Friday April 28, 2023

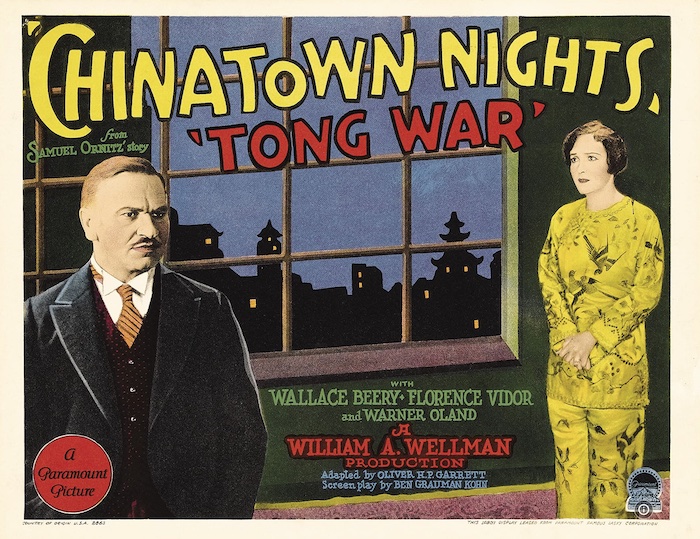

Movie Review: Chinatown Nights (1929)

WARNING: SPOILERS

It begins with one of those old-fashioned traffic signs—the word STOP comes up as the word GO retracts—and intentionally or not (not), it speaks to the movie’s troubled production. “Chinatown Nights” began as a silent film, but morphed into one of the first “all-talking” pictures, mostly through dubbing. And the dubbing is awful—out of synch and nonsensical. In these early traffic scenes, for example, we barely hear traffic. Instead we hear, very loudly, an unseen newsboy shouting “Extra, extra, read all about it!” And then suddenly we don’t hear him at all. We just hear a Chinatown tour bus guide’s schpiel about “sacred joss houses” and “ancient secret orders of the great Tong.” What happened to the newsboy? Where’s the traffic noise? It’s like an odd dreamworld. I felt a little nauseous trying to make sense of it.

Is this the movie that nearly ended Wallace Beery’s career? It was, at least, his first sound production, and sound is why Paramount dropped him. His voice was resonant, but, they felt, too deep and slow. So MGM’s Irving Thalberg picked him up and immediately made him one of the biggest stars of the early 1930s. (MGM also picked up the Marx Brothers after Paramount dropped them. Go know.)

Either way, “Chinatown Nights” did end Florence Vidor’s career, though not for any Lina Lamont reasons. Apparently she loathed what sound did to the moviemaking process, so she didn’t even bother to dub her own voice here; Nella Walker did that. And yes, she was Vidor as in King Vidor, her husband from 1914 to 1926. She did OK on the rebound, though, marrying famed violinist Jascha Heifetz in 1928.

Despite the movie’s troubles, it’s still kind of fascinating. I would love to see a crisp copy on a big screen rather than—as I did—a small muddy copy on my computer. It’s William Wellman, after all, making a gangster flick two years before “The Public Enemy.” How fun is that?

Dueling Shakespeare

Isn’t it also a kind of gender-reversed “Blue Angel”? The society dame brought low by the gangster. Though with a happy ending, if you can imagine.

Joan Fry (Vidor) is on a bad date with the drunk and handsy Gerald (Freeman Wood) when she becomes intrigued by the Chinatown tour bus. She also figures that, with Gerald, a public bus is safer than a private limo:

Gerald: You know, Chinatown is all a fake.

Joan: Then you should feel right at home.

The tour bus winds up running into a Chinese falldown artist. Except no, he’s actually dead, the victim of a brewing Tong War between Chuck Riley (Beery) and Boston Charley (pre-Charlie Chan Warner Oland, in yellowface). It’s Riley who shows up and orders the tour bus to scram, but Joan’s feisty so she sticks around. Then the cops show up and question her. Love that. There’s a dead body, there’s a known gangster, but wait, who’s this society dame? Maybe she had something to do with it!

After that, it’s late, there are no taxis, and men are being killed on the streets. Riley is the devil she knows. “Where are you taking me?” she asks, worried. “You’re following me,” he responds correctly.

After that, it’s late, there are no taxis, and men are being killed on the streets. Riley is the devil she knows. “Where are you taking me?” she asks, worried. “You’re following me,” he responds correctly.

Riley has a room above his nightclub with a giant war map along one wall, and a Chinese assistant, Woo Chung (Tetsu Komai), who doesn’t seem to do much. For her safety, Joan is locked in an adjacent room, from which she: 1) tries to escape; 2) emotes wide-eyed behind one of those speakeasy windows; 3) browses the bookshelf. There she finds a volume of Shakespeare with “C. Riley, Class of 1908” written on the title page. We get a nice scene of dueling quotes. She points out this one to Riley:

Upon what meat doth our Caesar feed

That he is grown so great?

He counters with “Richard III”:

Teach not they lips such scorn, for they were made

For kissing, lady, not for such contempt

Unlike the handsy Gerald, Riley doesn’t make a play, and in the morning she leaves reluctantly. Later, she returns to check out the Chinese Theater with society friends, who are already worried Joan might “go native.” Yes, they say that. It’s 1929.

By this point, a stuttering reporter, Williams (Jack Oakie), has instigated a meeting at the theater between the two Tong gangsters (cf., the scheming reporters in “The Racket”), Joan and her friends get in the way, men are killed. There’s a great shot of her caught in the mayhem afterwards—pushed along the crowd like someone caught in river rapids. So it’s Riley to the rescue again, even though he sees her as a slumming society dame, “down here looking us over like animals in a zoo.” Cake-eaters like her and her friends would faint if anyone slapped them in the jaw, he says, at which point she dares him to do it. So he does. Hard. And she? She holds her cheek and looks at him with something like love brimming in her eyes.

Yes, they do that. It’s 1929.

The Shadow

After they spend the night together, we get a particularly odd sequence that speaks to the jerryrigged nature of this production, the unknowability of relationships, or some really bad editing. Or all three.

Joan is about to leave for good but in the hallway heading downstairs there’s another society gal whom we’d seen earlier laughing at a Buddha statuette. Here, near the Buddha, she looks back at Joan and intones in a sing-songy voice, “Going … my way?” For some reason, that line causes Riley to burst out laughing, which causes Joan to spin and stare at him with hurt and tears in her eyes. Then the camera is on him. He seems upset that she’s crying. Or stunned? Maybe he’s stunned because in the next shot she’s closing the door from inside and letting her coat drop slinkily, sexily, to the floor. Except in the very next shot, from a completely different angle, with completely different lighting, she’s beatific, eyes cast up, as she intones in a sing-songy way, “I’ve changed my mind, Chuck. I’m going … your way.”

(For oddly slow, sing-songy voices, cf., Harlow in “Public Enemy.”)

But will she? She’s used to getting her own way, and now she’s just a moll. When he attends a potentially dangerous Tong funeral he refuses to bring her along. So she drinks. So she’s a drunk. (It happens that fast.) And when the cops show up to end the Tong war, and Riley refuses to help, she blurts out something he’d previously mentioned to her—that the cops just need to demand papers from all the Chinese and deport those who don’t have them, and that would end things. For that betrayal, Riley throws her out. But to where? “I can’t go back uptown now!” she cries.

As weird as Wellman’s sing-songy molls are, he’s really good with street kids: Darro and Coughlan in “Public Enemy”; the whole bunch in “Wild Boys of the Road”; and Jack McHugh here. He plays “The Shadow”—two years before the creation of the radio character—a street urchin who works for Riley and warns him when danger’s afoot. I kind of flashed on Brandon Cruz a bit. He’s not just loyal but cool. At one point, Riley throws a pot at him and he doesn’t flinch. He’s also empathetic. By now Joan is an alcoholic getting kicked out of Chinatown bars, so he takes her to his basement apartment and sleeps on the floor next to her.

The next day, he tries to get Riley to take her back, and that’s when Riley throws the pot. A second later, the kid is shot on the streets outside, the latest victim of the Tong war Riley won’t end. The kid’s dying words are addressed to him.

“Beat it, Chuck,” he says. “The cops are coming.”

The movie’s not much, but that scene is poignant.

So long Tong

The wrap-up is quick and odd. Boston Charley dumps Joan in front of Riley’s place—alive, with a taunting note about rotting fruit pinned to her—and a doctor, dressed like a milkman, tells Riley the only way she’ll survive is if he takes her away from all this. So he does. Like that. Snap. “We’re going … your way,” he intones. Then it’s back to the tour bus in Chinatown, which Boston Charley now rules, while new cake-eaters mock the proceedings.

And that’s it. No comeuppance for Riley. To be honest, it’s kind of refreshing.

Again, I’d like to see a good-quality version of this. Even better if someone removed the bad dubbing and restored the intertitles. How does it work as the silent film it was meant to be?

Early Hollywood really loved the Tong wars, didn’t they? They’re all over these plots but begin to die off in the 1930s. What happened? I guess the exotic storyline morphed into familiar heroes (Charlie Chan) and villains (Fu Manchu). Would be interesting if a modern filmmaker, Chinese or Chinese-American, took up the mantle. Particularly if we got something historically accurate. If that’s even possible.

Ever had the feeling you wanted to go, but also had the feeling you wanted to stay? Florence Vidor stayed in the movie, then left the movies.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)