'Previously on The Hobbit...'

A friend of mine who usually writes of loftier matters has written a short review of “The Hobbit.” He's obviously a fan of Tolkien but not so much of Peter Jackson's new movie. Even so, this is the last line:

Let’s hope Jackson regains his footing in the next installment.

It made me think of this.

When we went to “Star Wars” in 1977, we went to see a movie. The movie began and it ended. It felt whole, and even gave us a symbol for wholeness: the Force.

When we went to “The Empire Strikes Back” in 1980, we were given a movie that was to be continued. I was actually shocked when I saw it in the theater. That's it? “To be continued” on TV meant next week; “to be continued” in a galaxy far, far away meant three years. Whenever anyone says “The Empire Strikes Back” was the best of the “Star Wars” movies, I generally respond, when I care enough to respond, “So how did you like the ending?”

When we went to see “The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring” in 2001, we knew we were going to see the first of a trilogy, based on a trilogy of books. That may be part of why it never interested me. I knew it would be continued. But at least it was based on a “To be continued” book.

“The Hobbit”? Based on a single book. But three movies. Because there's money in fragmentation.

We're not going to see movies anymore. We're going to see fragments of movies, fragments of narratives, that fit our fragmented times. Maybe we prefer it this way. Wholeness is so exhausting. Endings are so tyrannical. Fragments let us imagine any kind of escape from the narrative ... but hopefully an escape that leads us right back here, telling the same story, with a few variations. We want comfort and familiarity, with merely a chance of escape. We want to hear that story over again, Daddy.

Lancelot Links

- Favorite gay-themed movies? Awards Daily has the top 15 here. Not surprisingly, most are from the past 10 years. Elsewhere, in Hollywood Elsewhere, Jeff Wells objects to the exclusion of “Boys in the Band.”

- Steve Allen used to mock crappy rock 'n roll lyrics (or any rock 'n roll lyrics) by reading them aloud as if they were poetry. Maybe this is the updated version of that. That is, if you can mock anything in our “only thing worse than being talked about is not being talked about” culture.

- The New York Times' David Laskin spends “36 Hours in Seattle” and spends Friday night at some of my hangouts: Elliott Bay, Oddfellows, Sitka & Spruce. But no Molly Moon's? No Cafe Presse? And while he writes, vis a vis the Arboretum, “You don’t have to leave the city limits to immerse yourself in the region’s stunning natural beauty,” I'd still recommend it. If can choose when to come to Seattle, come in July and August and get out in the Cascades and Olympics.

- The New York Times editorial page takes down Gov. Paul LePage of Maine for the whole “mural in the Labor Dept. building” non-controversy. Takes him down, I should add, not gently.

- Not every governor is nuts. There's Gov. Mark Dayton of Minnesota, who, this week, became the first MN governor in decades to meet with citizens of North Minneapolis, and who stunned the crowd with a simple promise.

- From Vanity Fair, a pretty cool account, part of an upcoming bio on Robert Redford by Michael Feeney Callan, on the making of “All the President's Men.”

- Linton Weeks at NPR echoes my complaint: that we are not only a fragmented society but a fragment society; that we spend our cultural lives nibbling and sampling, not gorging. Options are too many, world is too confusing, attention spans are shot. And, yes, I didn't read the whole thing.

- ESPN's Jim Caple remembers Dave Niehaus.

- The guy whose house we were at to divvy up the M's tickets? Stephen Manes? He's quoted in today's New York Times about the new Paul Allen book, “Idea Man.” Why is he quoted? Because he wrote his own book, years ago, called “Gates: How Microsoft's Mogul Reinvented an Industry--and Made Himself the Richest Man in America”, so he knows a thing or two about the subject. His reaction to the revelation that Bill Gates tried to cheat Allen in the early days of Microsoft? Basically: “It's in my book.”

- The New Yorker's Ben McGrath has a nice piece on the Barry Bonds trial that calls into question: 1) its necessity; 2) the banning of PEDs from sports. I'm not buying it but it's definitely worth reading. Of course you have to buy The New Yorker (or borrow my copy) to do so. Only an abstract is available online. But as Rob Neyer wrote the other day, “It's the freaking New Yorker. If you enjoy the beauty of our language, you should be subscribing already.”

- Speaking of Neyer, he has a nice post, “Embracing the Beauty of the Unlikely,” on three of the Royals' Opening Day relief pitchers.

- I didn't know The Oatmeal dude lived in Seattle. But he does and he nails our less-than-fair city.

- The Woody Allen movie, “Midnight in Paris,” opening the Cannes Film Festival looks ... fun, actually. It begins like a continuation of some part of “Annie Hall”—she wants to hang, meet new people, etc., and he doesn't—but then something magic and funny seems to happen. At least one hopes. I haven't liked a Woodman film in more than a decade, so ... fingers crossed.

- Finally, the Minneapolis Star-Tribune's Colin Covert has a nice interview with the writer-director of the new comedy “Win Win,” the writer-director of indie hits “The Station Agent” and “The Visitor,” the co-screenwriter of the Pixar comedy, “Up,” and the actor who played scumbag preppy journalist Scott Templeton in the fifth season of HBO's “The Wire.” And it's all the same guy: Tom McCarthy.

When journalists were the heroes.

Which Host with What Most?

I agree with the Hollywood talent agent in this Patrick Goldstein post: Having Ricky Gervais host the Golden Globes is the Globes' gain and the Academy's loss. He's one of the funniest men on the planet, and, being British, he's at least somewhat international, although I doubt his shows carry far into Europe, let alone Asia or Latin America. His movies certainly don't.

So what's the Academy looking for in a host? What's their goal—to increase U.S. ratings or international ratings? “Both,” I'm sure someone would say. But if they had to choose, wouldn't they want the latter rather than the former? And what are the international ratings of the Academy Awards? I remember how common it once was to talk about “a billion people watching” but they haven't trotted that one out in a while, and a quick Google search gives us, at best, vague reports, like this one from Variety: “Some suggest that as many as 800 million people watch the Oscarcast worldwide.” I like that. Some don't even “say” it; some merely “suggest” it. Some gossip that... Some spread rumors that... It's called news.

The U.S. numbers, meanwhile, are no mere suggestions, and they are definitely dropping. No year in the '90s dipped below 40 million—with the high point being the 57 million who watched “Titanic” win—while no year in the last five years has risen above 40 million. These ratings drops correlate with the drop in the box-office numbers of the best-picture candidates, so one wonders how much a host can counter this trend. Isn't that what the idiotic expansion of the best-picture candidates is for?

Even so, who would you pick as your Oscar host? Another funny TV star—like Johnny Carson, David Letterman or Jon Stewart? Another funny movie star—like Bob Hope, Billy Crystal or Steve Martin? A song-and-dance man like Hugh Jackman? Apparently the show's new producers, Bill Mechanic and Adam Shankman, are seeking co-hosts, rather than one host, to appeal to the different demographics in our increasingly fragmented country in our increasingly international world. So who could that be? Brad and Angelina? Tom Hanks and Julia Roberts? Justin Timberlake and Beyonce? Who matters in the movie world anymore?

This last question actually clarifies. If movie stars no longer matter, as the box-office numbers indicate, you go with what does. Thus: Welcome! To the 82nd Annual Academy Awards! With presenters: Harry Potter! The Dark Knight! Optimus Prime! Captain Jack! Spider-Man! Iron Man! And Darth Vader! And now, here's your hosts, Shrek and Donkey!

Here Come the Critics

“Critics” hardly seems the right word, does it, when they‘re listing off the best of the year. “Here Come the Praisers.” “Here Come the Complimenters.” More basically: “Here Come the Analyzers.” They’ve sifted through the year in movies, analyzed what's good and bad, and left us what's good. How nice! They‘re like Santa Claus. An underappreciated Santa Claus.

This is what the tally looks like thus far:

| Critics Group | Best Picture | Best Actor | Best Actress | Best Director | Best Foreign Language Film |

| NY Film Critics Circle (1935) | “The Hurt Locker” | George Clooney, “Up in the Air” | Meryl Streep, “Julie & Julia” | Kathryn Bigelow, “The Hurt Locker” | “L’Heure d‘ete” |

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association (1975) | “The Hurt Locker” | Jeff Bridges, “Crazy Heart” | Yolanda Moreau, “Seraphine” | Kathryn Bigelow, “The Hurt Locker” | “L’Heure d‘ete” |

| The Boston Society of Film Critics (1981) | “The Hurt Locker” | Jeremy Renner, “The Hurt Locker” | Meryl Streep, “Julie & Julia” | Kathryn Bigelow, “The Hurt Locker” | “L’Heure d‘ete” |

| Washington DC Area Film Critics (2002) | “Up in the Air” | George Clooney, “Up in the Air” | Carey Mulligan, “An Education” | Kathryn Bigelow, “The Hurt Locker” |

“Sin Nombre” |

A sweep thus far for Bigelow, and consensus for “The Hurt Locker” and “L’Heure d‘ete” (“Summer Hours”), the latter of which I’m particularly happy about since I thought that movie was flying under the radar. I was lucky enough to see it at the Seattle International Film Festival in May or June and recommend it to anyone and everyone—when it finally comes out on DVD. It's a movie that works on you in subtle ways and stays with you in profound ways.

Most observers list off these types of awards as precursors to the Oscars (what does it mean, who's agreed with the Academy in the past, blah blah blah), but for once I thought it would be nice to just enjoy the movies mentioned, and the critics groups mentioned, on their own. I haven't seen “Sin Nombre” and “Crazy Heart” but everything else is worth seeing. These are all movies, stories, that, while trying to entertain, make us feel what it means to be alive: as an IED specialist in Iraq in 2004; as a working-class girl in England in the 1960s; as a working-class artist in turn-of-the-last-century France; and as a French family in an increasingly international and fragmented world. Also what it means when we go.

Lancelot Links

- From Neal Gabler: Finally! Someone else comes out against the Academy's switch from five to 10 nominees for best picture. Then he goes too far. He blames a general cultural inflation within democracy—everyone demanding, and getting, what they want, so everyone feels good about themselves—but, to me, a greater source of the movie industry's problem (and thus the Academy's problem) is the fact that studios target specific demographics within our increasingly fragmented society. “We‘ll make this for 13-year-old boys, this for 13-year-old girls, this for fans of horror, and this for awards shows. And this last movie we’ll release in New York and L.A., then in select cities, and maybe one day we‘ll widen it to a quarter of the theaters that, say, a cartoon about gun-wielding hedgehogs played in. When it doesn’t do well, we‘ll scratch our heads and say, ’Well, I guess the audience for serious drama isn't what it used to be,' and we‘ll stop making those kinds of films.” Of course it could be that the audience for quality drama isn’t there anymore. Or it could be that this audience has simply shifted indoors, waiting for DVD or PPV. But I'd guess very few players in Hollywood are trying to make movies for a general audience anymore.

From Uncle Vinny: Simon Heffer's piece in the Telegraph (UK) is as much a slam on the moribund British film industry as it is a paean to modern French cinema, and, at least to this latter issue, I agree, agree, agree. Obviously he loses me with this statement—“Almost every Hollywood film is now made to appeal to such a broad audience...”—since, as I argue above, Hollywood isn't trying to appeal broadly but specifically: to 14-year-old boys. (The result is the same: stupid films.) I was also saddened to read Mr. Heffer's appreciation of “Mesrine,” starring Vincent Cassel. Not because I disagree but because I haven't been able to see it yet. I had tickets for both parts at last year's Seattle International Film Festival (SIFF) but it was pulled at the last instant. Forget why. According to IMDb.com, it doesn't even have a U.S. distributor. DVD? Not in this country. It sits in my Netflix “saved” queue, along with a dozen other great or interesting films, such as “OSS 117: Lost in Rio” and “The Century of the Self.” And don't even get me started on where the hell “Bienvenue chez les Ch‘tis” is. But thanks to Mr. Heffer I have added “Le gout des autres” to my queue. The most startling thing about his article, though, is that he spends a thousand words praising modern French film and doesn’t mention “L‘heure d’ete.”

From Uncle Vinny: Simon Heffer's piece in the Telegraph (UK) is as much a slam on the moribund British film industry as it is a paean to modern French cinema, and, at least to this latter issue, I agree, agree, agree. Obviously he loses me with this statement—“Almost every Hollywood film is now made to appeal to such a broad audience...”—since, as I argue above, Hollywood isn't trying to appeal broadly but specifically: to 14-year-old boys. (The result is the same: stupid films.) I was also saddened to read Mr. Heffer's appreciation of “Mesrine,” starring Vincent Cassel. Not because I disagree but because I haven't been able to see it yet. I had tickets for both parts at last year's Seattle International Film Festival (SIFF) but it was pulled at the last instant. Forget why. According to IMDb.com, it doesn't even have a U.S. distributor. DVD? Not in this country. It sits in my Netflix “saved” queue, along with a dozen other great or interesting films, such as “OSS 117: Lost in Rio” and “The Century of the Self.” And don't even get me started on where the hell “Bienvenue chez les Ch‘tis” is. But thanks to Mr. Heffer I have added “Le gout des autres” to my queue. The most startling thing about his article, though, is that he spends a thousand words praising modern French film and doesn’t mention “L‘heure d’ete.”- From David Carr: One of the best journalists working smartly reminds us that it's not Leno, Conan nor Zucker who's responsible for this debacle; it's you and me. The audience for traditional late-night shows is being lost to other media, primarily this one, and if Leno's ratings are slightly higher than Conan's it's because his audience is older and less likely to be here. Moving Jay back to the “The Tonight Show” is like moving a man to the driest part of a sinking ship—and knocking over other passengers, including a tall redhead, in order to do it. That man might last a little longer but it's hardly stopping the ship from sinking.

Who's Controlling the News? Not Auletta

“You missed it.”

I kept thinking of that line from “All the President’s Men” while reading Ken Auletta’s Jan. 25th New Yorker piece, “Non-Stop News: Who’s Controlling White House Coverage?” Auletta missed the story. Shame. I normally like Auletta.

The story for me doesn’t begin until the fifth of 11 sections, the one beginning “Like other American workers, journalists these days are crunched, working harder with less support and holding tight to their jobs” and ending with a quote from Chuck Todd, who, this section tells us, is not only NBC’s White House correspondent and political director, but is busy from dusk 'til dawn with appearances on “Today,” “Morning Joe,” his own (aptly named) “The Daily Rundown,” along with the usual blogging and tweeting from and to various sites. The news cycle is now a cycle in the way that time is a cycle. It never stops. As a result, Todd, and other journalists, have no time for in-depth coverage or even deep thought or analysis. “We’re all wire-service reporters now,” Todd says.

The sixth section is also about how technology has transformed media matters but this time from a White House perspective. “The biggest White House press frustration is that nothing can drive a news cycle anymore,” Republican political advisor Mark McKinnon says. Auletta then goes on to criticize the Obama White House for being too slow and reactive. He criticizes Press Secretary Robert Gibbs because “he rarely asserts control from the podium, to steer the press onto the news that Obama wants to make.” I.e., He’s not telling the newsmen what the news is. One could argue he’s treating them like adults.

So if we’re all wire-service reporters now, and the Obama White House isn’t steering these reporters towards the news, who is? That’s where it gets scary. Auletta writes: “What the press is paying attention to, [former Obama White House Communications Director] Anita Dunn says, is cable and blog attacks on the Obama Administration.” And who’s steering those? Guess.

That’s the story: In an increasingly fragmented, perpetual news-cycle world, who or what is steering the news? That’s even the story in Auletta’s headline, isn’t it? And he still misses the story.

Because much of Auletta’s piece is old news. Has the mainstream media been pro-Obama? Is Pres. Obama too prickly with the media now that the honeymoon is over? Should he be lecturing the media on its faults the way he does? About how the media focuses on the most extreme elements on both sides? About how they’re only interested in conflict?

Early on, Auletta quotes from a PEW Research Report on Obama’s early glowing press coverage:

The Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism, a nonpartisan media-research group concurred; tracking campaign coverage, it found that McCain was the subject of negative stories twice as frequently as Obama. (The study says that the press was influenced by Obama’s commanding lead in the polls—the kind of ‘Who won today?’ journalism he now decries.)

Allow me a sports metaphor. Do we assume that Albert Pujols gets more positive press coverage than, say, Yuniesky Betancourt? Of course he does. He’s a better ballplayer. Our eyes see it, the stats prove it. Unfortunately, politics has no such stats beyond poll numbers and votes. I’m not suggesting that Barack Obama is Albert Pujols; I’m merely suggesting that, in dealing with two political figures, we’re not dealing with two interchangeable blocks of wood. I’m suggesting that the mainstream press cannot pretend that the Yuniesky Betancourts of the political, legal or business realms are equal to the Albert Pujolses of same, without losing as much credibility as they would if they misreported facts. Objectivity is not stupidity. Let me add, not being a journalist, that I have no idea how you work this out within the constraints of objective journalism. But make no mistake: This is an issue for objective journalism. If objective journalism is to survive.

Perhaps more importantly, does the Pew Research Center Project include FOX News and conservative radio in their study of mainstream media? If not, why not? The notion that “the media” is limited to The New York Times goes against what should be the brunt of this article. We’re in the middle of a whole new ballgame.

Auletta quotes ABC’s Jake Tapper on the matter. “This President has been forced to deal with more downright falsehoods than any President I can think of,” Tapper says. Auletta then lists off some examples: “Obama was brought up a Muslim; he was not born in the U.S.; he studied at a madrassa in Indonesia.” How about: Obama is Hitler? He wants to kill your grandmother? He’s destroying the foundation of American society? That’s daily fodder in these venues, and it keeps seeping out, and it becomes the story. Even when it becomes the joke story, on “The Daily Show,” or “The Colbert Report,” it’s still the story. In addressing these falsehoods in an objective matter, or a jokey matter, how are you not perpetuating these falsehoods? That’s the issue. This was the issue in the summer of 2008 and in the fall of 2009. And today. And for 10 pages of prime New Yorker real estate, Auletta misses it.

The Bad Box Office of the Best Picture Nominees

There are a lot of stories making the rounds about this year's Oscar nominations. Both “American Sniper” and “Mr. Turner” did surprisingly well while “Selma” was all but denied. As was “The LEGO Movie.” As was “Life Itself,” the documentary about the life and death of film critic Roger Ebert. But then its director Steve James also directed the hugely acclaimed “Hoop Dreams,” which went unnominated in the documentary category in 1994. So ... fool me twice, I guess.

But for me, the big story is still the box office. Its lack.

Here are your eight best picture candidates, their domestic box office totals, and their widest distributions:

| Movie | Box Office | Theaters |

| The Grand Budapest Hotel | $59.1 | 1,467 |

| The Imitation Game | $42.0 | 1,566 |

| Birdman | $26.5 | 862 |

| The Theory of Everything | $26.0 | 1,220 |

| Boyhood | $24.3 | 775 |

| Selma | $15.5 | 2,179 |

| Whiplash | $6.1 | 419 |

| American Sniper | $3.3 | 4 |

Reminder: in 2009 the Academy broke a 60-plus-year tradition and expanded its best picture candidates from five to 10 mostly because popular movies weren't getting nominated and people were turning away from the Oscar broadcast. The Academy didn't want to become marginalized. Thus: 10 nominees. Then five to 10.

And it seemed to work.

In 2009, the Academy nominated five pictures that grossed more than $100 million domestic, including Nos. 1, 5 and 8 on the year (“Avatar,” “Up” and “The Blind Side”). In 2010, five more with more than $100 mil, including Nos. 1 and 6 on the year (“Toy Story 3” and “Inception”). 2011 was a step back: just one with > $100 mil domestic, “The Help,” which was the 13th most popular movie of the year. In 2012, six movies breached $100 million, but none higher than 13th: Spielberg's “Lincoln.” Last year? Four, including the sixth-highest-grossing film, “Gravity.”

And this year? The highest-grossing film topped out at $59 million and 53rd place for the year.

It's actually worse in the acting categories. The highest-grossing film in Best Actor is “Imitation Game” at $42 million; in Best Supporting Actor, it's “The Judge” at $47. Rosamund Pike's “Gone Girl” ($167) and Meryl Streep's “In the Woods” ($106 and climbing) at least get us over the $100 million mark, but they're the only two among the 20 acting candidates. Everythign else is below $50 million.

This will change, obviously, but by how much? “Into the Woods” will do better but not because of Oscar. I could see “Imitation Game” gaining some moviegoers. Will they expand “Birdman”? Will they re-release “Whiplash”? Are people psyched to see “American Sniper” now? Will its distributor let folks outside NYC and LA see it?

It's a bit worrisome. In 2009, when the Academy expanded its best picture category, I created the following to chart to indicate why it had done so:

The Annual Box Office Rankings for Best Picture Nominees, 1991-2008*

| Year |

BPN BO rank |

BPN BO rank |

BPN BO rank |

BPN BO rank |

BPN BO rank |

| 2008 | 16 | 20 | 82 | 89 | 120 |

| 2007 | 15 | 36 | 50 | 55 | 66 |

| 2006 | 15 | 51 | 57 | 92 | 138 |

| 2005 | 22 | 49 | 62 | 88 | 95 |

| 2004 | 22 | 24 | 37 | 40 | 61 |

| 2003 | 1 | 17 | 31 | 33 | 67 |

| 2002 | 2 | 10 | 35 | 56 | 80 |

| 2001 | 2 | 11 | 43 | 59 | 68 |

| 2000 | 4 | 12 | 13 | 15 | 32 |

| 1999 | 2 | 12 | 13 | 41 | 69 |

| 1998 | 1 | 18 | 35 | 59 | 65 |

| 1997 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 24 | 44 |

| 1996 | 4 | 19 | 41 | 67 | 108 |

| 1995 | 3 | 18 | 28 | 39 | 77 |

| 1994 | 1 | 10 | 21 | 51 | 56 |

| 1993 | 3 | 9 | 38 | 61 | 66 |

| 1992 | 5 | 11 | 19 | 20 | 48 |

| 1991 | 3 | 4 | 16 | 17 | 25 |

* Best picture winner represented in red.

Then for comparison's sake, I added this one.

| Year |

BPN BO rank |

BPN BO rank |

BPN BO rank |

BPN BO rank |

BPN BO rank |

| 1970 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 11 |

Here's this year's nominees:

| Year |

BO rank |

BO rank |

BO rank |

BO rank |

BO rank |

BO rank |

BO rank |

BO rank |

| 2014 | 53 | 76 | 94 | 96 | 100 | 115 | 138 | 158 |

Yes, I'm concerned that the stories we share these days tend to be cartoonish; that there are fewer and fewer serious stories that we all know and care about. I think this is helping an increasingly fragmented and polarized society become more so.

But mostly I'm worried about what the Academy might do to rectify the situation. Particularly if the ratings tank on Feb. 22.

Among the nominees, Wes Anderson was most popular at the box office. It's a position he's never been in before.

Review: “Tyson” (2009)

WARNING: HEAVYWEIGHT SPOILERS

The most surprising admission in “Tyson,” James Toback’s documentary about former heavyweight champion Mike Tyson, isn’t that Tyson was scared heading into the ring, nor that he wanted women to protect him—him, the baddest man on the planet. It’s this: When he was young, Mike Tyson was Woody Allen.

The revelation comes early in the doc, which consists almost exclusively of old fight footage and present-day Tyson interviews. Tyson, bald now, Maori warrior tattoo sweeping one side of his face, and dressed in a pressed, button-down shirt and slacks in a Hollywood mansion, tries to explain who he is by explaning where he came from: the Brownesville section of Brooklyn, where, he says, it was “kill or be killed.” He talks about getting picked on. He talks about getting money stolen from him—quarters and change—by neighborhood gangs. Then he talks about how someone once took his glasses and broke them. The image that comes to mind is Virgil Starkwell forever having his glasses stomped on by bullies in “Take the Money and Run.” Mike Tyson was Woody Allen? Who knew?

A second later you narrow your eyes. Wait a minute. Glasses? Did Tyson need them as a kid? Did he stop needing them as an adult? You believe Tyson when he says, of the man who lived with his mother: “He might have been my father... I believe he was my father... I was told he was my father”— a sequence that Toback splices together to great echoing effect. But the glasses thing?

Or was he talking about sunglasses?

That’s part of the challenge of “Tyson.” How much do you buy into what he’s saying? When is he bullshitting us? When is he bullshitting himself? And when is James Toback putting too personal a stamp on Tyson’s story? Half the film is rise and half is sad fall, and Toback ends the first part with Tyson saying, “Once I’m in the ring, I’m a god. No one can beat me.” Then we get a slow fade and a slow open on Robin Givens. The implication is that everything began to go wrong with her, but, truly everything began to go wrong with the “god” comment and the hubris it represents. Pride, as always, goeth.

That’s part of the challenge of “Tyson.” How much do you buy into what he’s saying? When is he bullshitting us? When is he bullshitting himself? And when is James Toback putting too personal a stamp on Tyson’s story? Half the film is rise and half is sad fall, and Toback ends the first part with Tyson saying, “Once I’m in the ring, I’m a god. No one can beat me.” Then we get a slow fade and a slow open on Robin Givens. The implication is that everything began to go wrong with her, but, truly everything began to go wrong with the “god” comment and the hubris it represents. Pride, as always, goeth.

Tyson was trained by Cus D’Amato—who deserves his own doc, and who died in November 1985, a year before Tyson knocked out Trevor Berbick in the second round to become heavyweight champion of the world. Then he was trained by Kevin Rooney, but Tyson fired him in late 1988. He was managed by Jim Jacobs and Bill Cayton. But Jacobs died in March 1988 and Don King suddenly insinuated himself into the picture, fighting and apparently beating Cayton over Tyson’s contract. Why did Tyson go along with this? What part did racial politics play? And why doesn’t the doc focus on it more? Toback blames the lack of training, the partying, the women, but all of this is related to a larger issue: Tyson stopped dancing with those who brung him.

Tyson is surprisingly kind to Givens. He calls her “this young lady.” He says “everyone was in our business.” He says “We were just kids, just kids, just kids.” He doesn’t know why she lied to Barbara Walters on national television—Givens, with Tyson hanging over her shoulder, tells Barbara, and the country, that Mike, the heavyweight champion of the world, is a manic depressive, that their marriage has been pure hell, that “it’s been worse than anyone could imagine”—but in this doc he more or less gives her a bye.

Not so with others. “When I was falsely accused of raping that wretched swine of a woman, Desiree Washington, it was the most horrible moment in my life,” he says. He calls Don King “just a slimy, reptilian motherfucker” who would “kills his own mother for a dollar.”

He’s also hard on himself. He owns up to a lot. That he likes strong women whom he can sexually dominate. That when Cus D’Amato first takes him to his mansion, he’s thinking of robbing him: “I could rob this white guy,” he thinks.

He breaks down on camera talking about Cus. It seems the most important relationship in his life. At the same time he says, “I was like his dog. He broke me down. He broke me down and rebuilt me.” Cus also gave him speed, power, confidence. The doc is separated between those who built up Tyson’s confidence (D’Amato, mostly) and those who tore it down (Givens, Washington, King).

Remember how fierce he was? He had 15 fights in 1985 and won all of them by KO or TKO, 11 of them in the first round. He was built like a bullet and seemed just as unstoppable. He was so tough he inspired the toady in other men. Hell, I even felt it from afar, joking about his prowess in the ring, luxuriating in his power as if it were in any way related to my own (lack thereof). Or maybe I simply liked how much of a unifying concept he was in an increasingly fragmented world. He unified all the heavyweight belts that had been scattered to the four winds. For years no one argued over who the best boxer was. The only question was the question the announcer asked after Tyson destroyed Michael Spinks at 1:31 in the first round in a heavyweight bout in 1988: “Who in this world has any chance against this man?”

Himself. He was not a god. Gods don’t have to train, but he did, and he lost to Buster Douglas in 1990 in one of the greatest upsets in boxing history. We kept waiting for him to unify things again but he kept stumbling. First the rape charge, then the conviction. He lost three years. When he came out of prison, he was a Muslim. This too seemed sad, like it was part of someone else’s story, as it was. It was Malcolm’s and Muhammed Ali’s. Tyson was clinging to cliches.

I’d forgotten that he won the heavyweight championship again in the mid-1990s. I didn’t know, in the infamous ear-biting match with Evander Holyfied, that Tyson claimed Holyfield headbutted him first. I’m not a boxing fan so I didn’t know. But I knew so much else because Tyson seeped through to the general culture in a way no boxer has since. Who’s even the heavyweight champ now? I had to look it up. A Russian and two Ukranian brothers. Three Great White Hopes. Scattered to the four winds.

“Tyson” is an untraditional doc in that there are no other talking heads. Would it have been better with other voices? Maybe. Would it have been better without Tyson walking along a Malibu beach? Yes. That Hollywood home, it turns out, was rented by Toback. So where does Tyson live? Why didn’t they film there? Why this fake Hollywood backdrop?

It’s still effective. The former champ seems lost in the way of former champs. “Old too soon, smart too late,” he says. “”What I’ve done in the past is a history, what I’ll do in the future is a mystery,” he says. The final shot is a freezeframe on his battered, confused face. He once thought himself a god. Now he’s just another man who can’t make sense of his life.

Lancelot Links (Wants to Deck Someone)

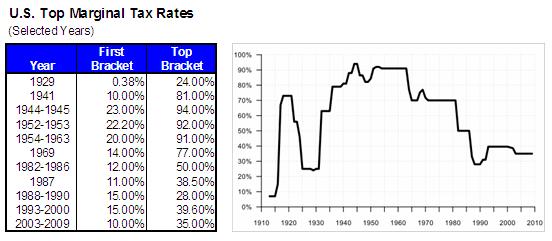

- John Perr's blog, "Crooks and Liars," takes Sarah Palin apart for her massive ignorance of the history of our country, but equally important, not to mention related, is the accompanying graph (below) on the recent tax rate of our lowest and highest income brackets. During World War II, which Palin insists, in a Washington Post Op-Ed of all places, was paid for by war bonds (volunteerism), the top income bracket was taxed at 94%. Ninety-four percent! So much for voluteerism. Now they're taxed at 35 percent. Me, I'd raise it back to at least 50 percent —at least—as it was from 1982 to 1986. Reagan years, people. Everyone in this bracket is making tons of money off of a system they were born into and it's time they showed their appreciation to that system, and the long-term stability of that system, by, yes, "volunteering" to give back. Read the whole piece, it's worth it:

- My man! Sen. Al Franken (D-MN) takes down Sen. John Thune (R-SD) on the health care bill. Franken, by way of Pat Moynihan, has given us a mantra for this age of disinformation: "You're entitled to your own opinion, you're not entitled to your own facts." I particularly like how frustrated and angry Franken gets by the end. You can tell he's fed up. These people keep lying.

- It's actually worse. These people make careers out of accusing the opposition of doing what they do. It's the absolutist right, not the relativist left, that's as close to a fascistic organization as this country has ever had. The Nazis, remember, started out as a vocal minority, an absolutist, bullying, hateful group that wheedled its way into power and then shut out all opposition. That's the absolutist right in this country. And their latest alley-oop accusation? Via the Daily Show: Global-warming debunkers are now accusing global-warming proponents (i.e., the scientific community) of believing what they believe...for money! The idea being that global warming is big business so it doesn't matter if it's true or not. Nice. Because we all know it's the opposite of that. Global warming continues because of big business, because of the money that's made pumping what we pump into the air. The whole thing is so awful it makes you want to retch. It makes you want to deck somebody.

- A voice of reason in this wretched political world? Hendrik Hertzberg. Again.

- And another. It's worth watching Pres. Obama interviewed by Steve Kroft on "60 Minutes." He's a serious man in serious times surrounded by the unserious and the moronic. By people who are dicking around. And not just the absolutist right and not just the mainstream media but you and me. We create all of this. Every second, with every decision, we create our world.

- And even this serious interview gets an idiotic response from Dana Perino, whose 15 minutes, in a normal world, that is a non-cable, non-fragmented world, would be up. Yet she keeps talking. She says that President Obama's suggestion that President Bush "was too triumphant in his rhetoric when talking about war...is demonstrably false." The obvious follow-up? "Can you demonstrate it?" But she was on FOX News so they didn't ask the obvious follow-up. Here. Here are the three words that demonstrate the truth of what Pres. Obama implied about Pres. Bush: "Bring 'em on." Do we need more? Do we need to recall the swagger and the smirk? The aircraft carrier and flight suit? The "Mission Accomplished" banners? The talk of good and evil? The covering up of America's war dead? Damn, people, it wasn't even 10 years ago.

- But apparently some people can't even remember January 19, 2009.

- First, The Daily Show helped expose Glenn Beck's inciting panic/encouraging gold-buying and repping for Goldline. Now it's The Colbert Report's turn. "'Pray on it.' Like we're preying on you." Brilliant. Here's an in-depth look from the L.A. Times. The question that needs to be asked—and I mean this—is: Why is Glenn Beck trying to destroy this country?

- To end on an up note, here's Pres. Obama's speech after winning the Nobel Prize. It's a serious speech by a serious man in serious times. Read the whole thing. An excerpt:

- We must begin by acknowledging the hard truth: We will not eradicate violent conflict in our lifetimes. There will be times when nations -- acting individually or in concert -- will find the use of force not only necessary but morally justified.

I make this statement mindful of what Martin Luther King Jr. said in this same ceremony years ago: "Violence never brings permanent peace. It solves no social problem: it merely creates new and more complicated ones." As someone who stands here as a direct consequence of Dr. King's life work, I am living testimony to the moral force of non-violence. I know there's nothing weak -- nothing passive -- nothing naïve -- in the creed and lives of Gandhi and King.

But as a head of state sworn to protect and defend my nation, I cannot be guided by their examples alone. I face the world as it is, and cannot stand idle in the face of threats to the American people. For make no mistake: Evil does exist in the world. A non-violent movement could not have halted Hitler's armies. Negotiations cannot convince al Qaeda's leaders to lay down their arms. To say that force may sometimes be necessary is not a call to cynicism -- it is a recognition of history; the imperfections of man and the limits of reason.

- We must begin by acknowledging the hard truth: We will not eradicate violent conflict in our lifetimes. There will be times when nations -- acting individually or in concert -- will find the use of force not only necessary but morally justified.

Bottom of the 10th

I still can't decide if the second half of Ken Burns's “Tenth Inning” doc, about the 2000s, made up for some of the problems in the first half, about the 1990s, or if, because the aughts corrected some of the '90s excesses (performance enhancing drugs; Yankees world championships), such a turnaround is inevitable.

What Burns does works. But he's still presenting the narrative of the time (“Wow, look at all these homeruns!”) with only a bit of foreshadowing (psst: chemicals may be involved). John Thorn still says with a straight face: “You can forget about the debate... the greatest pitcher in the history of baseball is Roger Clemens.” Tom Veducci still says of Barry Bonds: “This is the most feared hitter who ever lived.” The metaphor I brought up last time still works. It's as if Burns is reveling in the Cincinnati Reds amazing upset over the Chicago White Sox in the 1919 World Series before coughing and adding the historical perspective: “Oh, by the way: the Sox were paid to lose.”

None of the talking heads are angry enough about steroids, either. The record books are meaningless now. Trust in the game is  meaningless. There's a discussion at the end about the asterisk next to Bonds' homerun record, the career one, 762 homeruns, and most of the talking heads—not wishing to sound like Ford Frick on Roger Maris—say of course not, no asterisk, before adding that, yes, there is a metaphoric one. “The asterisk is whatever exists in the minds of fans,” Dan Okrent says (dismissively?). Yes, it is. But it's not just with Bonds' record; it's with the entire era. The last 20 years of baseball has an asterisk. What's legitimate and what isn't? What counts and what doesn't? Albert Pujols has the best first five seasons of any player ever. Is he juiced? Jose Bautista, this year, at the age of 29, hits 54 homeruns, when his career-best had been 16. Do alarm bells go off? Did anyone in the pre-steroid era make such a leap? The tragedy isn't Barry Bonds, it's all of baseball. Everything is tainted. And the taint ain't over.

meaningless. There's a discussion at the end about the asterisk next to Bonds' homerun record, the career one, 762 homeruns, and most of the talking heads—not wishing to sound like Ford Frick on Roger Maris—say of course not, no asterisk, before adding that, yes, there is a metaphoric one. “The asterisk is whatever exists in the minds of fans,” Dan Okrent says (dismissively?). Yes, it is. But it's not just with Bonds' record; it's with the entire era. The last 20 years of baseball has an asterisk. What's legitimate and what isn't? What counts and what doesn't? Albert Pujols has the best first five seasons of any player ever. Is he juiced? Jose Bautista, this year, at the age of 29, hits 54 homeruns, when his career-best had been 16. Do alarm bells go off? Did anyone in the pre-steroid era make such a leap? The tragedy isn't Barry Bonds, it's all of baseball. Everything is tainted. And the taint ain't over.

For a time I thought Burns's narrative should've focused on the great players who didn't partake (Ken Griffey, Jr.; Frank Thomas), and who were subsequently overshadowed by those who did (McGwire, Sosa, Bonds, A-Rod), but of course we're back to the impossibility of proving a negative. We don't know that Griffey and Thomas didn't partake; we just assume it from their career trajectories.

But if they didn't, isn't that the tragedy? The overshadowing of the legitimate by the illegitimate? The doc says the inflated players were a reflection of the inflated times (stock market; housing market) and excuses them. That's a cop-out. Baseball should not reflect the worst of our society; it should be an oasis from the worst in our society.

Other problems:

- The hyperbole: Pedro Martinez “made himself into one of the greatest players the game had ever seen.” Mariano Rivera became “the most successful closer of all time.” Randy Johnson was “the most feared left-hander of all time.” The Yankees were led by Derek Jeter, “one of the most popular and respected players in baseball history.” It's not that I don't agree with some of these statements; it's that they're a) hard to prove (and thus meaningless), and, b) a bit much when strung together. It feels like lazy writing.

RJ: feared. Pedro: great. Jeter: respected.

- Turning the New York Yankees into underdogs: Here's Tom Boswell on the 2001 World Series: “Johnson and Schilling are more dominant now than anyone in the history of baseball. And that's what the Yankees are up against.” I suppose this could go under hyperbole, too. (More dominant than Koufax/Drysdale?) But it's worse than the average hyperbolic statement because it's turning a team that has won three World Championships in a row, and 26 overall, and has the highest payroll in baseball, into the underdog.

- Turning the New York Yankees into “America's team”: Voiceover on the 2001 World Series: “The New York Yankees, the team much of America was rooting for, had lost.” Another narrative of the time that I didn't buy at the time and don't buy now. Where's the evidence? Maybe among the general population, maybe among non-baseball fans—the kind of people who only know from Willie Mays and Derek Jeter—sure, why not? Post-9/11, with all the NYPD caps and NYFD caps and shots of Rudy G. sitting in the stands, the Yankees were probably less hated than normal. But among baseball fans? Who had just suffered through three years of Yankee celebrations and 26 in all? Who suffered through Yankee fans talking up rings as if they owned them? I remember bottom of the ninth in Game 7 when Mark Grace led off with a single and David Delucci pinch-ran for him and then Damian Miller laid down a fat bunt in front of Rivera who opted to go for the force at second. Delucci came in hard, safe, and Jeter, covering the bag, grabbed his ankle, which was already injured. And I got up close to my TV set and yelled, “Writhe, Jeter, writhe!” Admittedly I'm a special case. But America's team? Only in the way that Goldman Sachs is American's investment bank: big and bloated and known and despised.

- Turning the spectacular losses of the New York Yankees into tragic events: Burns did this in his original doc with the 1960 World Series. Bill Mazeroski hits one of the most famous homeruns ever hit and who do we hear from? The Pirates and their fans? No. We hear from the Yankees and their fans. Billy Crystal: “I still hurt,” etc. Same here. On 2001, do we hear from the Diamondbacks and their fans about this improbable, beautiful, spectacular, bottom-of-the-ninth-inning victory over Mariano Rivera and the New York Yankees? Nope. Cue Billie Holliday's “God Bless the Child” and cut to Joe Torre saying, “That night was about as sad as it gets.” Oh, boo hoo, motherfucker. Just four rings in your pocket instead of five. If Ken Burns, a supposed Red Sox fan, doesn't realize that every Yankees loss is a moment for celebration then he shouldn't be baseball's documentarian. I mean: Billie Holliday? The song's about poverty, Ken. God bless the child that's got a $200 million payroll.

- VORP? OPS? One of the biggest stories of the 2000s was the acceptance, after decades of knocking at the baseball door, of Bill Jamesian stats, by Oakland GM Billy Beane and others, which helped transform the game. It's part of the reason why the Yankees stopped winning and the Red Sox started; and it's part of the reason why the Yankees began to win again. Brian Cashman did his work. He read Moneyball and changed his ways. So why not an interview with Bill James, Rob Neyer, Michael Lewis? Why not Billy Beane or Theo Epstein or Brian Cashman? Instead we get Jon Miller channeling Sid Dithers. Vas you talkin' to me? It's like Ron Paul explaining why big government is necessary.

- “The popularity of the sport is just enormous.” This is Commissioner Bud Selig, one of Burns's talking heads, trotting out his company line. And measured by attendance, sure, there's some truth in it, but that's only because baseball has been turned into a family event. The appeal is as much the mascot and the fireworks and the various races (hydro/presidents/sausages) as the game itself. Maybe it's more than the game itself. The answer to his comment is in World Series ratings, which drop and keep dropping, in a way that, even in this fragmented, internetted age, the ratings for the Super Bowl don't. The Super Bowl is still central to our culture. The World Series isn't. In baseball, fans root for their team but not for the game, and that's part of the problem. Maybe that's the whole problem.

- “Bonds hits it high! He hits it DEEP! It is...outta here!” I didn't need to hear this as often as I heard it.

But the doc got right that dispiriting, record-breaking 756th homerun. “The whole thing was a joyless march toward the inevitable,” Bob Costas says. “Baseball powerless. Selig with his hands in his pockets...”

It was smart tapping ESPN's editorial director Gary Hoenig as a talking head. He had great comments throughout but my favorite was on Mark McGwire's testimony before U.S. Congress: “And you could just see him deflate like a giant balloon in a Thanksgiving Day parade...”

And it got right the sheer, magical joy of the Red Sox thumping the Yankees in the 2004 ALCS. “It was,” announcer Keith David intoned, “the greatest comeback in baseball history.”

And for once, that wasn't hyperbole.

'Invisible Bridge' Author Rick Perlstein on 'Rocky,' 'Roots,' and Whether Reaganism Needed Reagan

A few weeks ago I Skyped an interview with Rick Perlstein, author of a series of acclaimed books on the rise of the far right in America: “Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and The Unmaking of the American Consensus,” “Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America,” and now “The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan.” You can see video of the interview here. What follows is the transcript of that interview, edited and condensed.

Q: Two threads seem to work their way through “The Invisible Bridge.“ One is how the various crises of the 1970s—Vietnam, Watergate, oil—give us the opportunity to reckon with the less palatable aspects of our history, and to mature, hopefully. The other is the rise of Ronald Reagan, who, for his entire life, did the opposite: reduced moral complexity to moral simplicity. So do we blame Reagan for blunting this opportunity for us as a country to mature?

Perlstein: Well, you know Erik, they make me put those Presidents on the cover of the books because they sell. The books are really about us, the electorate. I’m interested in why we choose these people. Why we rescue them from obscurity and turned them into our leaders. I’m really influenced by John MacGregor Burns, the late political scientist. He wrote this big book called “Leadership,” and it’s basically a whole book about how leaders emerge when these powerfully charismatic people match the unconscious longings of a national public.

So it’s not just Reagan. The book is about a confrontation between those two ways of thinking about America. Throughout, there’s this debate going on between the people who are saying, “Look, we need to change course and think about America’s role in the world in a different way,” and the people who are saying, “America’s the best country in the world, and always has been and always will be.” Even if Reagan had never been born, we still would’ve had, for example Gerald Ford a few months after the fall of Saigon, drumming up this “Remember the Maine” fake patriotic event of the Mayaguez—where he sends out a military mission to supposedly rescue these merchant seaman who didn’t need rescuing. He sends in B-52s and a Normandy-style invasion of some North Vietnamese island beach that ends up killing more American serviceman than the supposed merchant seaman they rescued. And he suddenly finds himself hailed as the new Caesar. Magazine covers are saying “America’s got its mojo back.”

It’s not just Reagan. It’s us.

Q: One reason I find this book particularly fascinating is that it mirrors in politics what I’ve observed in the movie industry. From about 1967 to 1977, our most popular movies were fairly morally complex. “The Godfather” was the No. 1 movie in 1972. “One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest was the No. 2 movie of 1975. Adjust for inflation, and it grossed around $450 million.

Perlstein: I wish I had known that a few years ago, Erik.

Q: And it’s about a bunch of guys in a mental institution who rebel against...

Perlstein: Authority.

Q: Exactly. If it were made today it would get a limited release in New York, and LA.

Perlstein: Then comes “Jaws,” and then comes “Star Wars.”

Q: Well, “Rocky” was, I guess, the invisible bridge between those two. For awhile, we didn’t need the Hollywood ending in movies. “Rocky” began that change.

Perlstein: Right. It was all the sentiment that the public [at the time] could credibly stomach. He couldn’t win at the end—that was just too much.

Q: So he went the distance. The first half almost looks like a 1970s movie. Very gritty. A down-and-out guy with mob connections; then it just turns into the feel-good story we all know.

Perlstein: Do you know Jefferson Cowie’s book “Staying Alive”? You’ll enjoy that a great deal. It’s a history of the working class in the ‘70s but brilliant stuff on “Rocky,” which was based on a real guy, Chuck Wepner. I didn’t write about it, but I will in the next book. The racial politics are fascinating because it was Don King basically saying, “Let’s give them a chance.” So he rescues this club fighter from Philadelphia, Chuck Wepner, from obscurity, sets him up as a sparring partner for Ali, and he goes the distance. Sylvester Stallone watched the Wepner fight on close-circuit TV, and in an amphetamine-fueled binge wrote the screenplay in like six straight hours. It was based on Wepner and the racial politics of the ‘70s—in which white guys were suddenly seeing themselves as objects of pity.

The great (sshhh) white hope.

Q: Eddie Murphy does great stuff on that in his comedy routines in the ‘80s.

Perlstein: Do you remember the jokes?

Q: Basically they're about the Italian guy at the movie theater who carries the “Rocky” fantasy out into the lobby.

Perlstein: For my next book I’ll have to figure out a way to work it in. I believe I recall reading somewhere that white guys hopped up on Rocky were committing hate crimes. And in the same way ... I remember sitting in the basement of the Renaissance bookstore in Milwaukee when I was 16 and reading Time magazine, and learning that when “Roots” came out, white kids were beating up black kids because they saw it as degraded slaves and black kids were beating up white kids because they saw them as sadistic masters. I’m fascinated by these kinds of divisions.

But the real story in “Roots”—that’s salient for my work—is you would think it would’ve inspired this great reckoning with America’s moral past. The same way Vietnam would inspire a reckoning with America being a policeman of the world and Watergate would inspire this reckoning with our reverence for our leaders. No. What it inspired was this genealogy fad in which white people wanted to do what Alex Haley did. There’s a whole book about it by this Harvard professor called “Roots, Too.” It’s like, “We have roots too!” It was in a way very reactionary. People tried to locate their own oppressed pasts, so they could claim the moral status as victims too. That’s a very Reagan movement.

Q: So I suppose the question isn’t why we returned to moral simplicity in the mid-’70s, but how we got interested in moral complexity in the first place.

Perlstein: That kind of goes unexamined in the book, but I think this was a product of the ‘60s generation. When I talk about the ‘60s generally, this gets into a paradox. We were the most prosperous society in history—you could burn down a building one day and show up in a suit for a job at IBM the next—because there was so much work and so much prosperity. So I think people had the confidence to be able to think about these kinds of difficult questions.

But the paradox is, by the ‘70s, even that prosperity dribbles away, and you just begin to see this very dark reckoning with broken institutions. It’s like here’s this very American pastime of driving your giant car as far as it’ll go and suddenly the price of fuel quadruples because of the inscrutable actions of oil sheiks 10,000 miles away. People didn’t even think of petroleum as a commodity. It was just there, like the air and the water.

Q: Right. And scary. If you’d told me back then that gas would still be available and relatively cheap in 2014, I wouldn’t have believed you.

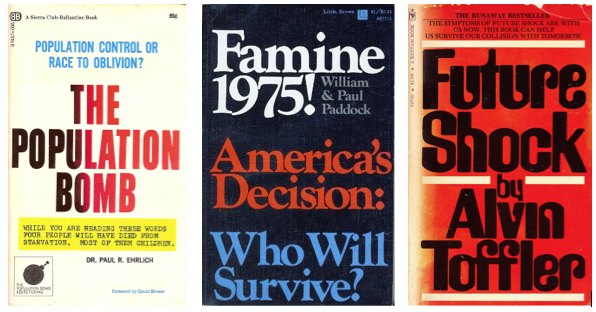

Perlstein: Right. A lot of the success of Reaganism drafted on the exaggeration of the apocalyptic fears: we’re going to be eating leaves and grass and nuts and berries. One of the inanities of George Will as a climate change denier is that he’s able to go up on TV every week, on ABC, and say “Well in the ‘70s they were worried about global cooling.” Well, in the 70s they were worried about everything. You could write a book about any kind of apocalyptic theory and get a reasonable audience.

'70s books: We've seen the future and it sucks.

Q: What’s your methodology in researching and writing these books? Do you just focus on a particular subject, like Patty Hearst, and read as much as you can about her?

Perlstein: It’s divided into two things. One is, yes, I know the big signposts and themes, like Patty Hearst, and research them in very specific ways: books, videos, films, whatever. But the other is very improvisational. I try to consume the kind of media that people in the time would consume. A lot of it is a stratified sample, right? It’s like I can’t read every newspaper every day. But, for example, doing my research now, I’ll do a search in a newspaper database for any time Ronald Reagan was mentioned in an article in 1977. When you do that you get a pretty good sample of all sorts of political articles. That helps fill in what the narrative is.

Of course, I do have to learn things that are completely unexpected.

In the case of articles about Ronald Reagan in 1976 and 1977, of course there’s the issue of age. Is he going to run for President or is he too old? But he’s obviously making a bid for leadership of the Republican Party; and the first thing he has to do is deny that it’s his fault that Ford lost. It turns out that he basically boycotted campaigning for the Republican ticket in 1976. Whenever he gave a speech, he would almost never mention Ford, but he would mention the great Republican platform. Of course, the Republican platform was one that his followers forced on the party. So there are all sorts of fascinating politics around that.

Suddenly the storyline fills itself out. The first thing Reagan has to do is re-establish his credibility as a good Republican. That takes me in a direction. Suddenly I have the beginnings of an outline. History is about chronology—one thing follows another and there’s cause and effect—and tracing out those lines of causality, that’s how the content builds out to form, and the form is indicative of the content.

Q: As for consuming the media that we consumed at that time: Can you do that today and write the kinds of books you write, or are we too fragmented as a society? Back then we had national meeting places. We all visited with Walter Cronkite. Today? Not so much.

Perlstein: Well, it’s organized pretty nicely, right? It’s all automated. The proliferation of media can be very deceiving: Are there a million stories out there, or just there are a million versions of the same story? We had a pretty effective top-down propaganda campaign that got us into the war in Iraq. It didn’t seem like any of the powers-that-be had any trouble just instantiating into the mainstream of American thought a very specific narrative that they were able to get across as if they were doing it with just three networks and a few big newspapers. It’s not as if the kind of collective hive mind of America is going in truly different directions. There’s still some very solid common directions. There’s still patterns of commonality.

Q: And organizing forces.

Perlstein: Organizing forces, that’s right. So I’m not as dubious about that. I think that historians will have the creativity to turn this massive material into a shape, because it does have a shape. American society does have a direction and a valence. I look at the coral reef. I mean, yes it has a zillion different organisms on it, but obviously they’re not all heading in different directions. They’re creating a structure.

Q: How do you keep up with what’s going on in the world as you are writing about what’s happened in the past?

Perlstein: I’m not really a news junkie. I listen to NPR in the morning and I have a very few favorite blogs that I follow. I get The New Yorker, and they pile up in a corner like with everyone else; I get The New York Review of Books and they pile up in a corner. I listen to what people are saying. Henry James said a writer is someone on whom nothing is lost. So I just try and pay attention.

Q: Isn’t it odd how much this history, which goes back 50 years, includes the same arguments we’re having today?

Perlstein: Fifty years isn’t that long. If you think about the arguments people were having between 1870 and 1920, they were similar arguments: about how labor is going to work, and how machines are going to affect our lives.

Q: But it is interesting that in “The Invisible Bridge” you write about the textbook wars in West Virginia and now we’re having the same thing in Colorado. Except back then the conservative forces were outside protesting the liberal insiders. Now some of them ...

Perlstein: They managed to get a three-to-two majority on the board. Canal County had a five-person board and one conservative. The county in Colorado, Jefferson County, has a five-person board and they have three conservatives. That margin changes the politics. I guess, in a way, the history I’m telling you is how it turned from one conservative member and four liberal members to three conservative members and two liberal members.

Q: You’ve been attacked by the right for your portrayal of Ronald Reagan—you even got swift-boated, in a certain sense—but in a way you’re tougher on the Democrats.

Perlstein: I think that one of the big stories I’m telling is about how the Democrats have retreated from the New Deal tradition. That becomes very salient in the 1974 Watergate baby election, in which the most charismatic figure, Gary Hart, literally says that he’s opposed to the New Deal tradition. That’s a historical tragedy because this was just at the time in which 1920s-style inequality is beginning to ramp itself up. The one politician who seems to be talking about this and thinking about this, Hubert Humphrey, is seen as an embarrassment because he supported the Vietnam war, and he hangs out with all these unfashionable, blue-collar hard hat types.

Everyone remembers that in 1995 Bill Clinton gave us the “Age of big government is over” State of the Union address. People were talking about it like he was inventing something new, but Carter’s State of the Union address in 1978 was almost identical. The fact that Democrats are never going to get credit for moderation—they’ll always be the extremist, liberal party—is an important political lesson for us in the present. They might as well move left, because they’re going to get blamed for moving left whether they do or not.

HHH statue in downtown Minneapolis. The last of the hard-hat Democrats?

Q: So if Reagan had won the GOP nomination in ‘76, do you think he would have won the general election?

Perlstein: I think it was just a Democratic year. I think he probably would’ve lost the presidency and his political career might have been over. Then again, the Republicans have a history of nominating the next in line, and people get two bites of the apple. Certainly Richard Nixon did. So maybe things would’ve been exactly the same.

As I begin to look into the 1980 Republican nomination fight—this came as a surprise to me—basically all the candidates except for John Anderson were running as conservatives: George Bush, John Connally, Reagan. So I think Reaganism was a direction the country was going in whether Reagan was the guiding genius or not.

Q: How long do you keep doing this history? Are you going to end with Reagan’s victory in 1980?

Perlstein: His inauguration, because I find the period between his election and his inauguration really fascinating as people jockey for possession of Reagan’s mind. Then I’ll do something else. I don’t know what. Watch this space.

”It's not just Reagan. It's us."