and acted powerfully. It's a film to wonder over and debate about.

—February 5, 2002

© 2002 Erik Lundegaard