Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

Whatever Happened to the American Epic?

With the roll-out of “Australia,” the big-budget epic starring two Australians (Hugh Jackman, Nicole Kidman), directed by an Australian (Baz Luhrman), and produced and distributed by a company owned by an Australian (Fox/Rupert Murdoch), the myopic, possibly xenophobic question that arises is: Whatever happened to the American epic? And which are the best American epics?

The first question is the easier one. These days, the longer the movie the less likely it’ll be made. Longer means fewer viewings, which means less box office, particularly opening weekend, and opening weekend is the whole game now.

Then there are the historical reasons. Most of the great American battles of the 20th century have been abroad (World Wars I and II, particularly), while the battles at home, regarding race, class and politics, are still divisive enough to turn away the moneymen who run Hollywood. Put it this way: the great internal American battle of the 20th century, the civil rights movement, despite having an obvious victor in both moral and legislative terms, remains virtually unrepresented in a theatrical release, and when it is—say, “Mississippi Burning”—it stars white people, with black people relegated to supporting, suffering roles. The fact that no theatrical release has ever starred anyone as Martin Luther King, Jr. is a rather stunning achievement for an industry daily castigated as liberal.

Put bluntly, we no longer agree on our national story, and the studios are rarely the type to go once more (or even once) into the breach.

Last June, in fact, the American Film Institute trotted out its list of the top 10 films in various genres, including epics, and most of these epics were about Europeans (“Lawrence of Arabia”; “Schindler’s List”) or Romans (“Ben-Hur”) or set in Biblical times (“The Ten Commadments”). Some involved Americans (“Saving Private Ryan”; “Titanic”), but only one of the ten was about Americans and set in America: “Gone with the Wind” at no. 4.

So if this is our definition of “American” (“about”; “set in”), and if our definition of “epic” involves something grand, often romantic and nostalgic, certainly long (at least 150 minutes of screentime and 5-10 years of character time), and set in the past with a hard-to-define “sweeping” element, the question remains: What are the great American epics?

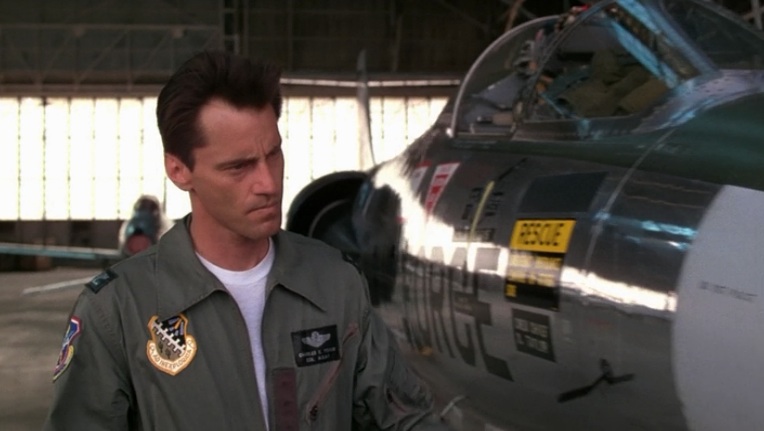

Chuck Yeager (Sam Shepard) thinks about busting new frontiers in “The Right Stuff”.

Here’s a list. Your results may vary.

5. Dances with Wolves (1990)

“Lawrence of Arabia” topped AFI’s list of great epics, and, in terms of story (if not greatness), “Dances” is an American “Lawrence”: the rebellious white man going native. Lt. Dunbar essentially dies during the Civil War and is resurrected, slowly, as Dances with Wolves.

Costner probably overdoes the irony—the naked white man greeting the “savage”—and for many he overdoes the nobility of this tribe, particularly as compared with the mendaciousness and wastefulness of whites. At the same time, this is one of the most well-rounded portraits of a Native American tribe. The Sioux here joke, tease, go to war, scalp white hunters and celebrate the scalping. We’re still required a white guide (as opposed to the African-American and Italian stories, below), but this gives the film its true drama: the tension between cultures that have never met.

4. Malcolm X (1992)

“The Autobiography of Malcolm X” appealed to a young Barack Obama because, as he writes in “Dreams From My Father,” Malcolm’s “repeated acts of self-creation spoke to me.”

One could argue that, at least in Spike Lee’s epic, Malcolm is less creator than created. He simply switches mentors. His life, in fact, divides neatly into two acts. In the first, after following mentors Shorty and West Indian Archie, he runs from Archie’s guns and leads a life of drugs and crime as the head of his own gang. He winds up in prison. In the second act, after following mentors Brother Baines and Elijah Muhammad, he runs from the Nation of Islam’s guns and leads a life of both black nationalism and international brotherhood as the head of his own ministry. He winds up assassinated.

The most powerful of his conversions is the one in prison. Malcolm’s knowing hustler smile runs into the blank wall of Brother Baines’ certitude until, forced to question why he straightens his hair, and why black is always negative and white is always positive, his knowingness crumbles and he admits he doesn’t even know his own name.

It’s a powerful film telling a powerful story—a wholly American story. How’s that for irony? That someone who hated America for most of his public life is representative of it. This country, after all, is in a perpetual act of self-creation, and, in case you weren’t paying attention, we just switched mentors.

3. The Right Stuff (1983)

True, most epics are nostalgic and this one’s cynical—cynical about the way heroes are sold to the public—but it doesn’t mean the men who are sold, the seven Mercury astronauts, aren’t heroes. It’s the process the movie is cynical about. And if these seven men don’t quite have the right stuff of the original hero, Chuck Yeager (Sam Shepherd)—who broke the speed of sound to no media attention in 1947, and about whom the movie is nostalgic, because he represents a time before the process mucked things up, when you did the thing just for the doing of it—well, the original astronauts still had some pretty good stuff.

The brunt of the movie is part of another all-American tradition. It’s about the creation of a team. Sure, we can be cynical or amused about why the team was created in the first place, and the fact that, originally, officials in the U.S. government were thinking about using trapeze artists or surfers as astronauts and only focused on test pilots at Ike’s insistence. We can be cynical that the powers-that-be, or at least their grubby little surrogates, didn’t even recognize the right stuff when they saw it, rejecting Yeager out of hand because “he doesn’t fit the profile.” It’s also true that the seven men arrived with their separate loyalties—Air Force, Navy, Marine Corps—and with different versions of morality. (Ed Harris’ John Glenn is the All-American boy scout and Dennis Quaid’s Gordon Cooper is the All-American hot dog.) But they come together. Through adversity—treated like lab specimens; momentarily replaced by chimps—they become a team. Hell, they become a family. When a tech at mission control worries over a sound as John Glenn tries to re-enter earth’s atmosphere, Alan Shepherd (Scott Glenn), mollifies his concerns. “It’s humming,” he says wistfully. “It’s him. It’s alright, he does that.” He’s almost a spouse here.

Two missteps. The magic realism of aboriginal sparks leading to space fireflies is a bit silly—almost worthy of Oliver Stone’s American Indian fixation—while the movie ends in the wrong place. It gives us, with a nostalgic, heroic flourish, Gordo Cooper going into space. It should’ve ended with Yeager walking away from the plane crash. “Is that a man?” Yep, that’s a man.

2. Gone with the Wind (1939)

The most popular movie of all time (adjusted for inflation) is a story between a bitch and a bastard in which the abolition of slavery is mourned. “Here in this pretty world,” the beginning titles tell us, “Gallantry took its last bow. Here was the last to be seen of Knights and their Ladies Fair, of Master and of Slave...”

Yet somehow it still works. Maybe because, despite the abundance of dashing silhouettes against red skies, the movie is too smart to believe in such romance. Knights? “All we’ve got is cotton and slaves and...arrogance,” Rhett famously tells the southern men hot for war. Ladies Fair? Scarlett is a spoiled, pouting thing who craves what she can’t have because she can’t have it, and upends lives, including her own, to get it. She twice marries the wrong man, and when she marries the right one, Rhett, she doesn’t realize it until he’s halfway out the door. The nightmare she has on her honeymoon, the thing disappearing into the fog, which we originally think is Tara, turns out to be Rhett, who doesn’t give a damn.

Why is such an awful character keep appealing to us? Here’s a clue: Scarlett has more personality in one raised eyebrow than most modern female characters have in their entire bodies.

1. The Godfather – Parts I and II (1972-74)

This usually gets dumped into the gangster genre but there is no better example of the American epic than these two films. They take us from the small-pox isolation of a small Italian boy, Vito Corleone, on Ellis Island in 1901, staring out behind iron bars at the ultimate symbol of American liberty, to that boy’s youngest son, Michael, nearly 60 years later, wealthy and powerful beyond Vito’s imagination, but just as isolated and gated in his Nevada compound.

If the tragedy of the first film is that Michael becomes his father (he becomes Godfather), the tragedy of the second film is that Michael isn’t enough like his father. Vito, from nothing, and with great dignity and respect, creates a family-run empire. Michael expands and consolidates the empire but in the process loses his family. “I don’t have to wipe everyone out, Tom,” Michael says. “Just my enemies.” But you can tell from his eyes, which get darker and deader as the films progress, that everyone is becoming his enemy. He kills to protect, but he’s killing what he should protect. Bye-bye Fredo.

Did it have to wind up this way? Vito traveled west to New York but carried something with him the entire time. Michael traveled west to Nevada but lost something in the process—if he ever had it.

—The conversation on what makes an American epic, and why movies like “Giant,” “Ragtime" and “How the West Was Won” didn't make the top 5, is continued, with a cast of thousands, on the blog. This article was originally published on 11/25/08 on MSNBC.com.