Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

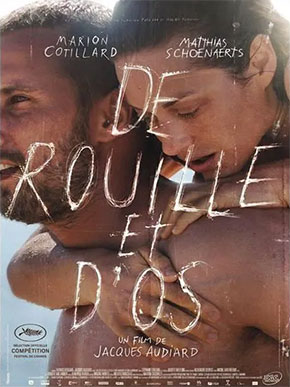

Rust and Bone (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I want the movies to stun me. I want to walk out of the theater in a daze. Hollywood didn’t help much in this regard this past year. They left it to the French to pick up the slack.

“De rouille et d’os” (“Rust and Bone”) is a beautiful film about tragic circumstances. In the hands of a lesser writer-director, it would be melodrama but Jacques Audiard (“Un Prophete”) makes poetry out of it. A bloody tooth, loosened during a fight, spins in slow motion on the pavement as if in dance. A woman whose legs have been cut off above the knee returns to the ocean, whose warm waters glisten. Later, with metal legs and cane, she walks down the steps at Marineland, where she once worked, and stands in silence before a large glass tank. She pats the glass once, twice. After a moment, a monster looms into view. An Orca. The Orca? The one who took her legs? One assumes not. One assumes that one has been killed but you never know and Audiard never says. We simply watch the whale move with her movements. It’s been trained, and she was one of its trainers. She’s confronting her past, finally, but it’s also a moment steeped in silence and mystery and beauty and forgiveness. It’s the best scene of 2012.

Being watched, getting bored

“Rust and Bone” is a tougher story to tell than Audiard’s previous film, “Un Prophete,” and not because Stéphanie (Marion Cotillard) loses her legs a half-hour in. “Un Prophete” was about one man: Malik. The camera follows him. Easy. This is about two people, Stéphanie and Ali (Matthias Schoenaerts), and for half the movie they’re not together. Audiard has to juggle their storylines. He has to bring them together, and apart, and together, in a way that feels real.

They don’t meet cute. He’s a down-on-his luck Belgian boxer with a five-year-old son, Sam (Armand Verdure), who comes to stay with his sister, a cashier, in a clapboard, motel-like apartment complex in Antibes, near Nice, on the southern coast of France. We watch him scrounge for food, steal, hitchhike. He’s not the best father. He often seems lost in thought but one can’t imagine the thought. He’s mostly just there.

Through a friend of his sister’s he gets a job as a bouncer at a club, L’Annex, and later that night there’s a fracas and Ali is restraining a guy who’s causing trouble. We see a woman’s legs, supine, on the dance floor, then her bloody nose. Did the dude punch her? Aren’t there laws against that? Not against punching women in general but Marion Cotillard. That’s like digging an elbow into the Mona Lisa or taking a hammer to Michelangelo’s David.

On the drive home, she’s drunk and distant, he’s matter-of-fact and clumsy. He mentions the way she dresses. How do I dress? she asks. He fumbles a bit. He doesn’t have the word. Actually he does, and uses it with a shrug: whore. She can’t quite believe him. This pattern will repeat itself.

It’s significant, of course, that we first see her as legs. It’s significant that he stares at her legs on the ride home. It’s significant that he goes up to her place to ice his knuckles, since his knuckles will have a rendezvous with ice later in the film.

After she’s lost her legs, and after they’ve begun what they’ve begun, we’ll get a better understanding of what might have happened that night at L’Annex. She makes this admission to him:

I liked being watched. I liked turning them on. I liked getting them all worked up. But then I'd just get bored.

Past tense. She obviously misses it—and doesn’t. She obviously doesn’t particularly like the person she was—but misses it.

We get a soupçon of her life before the Marineland accident, and at the hospital we see the result before she does. We see the absence and wait uncomfortably. This has been a famous scene before, notably in “King’s Row” with Ronald Reagan. “Where’s the rest of me?” he says. It’s probably the best acting he ever did. Cotillard blows him away. She grounds an unreal scene. Her trauma is overwhelming. “What did you do with my legs?” she says over and over, on the floor, crawling, because there are no other words. There are no other words for a long time.

Do you even realize?

Would Stéphanie and Ali have gotten together without the accident? There are barriers of class and attitude between them. He’s working class, she’s middle class or higher. She’s educated, he’s not.

But he’s exactly what she needs because he’s without pretense or pity. He does what he does, wants what he wants, shrugs away the rest. She’s been holed up in a state-run apartment for months when he first visits her. He wants to go outside; she doesn’t; they do. He wants to go swimming; she doesn’t; they do. “Do you even realize?” she says when he first suggests it. Do you even realize? He doesn’t. That’s his charm. On the boardwalk, she whistles for him, like a dog, and he carries her closer to the water, and then into the water, where she’s tentative at first—she doesn’t know how well she’ll swim without the bottom half of her legs. Then she feels it. Then she knows she can do it. In the audience I worried she’d try to swim away and drown herself but Ali has no such worry. He actually dozes on the beach, and she has to whistle for him again to come get her. “Fuck, this feels good,” she says.

It would be reductive to suggest she tames and trains this beast of a man, this mixed martial-arts fighter, the way she tamed and trained whales. He’s not much of a beast, for one. He has kindnesses. He’s just a lunk. He’s generally a considerate lunk but other times not. He’s impatient with his son, non-committal with his sister. He doesn’t think of the consequences of his actions. This helps with Stéphanie, initially, because others are walking on eggshells around her and it’s the eggshells that hurt. One day she talks about not having had sex since the accident, not knowing if it even works anymore, and as they’re doing dishes he brings it up:

He: You want to fuck?

She: What?

He: To see if it still…

She: Just like that?

Just like that. I like a scene, at the gym where we trains, where he watches a woman leading others in aerobics or yoga; then the two are outside smoking cigarettes and he says a word of greeting; then they’re fucking. Just like that. This tryst causes him to be late picking up Sam at school, for which he’s admonished by an administrator. Third time in two weeks, he’s told. Do you even realize? After a mixed martial-arts victory, he and his crew, including Stéphanie, go to L’Annex, but he leaves with another girl. She goes to the bar to drown whatever she’s feeling, and a clumsy, overbearing dude tries to pick her up. Then he sees her metal legs. Then he’s on eggshells. His apology implies this: I should have pitied you instead of lusted for you. He gets a drink in the face and a bloody nose. We’ve come full circle. The next morning she lays out the rules with Ali, who chafes under rules. But she’s matter-of-fact about it:

Let’s show some manners. I mean consideration. You’ve always been so considerate to me. We continue but not like animals.

One doesn’t expect much from his fight career but he’s good. He thrives on it. After one victory he’s so pumped he needs to expend more energy and bursts out of the van for a run. Some of the best moments in the movie are the small moments: the confused pride on Stéphanie’s face when she’s nonchalantly dismissed as “his girlfriend”; the way she jerks imperceptibly when he’s taken down; the look of amused pride on her face when she takes over as his manager and deals successful with the rabble of noisy, bartering men.

Of course, to me, any moment with Marion Cotillard’s face in it is a good moment.

Just like that

Things fall apart in a way that feels aesthetically pleasing. Ali helps his manager, Martial (Bouli Lanners), who is silent, bearded and gruff, install camera equipment at stores. Not to spy on customers but workers. It’s illegal, they’re found out, photos are taken by angry employees, and Martial has to leave town to avoid prosecution. But as a result of this work, Ali’s sister gets canned for taking expired foods that have been tossed by the company. Imagine: She takes in Ali, takes care of his son, and he gets her fired. Do you even realize? There’s a scene. There’s a shotgun. He leaves. Just like that.

Is the ending hurried? Suddenly Ali is training for national tournaments in the snow, and the sister’s boyfriend brings Sam to the camp for the day. They’re skating in their shoes on an iced-over lake, and Ali turns to take a piss. Behind him we see Sam disappear through the ice. Eventually Ali runs to the hole but finds his son some distance away, trapped beneath the ice. It’s a horrific image. He begins to pound on the ice with his bare fists. Something begins to crack but we don’t think it’s the ice. “Rust and Bone” is such a tactile movie. I doubt many people in the audience breathed during this scene.

In a voiceover we’re told about bones breaking and healing but how afterwards, as Hemingway said, some are stronger in the broken places. Not the bones in the hand, though. You feel those breaks the rest of your life. So I assumed his career was over. I assumed the movie was about a swimmer who loses her legs and a mixed martial-arts fighter who loses his fists, but in the final shots he’s with Stéphanie and Sam at a Warsaw hotel before a big, international match. So that’s not it. So I suppose it’s about the pain. It’s about continuing with a pain that won’t go away. I suppose that’s why we get, as the credits roll, Sigur Rós’ “The Wolves (Act I & 2)” sounding like a benediction:

Someday my pain

Someday my pain will mark you.

Harness your blame

Harness your blame and walk through.

I left the theater in a daze. I walked and walked and didn’t want to lose the feeling the movie gave me like a gift.

—February 3, 2013

© 2013 Erik Lundegaard