Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

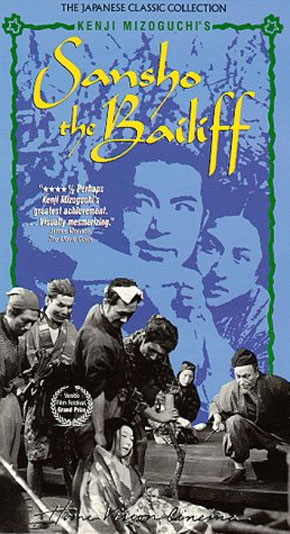

Sansho Dayu (1954)

Early in Sansho the Bailiff, which is filmed so beautifully and hauntingly that it feels like a ghost, Zushio, the 14-year-old son of an exiled governor in the late Heian period of Japan (794-1192), walks and plays through the forests, leading his mother, sister and servant as the four head to Tsukushi to join their father after many years apart. The father was exiled to Tsukushi because he refused a superior’s demands for greater taxes on the peasants, and for more peasants to fight his wars. The father was a benevolent governor, and as his son, Zushio, walks through the woods, he recalls his father’s wisdom: “Without mercy, man is like a beast. Even if you are hard on yourself, be merciful to others.” Some combination of the boy’s youth, solemnity, and the woods made me think: Mercy, by its nature, is a quality of the privileged — the powerless cannot grant it, only the powerful — and Zushio, a boy leading women through woods, is not powerful. He thinks he can grant what is no longer his to grant.

Indeed. The four, en route, are betrayed, separated and sold into slavery — the mother as a courtesan on the island of Sado, the children to Sansho the Bailiff, a domineering lord and the richest man in Tango. The world, a beast, is without mercy. Even the sympathetic son of Sansho, Taro, who cannot bear to brand with a hot iron the foreheads of runaway slaves, can do little to help the two children.

Ten years pass. Zushio grows to be not brutal but pragmatic. He forgets his father’s lessons — which caused the family nothing but harm — and is able, without much concern, to brand the runaway slaves for Sansho. His sister, Anju, is appalled by what he’s become. Without mercy he is a beast — in that he acts without thought. But a momentary reminder of happier times re-awakens him and he escapes to a temple, where he encounters Taro, now a monk, who shields him from slavehunters. Zushio plans to go to Kyoto to attempt to right the wrongs done to his family. Taro attempted the same on his behalf years earlier and warns him: “I found that humans have little sympathy for things that don’t directly concern them.”

At first Zushio’s supplicating petitition doesn’t go well — the chief advisor to the emperor doesn’t even listen to him — and he’s tossed in jail. A keepsake of his father’s, which he kept all those years as a slave, is taken from him, and here I thought, “The world will take everything, piece by piece, until he has nothing.” But the opposite occurs: The keepsake is recognized, and he is recognized as the son of a former governor and reinstated to his rightful position in the world. He becomes governor. Now the big question. Would he remember his father’s lessons? Or would he guard his position, knowing how tenuous it is, at all costs? Would he become merciful, pragmatic or cruel?

At one point Taro says to Zushio that “Unless [ruthless] hearts can be changed, the world you dream of cannot be true,” and an argument can be made that this film, by breaking our hearts, is an attempt to change our hearts. But it’s also more ambiguous. Early on, an uncle chastises the father for his benevolence, and the two have the following exchange:

Uncle: You’ve caused pain for your family.

Father: The peasants are in pain, too.

Uncle: Nonsense! You can’t compare us to peasants!

The father’s quality of mercy is profound, Christ-like, evolved, but, given what happens, you wonder how evolved a man can be in our world. How can anyone be for all mankind? Mustn’t your loyalties lie with a smaller group? Father and uncle, above, are simply arguing over the size of the group, and most of us, even in this more benevolent age, would side with the uncle. Hell, most of us are loyal to an even smaller group: a group of one.

The text at the beginning of the film tells us that this tale is from a time “when mankind had not yet awakened as human beings,” and we can argue forever on how, or if, we have awakened as human beings, but at least there’s this. The first words we hear are probably more relevant today. A mother’s voice to her child: “Zushio, be careful.”

—May 7, 2008

© 2008 Erik Lundegaard